In the last few decades there has been an enormous shift in the capitalist economy in the direction of the globalization of production. Much of the increase in manufacturing and even services production that would have formerly taken place in the global North—as well as a portion of the North’s preexisting production—is now being offshored to the global South, where it is feeding the rapid industrialization of a handful of emerging economies. It is customary to see this shift as arising from the economic crisis of 1974–75 and the rise of neoliberalism—or as erupting in the 1980s and after, with the huge increase in the global capitalist labor force resulting from the integration of Eastern Europe and China into the world economy. Yet, the foundations of production on a global scale, we will argue, were laid in the 1950s and 1960s, and were already depicted in the work of Stephen Hymer, the foremost theorist of the multinational corporation, who died in 1974.

For Hymer multinational corporations evolved out of the monopolistic (or oligopolistic) structure of modern industry in which the typical firm was a giant corporation controlling a substantial share of a given market or industry. At a certain point in their development (and in the development of the system) these giant corporations, headquartered in the rich economies, expanded abroad, seeking monopolistic advantages—as well as easier access to raw materials and local markets—through ownership and control of foreign subsidiaries. Such firms internalized within their own structure of corporate planning the international division of labor for their products. “Multinational corporations,” Hymer observed, “are a substitute for the market as a method of organizing international exchange.” They led inexorably to the internationalization of production and the formation of a system of “international oligopoly” that would increasingly dominate the world economy.1

In his last article, “International Politics and International Economics: A Radical Approach,” published posthumously in 1975, Hymer focused on the issue of the enormous “latent surplus-population” or reserve army of labor in both the backward areas of the developed economies and in the underdeveloped countries, “which could be broken down to form a constantly flowing surplus population to work at the bottom of the ladder.” Following Marx, Hymer insisted that, “accumulation of capital is, therefore, increase of the proletariat.” The vast “external reserve army” in the third world, supplementing the “internal reserve army” within the developed capitalist countries, constituted the real material basis on which multinational capital was able to internationalize production—creating a continual movement of surplus population into the labor force, and weakening labor globally through a process of “divide and rule.”2

A close consideration of Hymer’s work thus serves to clarify the essential point that “the great global job shift”3 from North to South, which has become such a central issue in our time, is not to be seen so much in terms of international competition, deindustrialization, economic crisis, new communication technologies—or even such general phenomena as globalization and financialization—though each of these can be said to have played a part. Rather, this shift is to be viewed as the result primarily of the internationalization of monopoly capital, arising from the global spread of multinational corporations and the concentration and centralization of production on a world scale. Moreover, it is tied to a whole system of polarization of wages (as well as wealth and poverty) on a world scale, which has its basis in the global reserve army of labor.

The international oligopolies that increasingly dominate the world economy avoid genuine price competition, colluding instead in the area of price. For example, Ford and Toyota and the other leading auto firms do not try to undersell each other in the prices of their final products—since to do so would unleash a destructive price war that would reduce the profits of all of these firms. With price competition—the primary form of competition in economic theory—for the most part banned, the two main forms of competition that remain in a mature market or industry are: (1) competition for low cost position, entailing reductions in prime production (labor and raw material) costs, and (2) what is known as “monopolistic competition,” that is, oligopolistic rivalry directed at marketing or the sales effort.4

In terms of international production it is important to understand that the giant firms constantly strive for the lowest possible costs globally in order to expand their profit margins and reinforce their degree of monopoly within a given industry. This arises from the very nature of oligopolistic rivalry. As Michael E. Porter of Harvard Business School wrote in his Competitive Strategy in 1980:

Having a low-cost position yields the firm above-average returns in its industry…. Its cost position gives the firm a defense against rivalry from competitors, because its lower costs mean that it can still earn returns after its competitors have competed away their profits through rivalry…. Low cost provides a defense against powerful suppliers by providing more flexibility to cope with input cost increases. The factors that lead to a low cost-position usually also provide substantial entry barriers in terms of scale economies or cost advantages.5

This continuous search for low-cost position and higher profit margins led, beginning with the expansion of foreign direct investment in the 1960s, to the “offshoring” of a considerable portion of production. This, however, required the successful tapping of huge potential pools of labor in the third world to create a vast low-wage workforce. The expansion of the global labor force available to capital in recent decades has occurred mainly as a result of two factors: (1) the depeasantization of a large portion of the global periphery by means of agribusiness—removing peasants from the land, with the resulting expansion of the population of urban slums; and (2) the integration of the workforce of the former “actually existing socialist” countries into the world capitalist economy. Between 1980 and 2007 the global labor force, according to the International Labor Organisation (ILO), grew from 1.9 billion to 3.1 billion, a rise of 63 percent—with 73 percent of the labor force located in the developing world, and 40 percent in China and India alone.6

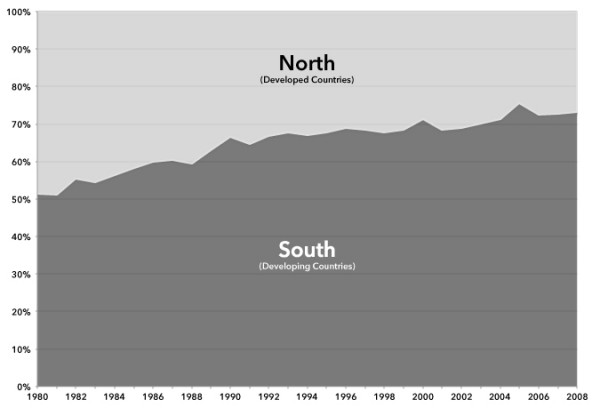

The change in the share of “developing countries” (referred to here as the global South, although it includes some Eastern European nations), in world industrial employment, in relation to “developed countries” (the global North) can be seen in Chart 1. It shows that the South’s share of industrial employment has risen dramatically from 51 percent in 1980 to 73 percent in 2008. Developing country imports as a proportion of the total imports of the United States more than quadrupled in the last half of the twentieth century.7

Chart 1. Distribution of Industrial Employment, 1980–2008

Notes: “Industrial employment” is a broad category that includes mining, manufacturing, utilities (electricity, gas, and water supply), and construction. From 2003 to 2007, manufacturing and mining averaged 58.1 percent of total industrial employment in the United States, while in China the ratio was 75.2 percent (see “Table 4b. Employment by 1-digit sector level [ISIC-Rev.3, 1990]”). Based on the two largest economies, therefore, the broad category of “industrial employment” systematically understates the extent to which the world share of manufacturing has grown in developing countries. Classification of countries as “developing” (South) and “developed” (North) is taken from UNCTAD. The sample averaged 83 countries over the entire period and there were breaks in the country-level series depending on ILO data availability. For example, data were only available for India in 2000 and 2005, and this explains the spikes in these two years.

Sources: ILO, “Key Indicators of the Labour Market (KILM), Sixth Edition,” Software Package (Geneva: International Labour Organization, 2009); UNCTAD, “Countries, Economic groupings,” UNCTAD Statistical Databases Online, http://unctadstat.unctad.org (Geneva: Switzerland, 2011), generated June 28, 2011.

The result of these global megatrends is the peculiar structure of the world economy that we find today, with corporate control and profits concentrated at the top, while the global labor force at the bottom is confronted with abysmally low wages and a chronic insufficiency of productive employment. Stagnation in the mature economies and the resulting financialization of accumulation have only intensified these tendencies by helping to drive what Stephen Roach of Morgan Stanley dubbed “global labor arbitrage,” i.e., the system of economic rewards derived from exploiting the international wage hierarchy, resulting in outsized returns for corporations and investors.8

Our argument here is that the key to understanding these changes in the imperialist system (beyond the analysis of the multinational corporation itself, which we have discussed elsewhere)9 is to be found in the growth of the global reserve army—as Hymer was among the first to realize. Not only has the growth of the global capitalist labor force (including the available reserve army) radically altered the position of third world labor, it also has had an effect on labor in the rich economies, where wage levels are stagnant or declining for this and other reasons. Everywhere multinational corporations have been able to apply a divide and rule policy, altering the relative positions of capital and labor worldwide.

