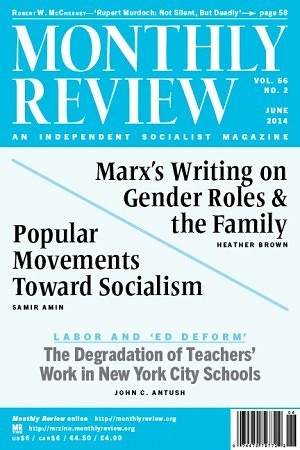

Samir Amin’s Review of the Month in this issue, “Popular Movements Toward Socialism,” offers a masterful analysis of struggles all over the world in the era of what he calls “generalized-monopoly capitalism.” The most important theoretical innovation in his article, in our opinion, is his attempt to bring together a variety of global struggles under the rubric of the “movement toward socialism,” borrowing the terminology from the current practice of a number of South American parties: in Bolivia, Chile, and elsewhere. Movements that fall under this mantle, Amin suggests, may include those that seek to transcend capitalism, as well as others for which the object is more ambiguously a radical upending of labor-capital relations.

In terms of the Latin American parties who are consciously organized around the “movement toward socialism,” he tells us, this generally signifies a shift away from the traditional strategy of Communist parties of seizing the state as a whole and nationalizing the economy. Instead they are engaged in the more patient building up of the political, economic, and social conditions that will allow a real advance toward socialism.

Amin is quite clear that such popular movements toward socialism are not social-democratic movements dedicated to operating within capitalism, but on a kinder, gentler basis. Rather the movements toward socialism are dedicated to radical social change but are confronted with circumstances that hinder the achievement of socialist transformation in the present, and require a strategic reorientation toward a long revolution. Indeed, this characterizes the general nature of socialist struggles today.

To our knowledge, the first clear development of the “movement toward socialism” concept within the Marxian tradition can be attributed to William Morris, as leader of the Socialist League (an organization that included in its leadership Eleanor Marx, and which had Frederick Engels as a supporter). For Morris, in both those cases where subjective conditions of revolution existed but objective conditions were lacking (as in the fourteenth-century Peasant Revolt in England), and in those where objective conditions were present but subjective conditions absent (as in late-nineteenth-century Britain), it was necessary to develop a longer-run revolutionary strategy that emphasized the “movement towards socialism.” As he stated in 1888:

It is not our business merely to wait on circumstances; but to do our best to put forward the movement towards Socialism, which is at least as much part of the essence of the epoch as the necessities of capitalism are. Whatever is gained in convincing people that Socialism is right always, and inevitable at last, and that capitalism in spite of all its present power is merely a noxious obstruction between the world and happiness, will not be lost again, though it may be obscured for a time, even if a new period sets in of prosperity by leaps and bounds. (William Morris, Journalism [Bristol: Thoemmes Press, 1996], 440–41)

Morris was referring here to the possibility that capitalism might be able to revive itself, overcoming its economic stagnation at that time by means of imperialist expansion, particularly the carving up of Africa and other parts of the global periphery—an imperialism which the Socialist League strenuously opposed.

Morris was engaged in a two-front war, trying to steer the Socialist League clear of both the opportunism of some parliamentary socialists and the Blanquist insurrectionism of the cruder anarchist groups of his day. To build socialism, he argued, meant an extended process of organizing, educating, altering base institutions, engaging in strategic class actions, and putting forward a new vision of life rooted in the wellsprings of history—all of which were essential if the working class were to be able to carry out the collective struggle to reconstruct the entire basis of society. The development of the machine industries, he contended in 1890 in his critique of The Fabian Essays in Socialism (the elitist, mechanistic socialism of George Bernard Shaw, Sidney Webb, and others), may contribute to “the movement toward Socialism,” but they are not its “essential condition,” nor for that matter was the instrumentality of the state sufficient; socialism thus could not be achieved by purely mechanical means (William Morris, Political Writings [Bristol: Thoemmes Press, 1994], 460). His overall view of socialist transition was developed most powerfully in the famous chapter, “How the Change Came,” in his utopian romance, News from Nowhere.

A rather astonishing article by Fred Block has come to our attention in which he argues that the concept of “capitalism” should be cast out of left discourse. Block, a professor at the University of California, Davis, has long been considered an important academic figure connected to the U.S. left and is the author of a number of significant books, including Post-Industrial Possibilities (1990) and (with Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward) The Mean Season (1987). In September 1998, he wrote a review of Piven and Cloward for MR.

However, since 2011, Block has taken on the role of a senior fellow at the Breakthrough Institute. Headed by Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger, the Breakthrough Institute is the leading big money, anti-green, pro-nuclear think tank in the United States, dedicated to propagandizing capitalist technological-investment “solutions” to climate change. (See Bill Blackwater