Mainstream economics is not of much help in analyzing these changes. In line with the Panglossian view of globalization advanced by New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, most orthodox economists see the growth of the global labor force, the North-South shift in jobs, and the expansion of international low-wage competition as simply reflecting an increasingly “flat world” in which economic differences (advantages/disadvantages) between nations are disappearing.10 As Paul Krugman, representing the stance of orthodox economics, has declared: “If policy makers and intellectuals think it is important to emphasize the adverse effects of low-wage competition [for developed countries and the global economy], then it is at least equally important for economists and business leaders to tell them they are wrong.” Krugman’s mistaken reasoning here is based on the assumption that wages will invariably adjust to productivity growth, and the inevitable result will be a new world-economic equilibrium.11 All is for the best in the best of all capitalist worlds. Indeed, if there are worries in the orthodox economic camp in this respect, they have to do, as we shall see, with concerns about how long the huge gains derived from global labor arbitrage can be maintained.12

In sharp contrast, we shall develop an approach emphasizing that behind the phenomenon of global labor arbitrage lies a new global phase in the development of Marx’s “absolute general law of capitalist accumulation,” according to which:

The greater the social wealth, the functioning capital, the extent and energy of its growth, and therefore also the greater the absolute mass of the proletariat and the productivity of its labour, the greater is the industrial reserve army…. But the greater this reserve army in proportion to the active labour-army, the greater is the mass of a consolidated surplus population, whose misery is in inverse ratio to the amount of torture it has to undergo in the form of labour. The more extensive, finally, the pauperized sections of the working class and the industrial reserve army, the greater is official pauperism. This is the absolute general law of capitalist accumulation.13

“Nowadays…the field of action of this ‘law,’” as Harry Magdoff and Paul Sweezy stated in 1986,

is the entire global capitalist system, and its most spectacular manifestations are in the third world where unemployment rates range up to 50 percent and destitution, hunger, and starvation are increasingly endemic. But the advanced capitalist nations are by no means immune to its operation: more than 30 million men and women, in excess of 10 percent of the available labor force, are unemployed in the OECD countries; and in the United States itself, the richest of them all, officially defined poverty rates are rising even in a period of cyclical upswing.14

The new imperialism of the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries is thus characterized, at the top of the world system, by the domination of monopoly-finance capital, and, at the bottom, by the emergence of a massive global reserve army of labor. The result of this immense polarization, is an augmentation of the “imperialist rent” extracted from the South through the integration of low-wage, highly exploited workers into capitalist production. This then becomes a lever for an increase in the reserve army and the rate of exploitation in the North as well.15

Marx and the General Law of Accumulation

In addressing the general law of accumulation, it is important first to take note of a common misconception directed at Marx’s tendential law. It is customary for establishment critics to attribute to Marx—on the basis of one or at most two passages taken out of context—what these critics have dubbed as an “immiseration theory” or a “doctrine of ever-increasing misery.”16 Illustrative of this is John Strachey in his 1956 book Contemporary Capitalism, the larger part of which was devoted to polemicizing against Marx on this point. Strachey repeatedly contended that Marx had “predicted” that real wages would not rise under capitalism, so that workers’ average standard of living must remain constant or decline—presenting this as a profound error on Marx’s part. However, Strachey, together with all subsequent critics who have advanced this view, managed only to provide a single partial sentence in Capital (plus one early on in The Communist Manifesto—not one of Marx’s economic works) as purported evidence for this. Thus in the famous summary paragraph on the “expropriation of the expropriators” at the end of volume one, Marx (as quoted by Strachey) wrote: “While there is thus a progressive diminution in the number of the capitalist magnates (who usurp and monopolise all the advantages of this transformative process) there occurs a corresponding increase in the mass of poverty, oppression, enslavement, degeneration and exploitation….”17

Hardly resounding proof of a crude immiseration thesis! Marx’s point rather was that the system is polarized between the growing monopolization of capital by a relatively smaller number of individual capitals at the top and the relative impoverishment of the great mass of people at the bottom. This passage said nothing about the movement of real wages. Moreover, Strachey deliberately excluded the sentence immediately preceding the one he quoted, in which Marx indicated that he was concerned in this context not simply with the working class of the rich countries but with the entire capitalist world and the global working class—or as he put it, “the entanglement of all peoples in the net of the world market, and, with this, the growth of the international character of the capitalist regime.” Indeed, the “kernel of truth” to the “theory of immiseration,” Roman Rosdolsky wrote in The Making of Marx’s ‘Capital’, lay in the fact that such tendencies towards an absolute increase in human misery can be found “in two spheres: firstly (temporary) in all times of crisis, and secondly (permanent) in the so-called underdeveloped areas of the world.”18

Far from being a crude theory of immiseration, Marx’s general law was an attempt to explain how the accumulation of capital could occur at all: that is, why the growth in demand for labor did not lead to a continual rise in wages, which would squeeze profits and cut off accumulation. Moreover, it served to explain: (1) the functional role that unemployment played in the capitalist system; (2) the reason why crisis was so devastating to the working class as a whole; and (3) the tendency towards the pauperization of a large part of the population. Today it has its greatest significance in accounting for “global labor arbitrage,” i.e., capital’s earning of enormous monopolistic returns or imperial rents by shifting certain sectors of production to underdeveloped regions of the world to take advantage of the global immobility of labor, and the existence of subsistence (or below subsistence) wages in much of the global South.

As Fredric Jameson recently noted in Representing Capital, despite the “mockery” thrown at Marx’s general law of accumulation in the early post-Second World War era, “it is…no longer a joking matter.” Rather, the general law highlights “the actuality today of Capital on a world scale.”19

It is therefore essential to take a close examination of Marx’s argument. In his best-known single statement on the general law of accumulation, Marx wrote:

In proportion as capital accumulates, the situation of the worker, be his payment high or low, must grow worse.… The law which always holds the relative surplus population in equilibrium with the extent and energy of accumulation rivets the worker to capital more firmly than the wedges of Hephaestus held Prometheus to the rock. It makes an accumulation of misery a necessary condition, corresponding to the accumulation of wealth. Accumulation at one pole is, therefore, at the same time accumulation of misery, the torment of labour, slavery, ignorance, brutalization and moral degradation at the opposite pole, i.e. on the side of the class that produces its own product as capital [italics added].20

By pointing to an “equilibrium” between accumulation of capital and the “relative surplus population” or reserve army of labor, Marx was arguing, that under “normal” conditions the growth of accumulation is able to proceed unhindered only if it also results in the displacement of large numbers of workers. The resulting “redundancy” of workers checks any tendency toward a too rapid rise in real wages which would bring accumulation to a halt. Rather than a crude theory of “immiseration,” then, the general law of accumulation highlighted that capitalism, via the constant generation of a reserve army of the unemployed, naturally tended to polarize between relative wealth at the top and relative poverty at the bottom—with the threat of falling into the latter constituting an enormous lever for the increase in the rate of exploitation of employed workers.

Marx commenced his treatment of the general law by straightforwardly observing, as we have noted, that the accumulation of capital, all other things being equal, increased the demand for labor. In order to prevent this growing demand for labor from contracting the available supply of workers, and thereby forcing up wages and squeezing profits, it was necessary that a counterforce come into being that would reduce the amount of labor needed at any given level of output. This was accomplished primarily through increases in labor productivity with the introduction of new capital and technology, resulting in the displacement of labor. (Marx specifically rejected the classical “iron law of wages” that saw the labor force as determined primarily by population growth.) In this way, by “constantly revolutionizing the instruments of production,” the capitalist system is able, no less constantly, to reproduce a relative surplus population or reserve army of labor, which competes for jobs with those in the active labor army.21 “The industrial reserve army,” Marx wrote, “during periods of stagnation and average prosperity, weighs down the active army of workers; during the period of over-production and feverish activity, it puts a curb on their pretensions. The relative surplus population is therefore the background against which the law of the demand and supply of labour does its work. It confines the field of action of this law to the limits absolutely convenient to capital’s drive to exploit and dominate the workers.”22

It followed that if this essential lever of accumulation were to be maintained, the reserve army would need to be continually restocked so as to remain in a constant (if not increasing) ratio to the active labor army. While generals won battles by “recruiting” armies, capitalists won them by “discharging the army of workers.”23

It is important to note that Marx developed his well-known analysis of the concentration and centralization of capital as part the argument on the general law of accumulation. Thus the tendency toward the domination of the economy by bigger and fewer capitals, was as much a part of his overall argument on the general law as was the growth of the reserve army itself. The two processes were inextricably bound together.24

Marx’s breakdown of the reserve army of labor into its various components was complex, and was clearly aimed both at comprehensiveness and at deriving what were for his time statistically relevant categories. It included not only those who were “wholly unemployed” but also those who were only “partially employed.” Thus the relative surplus population, he wrote, “exists in all kinds of forms.” Nevertheless, outside of periods of acute economic crisis, there were three major forms of the relative surplus population: the floating, latent, and stagnant. On top of that there was the whole additional realm of official pauperism, which concealed even more elements of the reserve army.

The floating population consisted of workers who were unemployed due to the normal ups and downs of accumulation or as a result of technological unemployment: people who have recently worked, but who were now out of work and in the process of searching for new jobs. Here Marx discussed the age structure of employment and its effects on unemployment, with capital constantly seeking younger, cheaper workers. So exploitative was the work process that workers were physically used up quickly and discarded at a fairly early age well before their working life was properly over.25

The latent reserve army was to be found in agriculture, where the demand for labor, Marx wrote, “falls absolutely” as soon as capitalist production has taken it over. Hence, there was a “constant flow” of labor from subsistence agriculture to industry in the towns: “The constant movement towards the towns presupposes, in the countryside itself, a constant latent surplus population, the extent of which only becomes evident at those exceptional times when its distribution channels are wide open. The wages of the agricultural labourer are therefore reduced to a minimum, and he always stands with one foot already in the swamp of pauperism.”26

The third major form of the reserve army, the stagnant population, formed, according to Marx, “a part of the active reserve army but with extremely irregular employment.” This included all sorts of part-time, casual (and what would today be called informal) labor. The wages of workers in this category could be said to “sink below the average normal level of the working class” (i.e., below the value of labor power). It was here that the bulk of the masses ended up who had been “made ‘redundant’” by large-scale industry and agriculture. Indeed, these workers represented “a proportionately greater part” of “the general increase in the [working] class than the other elements” of the reserve army.

The largest part of this stagnant reserve army was to be found in “modern domestic industry,” which consisted of “outwork” carried out through the agency of subcontractors on behalf of manufacture, and dominated by so-called “cheap labor,” primarily women and children. Often such “outworkers” outweighed factory labor in an industry. For example, a shirt factory in Londonderry employed 1,000 workers but also had another 9,000 outworkers attached to it stretched out over the countryside. Here the most “murderous side of the economy” was revealed.27

For Marx, pauperism constituted “the lowest sediment of the relative surplus population” and it was here that the “precarious…condition of existence” of the entire working population was most evident. “Pauperism,” he wrote, “is the hospital of the active labor-army and the dead weight of the industrial reserve army.” Beyond the actual “lumpenproletariat” or “vagabonds, criminals, prostitutes,” etc., there were three categories of paupers. First, those who were able to work, and who reflected the drop in the numbers of the poor in every period of industrial prosperity, when the demand for labor was greatest. These destitute elements employed only in times of prosperity were an extension of the active labor army. Second, it included orphans and pauper children, who in the capitalist system were drawn into industry in great numbers during periods of expansion. Third, it encompassed “the demoralized, the ragged, and those unable to work, chiefly people who succumb to their incapacity for adaptation, an incapacity that arises from the division of labour; people who have lived beyond the worker’s average life-span; and the victims of industry whose number increases with the growth of dangerous machinery, of mines, chemical workers, etc., the mutilated, the sickly, the widows, etc.” Such pauperism was a creation of capitalism itself, “but capital usually knows how to transfer these [social costs] from its own shoulders to those of the working class and the petty bourgeoisie.”28

The full extent of the global reserve army was evident in periods of economic prosperity, when much larger numbers of workers were temporarily drawn into employment. This included foreign workers. In addition to the sections of the reserve armies mentioned above, Marx noted that Irish workers were drawn into employment in English industry in periods of peak production—such that they constituted part of the relative surplus population for English production.29 The temporary reduction in the size of the reserve army in comparison to the active labor army at the peak of the business cycle had the effect of pulling up wages above their average value and squeezing profits—though Marx repeatedly indicated that such increases in real wages were not the principal cause of crises in profitability, and never threatened the system itself.30

During an economic crisis, many of the workers in the active labor army would themselves be made “redundant,” thereby increasing the numbers of unemployed on top of the normal reserve army. In such periods, the enormous weight of the relative surplus population would tend to pull wages down below their average value (i.e., the historically determined value of labor power). As Marx himself put it: “Stagnation in production makes part of the working class idle and hence places the employed workers in conditions where they have to accept a fall in wages, even below the average.”31 Hence, in times of economic crisis, the working class as an organic whole, encompassing the active labor army and the reserve army, was placed in dire conditions, with a multitude of people succumbing to hunger and disease.

Marx was unable to complete his critique of political economy, and consequently never wrote his projected volume on world trade. Nevertheless, it is clear that he saw the general law of accumulation as extending eventually to the world level. Capital located in the rich countries, he believed, would take advantage of cheaper labor abroad—and of the higher levels of exploitation in the underdeveloped parts of the world made possible by the existence of vast surplus labor pools (and non-capitalist modes of production). In his speech to the Lausanne Congress of the First International in 1867 (the year of the publication of the first volume of Capital) he declared: “A study of the struggle waged by the English working class reveals that, in order to oppose their workers, the employers either bring in workers from abroad or else transfer manufacture to countries where there is a cheap labor force. Given this state of affairs, if the working class wishes to continue its struggle with some chance of success, the national organisations must become international.”32

The reality of unequal exchange, whereby, in Marx’s words, “the richer country exploits the poorer, even where the latter gains by the exchange,” was a basic, scientific postulate of classical economy, to be found in both Ricardo and J.S. Mill. These higher profits were tied to the cheapness of labor in poor countries—attributable in turn to underdevelopment, and a seemingly unlimited labor supply (albeit much of it forced labor). “The profit rate,” Marx observed, “is generally higher there [in the colonies] on account of the lower degree of development, and so too is the exploitation of labour, through the use of slaves, coolies, etc.” In all trade relations, the richer country was in a position to extract what were in effect “monopoly profits” (or imperial rents) since “the privileged country receives more labour in exchange for less,” while inversely, “the poorer country gives more objectified labour in kind than it receives.” Hence, as opposed to a single country where gains and losses evened out, it was quite possible and indeed common, Marx argued, for one nation to “cheat” another. The growth of the relative surplus population, particularly at the global level, represented such a powerful influence in raising the rate of exploitation, in Marx’s conception, that it could be seen as a major “counterweight” to the tendency of the rate of profit to fall, “and in part even paralyse[s] it.”33

The one classical Marxist theorist who made useful additions to Marx’s reserve army analysis with respect to imperialism was Rosa Luxemburg. In The Accumulation of Capital she argued that in order for accumulation to proceed “capital must be able to mobilise world labour power without restriction.” According to Luxemburg, Marx had been too “influenced by English conditions involving a high level of capitalist development.” Although he had addressed the latent reserve in agriculture, he had not dealt with the drawing of surplus labor from non-capitalist modes of production (e.g., the peasantry) in his description of the reserve army. However, it was mainly here that the surplus labor for global accumulation was to be found. It was true, Luxemburg acknowledged, that Marx discussed the expropriation of the peasantry in his treatment of “so-called primitive accumulation,” in the chapter of Capital immediately following his discussion of the general law. But that argument was concerned primarily with the “genesis of capital” and not with its contemporary forms. Hence, the reserve army analysis had to be extended in a global context to take into account the enormous “social reservoir” of non-capitalist labor.34

Global Labor Arbitrage

The pursuit of “an ever extended market” Marx contended, is an “inner necessity” of the capitalist mode of production.35 This inner necessity took on a new significance, however, with the rise of monopoly capitalism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The emergence of multinational corporations, first in the giant oil companies and a handful of other firms in the early twentieth century, and then becoming a much more general phenomenon in the post-Second World War years, was a product of the concentration and centralization of capital on a world scale; but equally involved the transformation of world labor and production.

It was the increasing multinational corporate dominance over the world economy, in fact, that led to the modern concept of “globalization,” which arose in the early 1970s as economists, particularly those on the left, tried to understand the way in which the giant firms were reorganizing world production and labor conditions.36 This was clearly evident by the early 1970s—not only in Hymer’s work, but also in Richard Barnet and Ronald Müller’s influential 1974 work, Global Reach, in which they argued: “The rise of the global corporation represents the globalization of oligopoly capitalism.” This was “the culmination of a process of concentration and internationalization that has put the world economy under the substantial control of a few hundred business enterprises which do not compete with one another according to the traditional rules of the market.” Moreover, the implications for labor were enormous. Explaining how oligopolistic rivalry now meant searching for the lowest unit labor costs worldwide, Barnet and Müller argued that this had generated “the ‘runaway shop’ which becomes the ‘export platform’ in an underdeveloped country,” and which had become a necessity of business for U.S. companies, just like their European and Japanese competitors.37

Over the past half century, these global oligopolies have been offshoring whole sectors of production from the rich/high-wage to the poor/low-wage countries, transforming global labor conditions in their search for global low-cost position, and in a divide and rule approach to world labor. Leading U.S. multinationals, such as General Electric, Exxon, Chevron, Ford, General Motors, Proctor and Gamble, IBM, Hewlett Packard, United Technologies, Johnson and Johnson, Alcoa, Kraft, and Coca Cola now employ more workers abroad than they do in the United States—even without considering the vast number of workers they employ through subcontractors. Some major corporations, such as Nike and Reebok, rely on third world subcontractors for 100 percent of their production workforce—with domestic employees confined simply to managerial, product development, marketing, and distribution activities.38 The result has been the proletarianization, often under precarious conditions, of much of the population of the underdeveloped countries, working in massive export zones under conditions dictated by foreign multinationals.

Two realities dominate labor at the world level today. One is global labor arbitrage or the system of imperial rent. The other is the existence of a massive global reserve army, which makes this world system of extreme exploitation possible. “Labour arbitrage” is defined quite simply by The Economist as “taking advantage of lower wages abroad, especially in poor countries.” It is thus an unequal exchange process in which one country, as Marx said, is able to “cheat” another due to the much higher exploitation of labor in the poorer country.39 A study of production in China’s industrialized Pearl River Delta region (encompassing Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong) found in 2005 that some workers were compelled to work up to sixteen hours continuously, and that corporal punishment was routinely employed as a means of worker discipline. Some 200 million Chinese are said to work in hazardous conditions, claiming over a 100,000 lives a year.40

It is such superexploitation that lies behind much of the expansion of production in the global South.41 The fact that this has been the basis of rapid economic growth for some emerging economies does not alter the reality that it has generated enormous imperial rents for multinational corporations and capital at the center of the system. As labor economist Charles Whalen has written, “The prime motivation behind offshoring is the desire to reduce labor costs…a U.S.-based factory worker hired for $21 an hour can be replaced by a Chinese factory worker who is paid 64 cents an hour…. The main reason offshoring is happening now is because it can.”42

How this system of global labor arbitrage occurs by way of global supply chains, however, is enormously complex. Dell, the PC assembler, purchases some 4,500 parts from 300 different suppliers in multiple countries around the world.43 As the Asian Development Bank Institute indicated in a 2010 study of iPhone production: “It is almost impossible [today] to define clearly where a manufactured product is made in the global market. This is why on the back of iPhones one can read ‘Designed by Apple in California, Assembled in China.’” Although both statements on the back of the iPhones are literally correct, neither answers the question of where the real production takes place. Apple does not itself manufacture the iPhone. Rather the actual manufacture (that is, everything but its software and design) takes place primarily outside the United States. The production of iPhone parts and components is carried out principally by eight corporations (Toshiba, Samsung, Infineon, Broadcom, Numonyx, Murata, Dialog Semiconductor, and Cirrus Logic), which are located in Japan, South Korea, Germany, and the United States. All of the major parts and components of the iPhone are then shipped to the Shenzhen, China plants of Foxconn (a company headquartered in Taipei) for assembly and export to the United States.

Apple’s enormous, complex global supply chain for iPod production is aimed at obtaining the lowest unit labor costs (taking into consideration labor costs, technology, etc.), appropriate for each component, with the final assembly taking place in China, where production occurs on a massive scale, under enormous intensity, and with ultra-low wages. In Foxconn’s Longhu, Shenzhen factory 300,000 to 400,000 workers eat, work, and sleep under horrendous conditions, with workers, who are compelled to do rapid hand movements for long hours for months on end, finding themselves twitching constantly at night. Foxconn workers in 2009 were paid the minimum monthly wage in Shenzhen, or about 83 cents an hour. (Overall in China in 2008 manufacturing workers were paid $1.36 an hour, according to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data.)

Despite the massive labor input of Chinese workers in assembling the final product, their low pay means that their work only amounts to 3.6 percent of the total manufacturing cost (shipping price) of the iPhone. The overall profit margin on iPhones in 2009 was 64 percent. If iPhones were assembled in the United States—assuming labor costs ten times that in China, equal productivity, and constant component costs—Apple would still have an ample profit margin, but it would drop from 64 percent to 50 percent. In effect, Apple makes 22 percent of its profit margin on iPhone production from the much higher rate of exploitation of Chinese labor.44

Of course in stipulating a mere tenfold difference in wages between the United States and China, in its calculation of the lower profit margins to be gained with United States as opposed to Chinese assembly, the Asian Development Bank Institute was adopting a very conservative assumption. Overall Chinese manufacturing workers in 2008, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, received only 4 percent of the compensation for comparable work in the United States, and 3 percent of that in the European Union.45 In comparison, hourly manufacturing wages in Mexico in 2008 were about 16 percent of the U.S. level.46

In spite of the low-wage “advantage” of China, some areas of Asia, such as Cambodia, Vietnam, and Bangladesh, have hourly compensation levels still lower, leading to a divide and rule tendency for multinational corporations—commonly acting through subcontractors—to locate some sectors of production, such as light industrial textile production, primarily in these still lower wage countries. Thus the New York Times indicated in July 2010, that Li & Fung, a Hong Kong-based company “that handles sourcing and apparel manufacturing for companies like Wal-Mart and Liz Claiborne” increased its production in Bangladesh by 20 percent in 2010, while China, its biggest supplier, slid 5 percent. Garment workers in Bangladesh earned around $64 a month, compared “to minimum wages in China’s coastal industrial provinces ranging from $117 to $147 a month.”47

For multinational corporations there is a clear logic to all of this. As General Electric CEO Jeffrey Immelt stated, the “most successful China strategy”—with China here clearly standing for global labor arbitrage in general—“is to capitalize on its market growth while exporting its deflationary power.” This “deflationary power” has to do of course with lower labor costs (and lower costs of reproduction of labor in the North through the lowering of the costs of wage-consumption goods). It thus represents a global strategy for raising the rate of surplus value (widening profit margins).48

Today Marx’s reserve army analysis is the basis, directly and indirectly (even in corporate circles) for ascertaining how long the extreme exploitation of low-wage workers in the underdeveloped world will persist. In 1997 Jannik Lindbaek, executive vice president of the International Finance Corporation, presented an influential paper entitled “Emerging Economies: How Long Will the Low-Wage Advantage Last?” He pointed out that international wage differentials were enormous, with labor costs for spinning and weaving in rich countries exceeding that of the lowest wage countries (Pakistan, Madagascar, Kenya, Indonesia, and China) by a factor of seventy-to-one in straight dollar terms, and ten-to-one in terms of purchasing power parity (taking into account the local cost of living).

The central issue from the standpoint of global capital, Lindbaek indicated, was China, which had emerged as an enormous platform for production, due to its ultra-low wages and seemingly unlimited supply of labor. The key strategic question then was, “How long will China’s low wage advantage last?” His answer was that China’s “enormous ‘reserve army of labor’…will be released gradually as agricultural productivity improves and jobs are created in the cities.” Looking at various demographic factors, including the expected downward shift in the number of working-age individuals beginning in the second decade of the twenty-first century, Lindbaek indicated that real wages in China would eventually rise above subsistence. But when?49

In mainstream economics, the analysis of the role of surplus labor in holding down wages in the global South draws primarily on W. Arthur Lewis’s famous article “Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour,” published in 1954. Basing his argument on the classical economics of Adam Smith and Marx (relying in fact primarily on the latter), Lewis argued that in third world countries with vast, seemingly “unlimited” supplies of labor, capital accumulation could occur at a high rate while wages remained constant and at subsistence level. This was due to the very high reserve army of labor, including “the farmers, the casuals, the petty traders, the retainers (domestic and commercial), women in the household, and population growth.” Although Lewis (in his original article on the subject) erroneously confined Marx’s own reserve army concept to the narrow question of technological unemployment—claiming on this basis that Marx was wrong on empirical grounds—he in fact adopted the broader framework of Marx’s reserve army analysis as his own. Thus he pointed to the enormous latent surplus population in agriculture. He also turned to Marx’s notion of primitive accumulation, to indicate how the depeasantization of the non-capitalist sector might take place.

Lewis, however, is best known within mainstream economics for having argued that eventually a turning point would occur. At some point capital accumulation would exceed the supply of surplus labor (primarily from a slowdown in internal migration from the countryside) resulting in a rise in the real wages of workers in industry. As he put it, “the process” of accumulation with “unlimited labor” and hence constant real wages must eventually stop “when capital accumulation has caught up with the labour supply.”50

Today the Lewisian framework, overlapping with Marx’s reserve army theory and in fact derived from it—but propounding the view (which Marx did not) that the reserve army of labor will ultimately be transcended in poor countries as part of a smooth path of capitalist development—is the primary basis on which establishment economics raises the issue of how long global labor arbitrage can last, particularly in relation to China. The concern is whether the huge imperial rents now being received from the superexploitation of labor in the poor countries will rapidly shrink or even disappear. The Economist magazine, for example, worries that a Lewisian turning point, combined with growing labor revolts in China, will soon bring to an end the huge surplus profits from the China trade. Chinese workers “in the cities at least,” it complains, “are now as expensive as their Thai or Filipino peers.” “The end of surplus labor,” The Economist declares, “is not an event, but a process. And that process may already be under way.” A whole host of factors, such as demography, the stability of Chinese rural labor with its family plots, and the growing organization of workers, may cause labor constraints to come into play earlier than had been expected. At the very least, The Economist suggests, the enormous gains of capital in the North that occurred “between 1997 and 2005 [when] the price of Chinese exports to America fell by more than 12%” are unlikely to be repeated. And if wages in China rise, cutting into imperial rents, where will multinational corporations turn? “Vietnam is cheap: its income per person is less than a third of China’s. But its pool of workers is not that deep.”51

Writing in Monthly Review, economist Minqi Li notes that since the early 1980s 150 million workers in China have migrated from rural to urban areas. China thus experienced a 13 percentage-point drop (from 50 percent to 37 percent) in the share of wages in GDP between 1990 and 2005. Now “after many years of rapid accumulation, the massive reserve army of cheap labor in China’s rural areas is starting to become depleted.” Li focuses mainly on demographic analysis, indicating that China’s total workforce is expected to peak at 970 million by 2012, and then decline by 30 million by 2020, with the decline occurring more rapidly among the prime age working population. This he believes will improve the bargaining power of workers and strengthen industrial strife in China, raising issues of radical transformation. Such industrial strife will inevitably mount if China’s non-agricultural population passes “the critical threshold of 70 percent by around 2020.”52

Others think that global labor arbitrage with respect to China is far from over. Yang Yao, an economist at Peking University, argues that “the countryside still has 45% of China’s labour force,” a huge reserve army of hundreds of millions, much of which will become available to industry as mechanization proceeds. Stephen Roach has observed that with Chinese wages at 4 percent of U.S. wages, there is “barely…a dent in narrowing the arbitrage with major industrial economies”—while China’s “hourly compensation in manufacturing” is “less than 15% of that elsewhere in East Asia” (excluding Japan), and well below that of Mexico.53

The Global Reserve Army

In order to develop a firmer grasp of this issue it is crucial to look both empirically and theoretically at the global reserve army as it appears in the current historical context—and then bring to bear the entire Marxian critique of imperialism. Without such a comprehensive critique, analyses of such problems as the global shift in production, the global labor arbitrage, deindustrialization, etc., are mere partial observations suspended in mid-air.

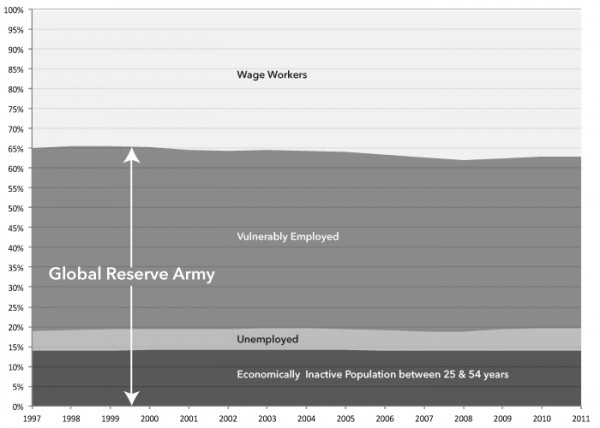

The data on the global workforce compiled by the ILO conforms closely to Marx’s main distinctions with regard to the active labor army and the reserve army of labor. In the ILO picture of the world workforce in 2011, 1.4 billion workers are wage workers—many of whom are precariously employed, and only part-time workers. In contrast, the number of those counted as unemployed worldwide in 2009 consisted of only 218 million workers. (In order to be classified as unemployed, workers need to have actively pursued job searches in the previous few weeks). The unemployed, in this sense, can be seen as conforming roughly to Marx’s “floating” portion of the reserve army.

A further 1.7 billion workers are classified today as “vulnerably employed.” This is a residual category of the “economically active population,” consisting of all those who work but are not wage workers—or part of the active labor army in Marx’s terminology. It includes two categories of workers: “own–account workers” and “contributing family workers.”

“Own-account workers,” according to the ILO, encompasses workers engaged in a combination of “subsistence and entrepreneurial activities.” The urban component of the “own-account workers” in third-world countries is primarily made up of workers in the informal sector, i.e. street workers of various kinds, while the agricultural component consists largely of subsistence agriculture. “The global informal working class,” Mike Davis observed in Planet of the Slums, “is about one billion strong, making it the fastest-growing, and most unprecedented, social class on earth.”54

The second category of the vulnerably employed, “contributing family workers,” consists of unpaid family workers. For example, in Pakistan “more than two-thirds of the female workers that entered employment during 1999/00 to 2005/06 consisted of contributing family workers.”55

The “vulnerably employed” thus includes the greater part of the vast pools of underemployed outside official unemployment rolls, in poor countries in particular. It reflects the fact that, as Michael Yates writes, “In most of the world, open unemployment is not an option; there is no safety net of unemployment compensation and other social welfare programs. Unemployment means death, so people must find work, no matter how onerous the conditions.”56 The various components of vulnerably employed workers correspond to what Marx described as the “stagnant” and “latent” portions of the reserve army.

Additionally, many individuals of working age are classified as not belonging to the economically active population, and thus as economically inactive. For the prime working ages of 25–54 years this adds up, globally, to 538 million people in 2011. This is a very heterogeneous grouping including university students, primarily in wealthier countries; the criminal element engendered at the bottom of the capitalist economy (what Marx called the lumpenproletariat); discouraged and disabled workers, who have been marginalized by the system; and in general what Marx called the pauperized portion of the working class—that portion of working age individuals, “the demoralized, the ragged,” and the disabled, who have been almost completely shut out of the labor force. It is here, he argued, that one finds the most “precarious…condition of existence.” Officially designated “discouraged workers” are a significant number of would-be workers. According to the ILO, if discouraged workers are included in Botswana’s unemployment rate in 2006 it nearly doubles from 17.5 percent to 31.6 percent.57

If we take the categories of the unemployed, the vulnerably employed, and the economically inactive population in prime working ages (25–54) and add them together, we come up with what might be called the maximum size of the global reserve army in 2011: some 2.4 billion people, compared to 1.4 billion in the active labor army. It is the existence of a reserve army that in its maximum extent is more than 70 percent larger than the active labor army that serves to restrain wages globally, and particularly in the poorer countries. Indeed, most of this reserve army is located in the underdeveloped countries of the world, though its growth can be seen today in the rich countries as well. The breakdown in percentages of its various components can be seen in Chart 2.

Chart 2. The Global Workforce and the Global Reserve Army

Notes: The Proportion of “vulnerably employed” and “unemployed” were estimated based on percentages from the “Global Employment Trends” reports cited below. The chart includes total world population (15 years and over) excluding the economically inactive population less than 25- and greater than 54-years of age.

Sources: International Labour Office (ILO), “Economically Active Population Estimates and Projections (5th edition, revision 2009),” LABORSTA Internet (Geneva: International Labour Organisation, 2009); ILO “Global Employment Trends,” 2009, 2010 and 2011 (Geneva: International Labour Office).

The enormous reserve army of labor depicted in Chart 2 is meant to capture its maximum extent. Some will no doubt be inclined to argue that many of the workers in the vulnerably employed do not belong to the reserve army, since they are peasant producers, traditionally thought of as belonging to non-capitalist production—including subsistence workers who have no relation to the market. It might be contended that these populations are altogether outside the capitalist market. Yet, this is hardly the viewpoint of the system itself. The ILO classifies them generally, along with informal workers, as “vulnerably employed,” recognizing they are economically active and employed, but not wage workers. From capital’s developmental standpoint, the vulnerably employed are all potential wage workers—grist for the mill of capitalist development. Workers engaged in peasant production are viewed as future proletarians, to be drawn more deeply into the capitalist mode.

In fact, the figures we provide for the maximum extent of global reserve army, in an attempt to understand the really-existing relative surplus population, might be seen in some ways as underestimates. In Marx’s conception, the reserve army also included part-time workers. Yet, due to lack of data, it is impossible to include this element in our global reserve army estimates. Further, figures on the economically inactive population’s share of the reserve army include only prime age workers between 24 and 54 years of age without work, and exclude all of those ages 16–23 and 55–65. Yet, from a practical standpoint, in most countries, those in these ages too need and have a right to employment.

Despite uncertainties related to the ILO data, there can be no doubt about the enormous size of the global reserve army. We can understand the implications of this more fully by looking at Samir Amin’s analysis of “World Poverty, Pauperization, and Capital Accumulation” in Monthly Review in 2003. Amin argued that “Modern capitalist agriculture—encompassing both rich, large-scale family farming and agribusiness corporations—is now engaged in a massive attack on third world peasant production.” According to the core capitalist view propounded by the WTO, the World Bank, and the IMF, rural (mostly peasant) production is destined to be transformed into advanced capitalist agriculture on the model of the rich countries. The 3 billion plus rural workers would be replaced in the ideal capitalist scenario, as Amin puts it, by some “twenty million new modern farmers.”

In the dominant view, these workers would then be absorbed by industry, primarily in urban centers, on the model of the developed capitalist countries. But Britain and the other European economies, as Amin and Indian economist Prabhat Patnaik point out, were not themselves able to absorb their entire peasant population within industry. Rather, their surplus population emigrated in great numbers to the Americas and to various colonies. In 1820 Britain had a population of 12 million, while between 1820 and 1915 emigration was 16 million. Put differently, more than half the increase in British population emigrated each year during this period. The total emigration from Europe as a whole to the “new world” (of “temperate regions of white settlement”) over this period was 50 million.

While such mass emigration was a possibility for the early capitalist powers, which moved out to seize large parts of the planet, it is not possible for countries of the global South today. Consequently, the kind of reduction in peasant population currently pushed by the system points, if it were effected fully, to mass genocide. An unimaginable 7 percent annual rate of growth for fifty years across the entire global South, Amin points out, could not absorb even a third of this vast surplus agricultural population. “No amount of economic growth,” Yates adds, will “absorb” the billions of peasants in the world today “into the traditional proletariat, much less better classes of work.”

The problem of the absorption of the massive relative surplus population in these countries becomes even more apparent if one looks at the urban population. There are 3 billion plus people who live in urban areas globally, concentrated in the massive cities of the global South, in which people are crowded together under increasingly horrendous, slum conditions. As the UN Human Settlements Programme declared in The Challenge of the Slums: “Instead of being a focus of growth and prosperity, the cities have become a dumping ground for a surplus population working in unskilled, unprotected and low-wage informal service industries and trade.”

For Amin, all of this is tied to an overall theory of unequal exchange/imperialist rent. The “conditions governing accumulation on a world scale…reproduce unequal development. They make clear that underdeveloped countries are so because they are superexploited and not because they are backward.” The system of imperialist rent associated with such superexploitation, reaches its mature form and is universalized with the development of “the later capitalism of the generalized, financialized, and globalized oligopolies.”58

Prabhat Patnaik has developed a closely related perspective, focusing on the reserve army of labor in The Value of Money and other recent works. He begins by questioning the standard economic view that it is low labor productivity rather than the existence of enormous labor reserves that best explains the impoverishment of countries in the global South. Even in economies that have experienced accelerated growth and rising productivity, such as India and China, he argues, “labour reserves continue to remain non-exhausted.” This is because with the high rate of productivity growth (and labor displacement) associated with the shift toward production of high-technology goods, “the rate of growth of labour demand…does not adequately exceed the rate of growth of labor supply”—adequately enough, that is, to draw down the labor reserves sufficiently, and thus to pull wages up above the subsistence level. An illustration of the productivity dynamic and how it affects labor absorption can be seen in the fact that, despite rock-bottom wages in China, Foxconn is planning to introduce a million robots in its plants within three years as part of its strategy of displacing workers in simple assembly operations. Foxconn currently employs a million workers in mainland China, many of whom assemble iPhones and iPads.

Patnaik’s argument is clarified by his use of a dual reserve army model: the “precapitalist-sector reserve army” (inspired by Luxemburg’s analysis) and the “internal reserve army.” In essence, capitalism in China and India is basing its exports more and more on high-productivity, high-technology production, which means the displacement of labor, and the creation of an expanding internal reserve army. Even at rapid rates of growth therefore it is impossible to absorb the precapitalist-sector reserve army, the outward flow of which is itself accelerated by mechanization.59

Aside from the direct benefits of enormously high rates of exploitation, which feed the economic surplus flowing into the advanced capitalist countries, the introduction of low-cost imports from “feeder economies” in Asia and other parts of the global South by multinational corporations has a deflationary effect. This protects the value of money, particularly the dollar as the hegemonic currency, and thus the financial assets of the capitalist class. The existence of an enormous global reserve army of labor thus forces income deflation on the world’s workers, beginning in the global South, but also affecting the workers of the global North, who are increasingly subjected to neoliberal “labour market flexibility.”

In today’s phase of imperialism—which Patnaik identifies with the development of international finance capital—“wages in the advanced countries cannot rise, and if anything tend to fall in order to make their products more competitive” in relation to the wage “levels that prevail in the third world.” In the latter, wage levels are no higher, “than those needed to satisfy some historically-determined subsistence requirements,” due to the existence of large labor reserves. This logic of world exploitation is made more vicious by the fact that “even as wages in the advanced countries fall, at the prevailing levels of labor productivity, labor productivity in third world countries moves up, at the prevailing level of wages, towards the level reached in the advanced countries. This is because the wage differences that still continue to exist induce a diffusion of activities from the former to the latter. This double movement means that the share of wages in total world output decreases,” while the rate of exploitation worldwide rises.60

What Patnaik has called “the paradox of capitalism” is traceable to Marx’s general law of accumulation: the tendency of the system to concentrate wealth while expanding relative (and even absolute) poverty. “In India, precisely during the period of neoliberal reforms when output growth rates have been high,” Patnaik notes,

there has been an increase in the proportion of the rural population accessing less than 2400 calories per person per day (the figure for 2004 is 87 percent). This is also the period when hundreds of thousands of peasants, unable to carry on even simple reproduction, have committed suicide. The unemployment rate has increased, notwithstanding a massive jump in the rate of capital accumulation; and the real wage rate, even of the workers in the organized sector, has at best stagnated, notwithstanding massive increases in labor productivity. In short our own experience belies Keynesian optimism about the future of mankind under capitalism.61

In the advanced capitalist countries, the notion of “precariousness,” which Marx in his reserve army discussion employed to describe the most pauperized sector of the working class, has been rediscovered, as conditions once thought to be confined to the third world, are reappearing in the rich countries. This has led to references to the emergence of a “new class”—though in reality it is the growing pauperized sector of the working class—termed the “precariat.”62

At the bottom of this precariat developing in the rich countries are so-called “guest workers.” As Marx noted, in the nineteenth century, capital in the wealthy centers is able to take advantage of lower-wage labor abroad either through capital migration to low-wage countries, or through the migration of low-wage labor into rich countries. Although migrant labor populations from poor countries have served to restrain wages in rich countries, particularly the United States, from a global perspective the most significant fact with respect to workers migrating from South to North is their low numbers in relation to the population of the global South.

Overall the share of migrants in total world population has shown no appreciable change since the 1960s. According to the ILO, there was only “a very small rise” in the migration from developing to developed countries “in the 1990s, and…this is accounted for basically by increased migration from Central American and Caribbean countries to the United States.” The percentage of adult migrants from developing to developed countries in 2000 was a mere 1 percent of the adult population of developing countries. Moreover, those migrants were concentrated among the more highly skilled so that “the effect of international migration on the low-skilled labour force” in developing countries themselves “has been negligible for the most part…. Migration from developing to developed countries has largely meant brain drain…. In short,” the ILO concludes, “limited as it was, international migration” in the decade of the 1990s “served to restrain the growth of skill intensity of the labour force in quite a large number of developing countries, and particularly in the least developed countries.” All of this drives home the key point that capital is internationally mobile, while labor is not.63

If the new imperialism has its basis in the superexploitation of workers in the global South, it is a phase of imperialism that in no way can be said to benefit the workers of the global North, whose conditions are also being dragged down—both by the disastrous global wage competition introduced by multinationals, and, more fundamentally, by the overaccumulation tendencies in the capitalist core, enhancing stagnation, and unemployment.64

Indeed, the wealthy countries of the triad (the United States, Europe, and Japan) are all bogged down in conditions of deepening stagnation, resulting from their incapacity to absorb all of the surplus capital that they are generating internally and pulling in from abroad—a contradiction which is manifested in weakening investment and employment. Financialization, which helped to boost these economies for decades, is now arrested by its own contradictions, with the result that the root problems of production, which financial bubbles served to cover up for a time, are now surfacing. This is manifesting itself not only in diminishing growth rates, but also rising levels of excess capacity and unemployment. In an era of globalization, financialization, and neoliberal economic policy, the state is unable effectively to move in to correct the problem, and is increasingly geared simply to bailing out capital, at the expense of the rest of society

The imperial rent that these countries appropriate from the rest of the world only makes the problems of surplus absorption or overaccumulation at the center of the world system worse. “Foreign investment, far from being an outlet for domestically generated surplus,” Baran and Sweezy famously wrote in Monopoly Capital, “is a most efficient process for transferring surplus generated from abroad to the investing country. Under these circumstances, it is of course obvious that foreign investment aggravates rather than helps to solve the surplus absorption problem.”65

The New Imperialism

As we have seen, there can be no doubt about the sheer scale of the relative shift of world manufacturing to the global South in the period of the internationalization of monopoly capital since the Second World War—and accelerating in recent decades. Although this is often seen as a post-1974 or a post-1989 phenomenon, Hymer, Magdoff, Sweezy, and Amin captured the general parameters of this broad movement in accumulation and imperialism, associated with the development of multinational corporations (the internationalization of monopoly capital) as early as the 1970s. Largely as a result of this epochal shift in the center of gravity of world manufacturing production toward the South, about a dozen emerging economies have experienced phenomenal growth rates of 7 percent or more for a quarter century.

Most important among these of course is China, which is not only the most populous country but has experienced the fastest growth rates, reputedly 9 percent or above. At a 7 percent rate of growth an economy doubles in size every ten years; at 9 percent every eight years. Yet, the process is not, as mainstream economics often suggests, a smooth one. The Chinese economy has doubled in size three times since 1978, but wages remain at or near subsistence levels, due to an internal reserve army in the hundreds of millions. China may be emerging as a world economic power, due to its sheer size and rate of growth, but wages remain among the lowest in the world. India’s per capita income, meanwhile, is one-third of China’s. China’s rural population is estimated at 45–50 percent, while India’s is around 70 percent.66

Orthodox economic theorists rely on an abstract model of development that assumes all countries pass through the same phases, and eventually move up from labor-intensive manufacturing to capital-intensive, knowledge-intensive production. This raises the issue of the so-called “middle-income transition” that is supposed to occur at a per capita income of somewhere between $5,000 and $10,000 (China’s per capita income at current exchange rates is about $3,500). Countries in the middle-income transition have higher wage rates and are faced with uncompetitiveness unless they can move to products that capture more value and are less labor-intensive. Most countries fail to make the transition and the middle-income level ends up being a developmental trap. Based on this framework, New York University economist Michael Spence argues in The Next Convergence that China’s “labor-intensive export sectors that have been a major contributor to growth are losing competiveness and have to be allowed to decline or move inland and then eventually decline. They will be replaced by sectors that are more capital, human-capital, and knowledge intensive.”67

Spence’s orthodox argument, however, denies the reality of contemporary China, where the latent reserve army in agriculture alone amounts to hundreds of millions of people. Moving toward a less labor-intensive system under capitalism means higher rates of productivity and technological displacement of labor, requiring that the economy absorb a mounting reserve army by conquering ever-larger, high-value-capture markets. The only cases where anything resembling this has taken place—aside from Japan, which first emerged as a rapidly expanding, militarized-imperialist economy in the early twentieth century—were the Asian tigers (South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong), which were able to expand their external export markets for high value-capture production in the global North during a period of world economic expansion (not the deepening stagnation of today). This is unlikely to prove possible for China and India, which must find employment between them for some 40 percent of the world’s labor force—and to a mounting degree in the urban industrial sector. Unlike Europe during its colonial period the emigration of large pools of surplus labor as an escape valve is not possible: they have nowhere to go. China’s capacity to promote internal-based accumulation (not relying primarily on export markets), meanwhile, is hindered under today’s capitalist conditions by this same reserve army of low-paid labor, and by rapidly rising inequality.

All of this suggests that at some point the contradictions of China’s unprecedented accumulation rates combined with massive labor reserves that cannot readily be absorbed by the accumulation process—particularly with the growing shift to high-technology, high-productivity production—are bound to come to a head.

Meanwhile, international monopoly capital uses its combined monopolies over technology, communications, finance, military, and the planet’s natural resources to control (or at least constrain) the direction of development in the South.68

As the contradictions between North and South of the world system intensify, so do the internal contradictions within them—with class differences widening everywhere. The relative “deindustrialization” in the global North is now too clear a tendency to be altogether denied. Thus the share of manufacturing in U.S. GDP has dropped from around 28 percent in the 1950s to 12 percent in 2010, accompanied by a dramatic decrease in its share (along with that of the OECD as a whole) in world manufacturing.69 Yet, it is important to understand that this is only the tip of the iceberg where the growing worldwide destabilization and overexploitation of labor is concerned.

Indeed, one should never forget the moral barbarism of a system that in 1992 paid Michael Jordan $20 million to market Nikes—an amount equal to the total payroll of the four Indonesian factories involved in the production of the shoes, with women in these factories earning only 15 cents an hour and working eleven-hour days.70 Behind this lies the international “sourcing” strategies of increasingly monopolistic multinational corporations. The field of operation of Marx’s general law of accumulation is now truly global, and labor everywhere is on the defensive.

The answer to the challenges facing world labor that Marx gave at the Lausanne Congress in 1867 remains the only possible one: “If the working class wishes to continue its struggle with some chance of success the national organisations must become international.” It is time for a new International.71

Notes

- ↩ Stephen Herbert Hymer, The Multinational Corporation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), 41, 75, 183.

- ↩ Hymer, The Multinational Corporation, 81, 86, 161, 262–69.

- ↩ Gary Gereffi, The New Offshoring of Jobs and Global Development, ILO Social Policy Lectures, Jamaica, December 2005 (Geneva: International Institute for Labour Studies, 2006), http://ilo.org, 1; Peter Dicken, Global Shift (New York: Guilford Press, 1998), 26–28.

- ↩ Thorstein Veblen already understood this in the 1920s. See his Absentee Ownership and Business Enterprise in Recent Times (New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1964), 287.

- ↩ See Paul M. Sweezy, Four Lectures on Marxism (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1981), 64–65; Michael E. Porter, Competitive Strategy (New York: The Free Press, 1980), 35–36.

- ↩ Ajit K. Ghose, Nomaan Maji, and Christoph Ernst, The Global Employment Challenge (Geneva: International Labour Organisation, 2008), 9–10. On depeasantization see Farshad Araghi, “The Great Global Enclosure of Our Times,” in Fred Magdoff, John Bellamy Foster, and Frederick H. Buttel, eds., Hungry for Profit (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000), 145–60.

- ↩ John Smith, Imperialism and the Globalisation of Production (Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sheffield, July 2010), 224.

- ↩ Stephen Roach, “How Global Labor Arbitrage Will Shape the World Economy,” Global Agenda Magazine, 2004,http://ecocritique.free.fr; John Bellamy Foster, Harry Magdoff, and Robert W. McChesney, “The Stagnation of Employment,” Monthly Review, 55, no. 11 (April 2004): 9–11.

- ↩ See John Bellamy Foster, Robert W. McChesney, and R. Jamil Jonna, “The Internationalization of Monopoly Capital,” Monthly Review 63, no. 2 (June 2011): 1–23.

- ↩ Thomas L. Friedman, The World is Flat (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2005). Friedman wrongly claims that his “flat world hypothesis” was first advanced by Marx. See 234–37.

- ↩ Paul Krugman, Pop Internationalism (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1996), 66–67. On the absurdity of expecting wage differences between nations simply to reflect productivity trends see Marx, Capital, vol. 1, (London: Penguin, 1976), 705.

- ↩ On fears of an end to global labor arbitrage see “Moving Back to America,” The Economist, May 12, 2011, http://economist.com.

- ↩ Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 798. Immediately after the quoted passage Marx added the following qualification: “Like all other laws, it is modified in its workings by circumstances, the analysis of which does not concern us here.” It should be added that Marx used “absolute” here in the Hegelian sense, i.e., in terms of abstract.

- ↩ Harry Magdoff and Paul M. Sweezy, Stagnation and the Financial Explosion (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1987), 204. By 2010, OECD unemployment had grown by 38 percent, reaching 48.5 million persons. (“Unemployment, Employment, Labour Force and Population of Working Age [15-64],” OECD.StatExtracts, [OECD, Geneva, 2011], retrieved September 24, 2011.)

- ↩ The concept of “imperialist rent” is developed by Samir Amin in The Law of Worldwide Value (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2011) and is discussed further below.

- ↩ See, for example, the discussion in Anthony Giddens, Capitalism and Modern Social Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971), 55–58. Giddens offers a half-hearted and confused defense of Marx which is full of misconceptions.

- ↩ John Strachey, Contemporary Capitalism, 101; Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 929. Strachey also quotes on the same page the passage from The Communist Manifesto where Marx and Engels write, “The modern labourers…instead of rising with the progress of industry, sinks deeper and deeper below the conditions of existence of his own class. He becomes a pauper, and pauperism develops more rapidly than population and wealth.” Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, The Communist Manifesto (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1964), 23. At first sight this seems to support Strachey’s point (though taken from an early and non-economic work). However, as Hal Draper points out: “This may sound as if the class of proletarians, as such, is inevitably pauperized. This language reflected the socialistic propaganda of the day; later in Capital I (Chap. 25), Marx made clear that the pauper layer is ‘the lowest sediment of the relative surplus population.’” Hal Draper, The Adventures of the Communist Manifesto (Berkeley: Center for Socialist History, 1998), 233.

- ↩ Roman Rosdolsky, The Making of Marx’s ‘Capital’ (London: Pluto Press, 1977), 307.

- ↩ Fredric Jameson, Representing Capital (New York: Verso, 2011), 71.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 799.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 764, 772, 781–94; Marx and Engels, The Communist Manifesto, 7; Paul M. Sweezy, The Theory of Capitalist Development (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1970), 87–92.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 792.

- ↩ Karl Marx, “Wage-Labour and Capital,” in Wage-Labour and Capital/Value, Price and Profit (New York: International Publishers, 1935), 45; Sweezy, The Theory of Capitalist Development, 89.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 763, 776–81, 929.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 794–95; David Harvey, A Companion to Marx’s Capital (London: Verso, 2010), 278, 318.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 795–96.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 590–99, 793–77.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 797–98.

- ↩ Engels deserves credit for having introduced the reserve army concept into Marxian theory, and makes it clear that what demonstrates the reserve-army or relative surplus-population status of workers is the fact that the economy draws them into employment at business cycle peaks. See Frederick Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England (Chicago: Academy Chicago Publishers, 1984), 117–22, and Engels on Capital (New York: International Publishers, 1937), 19.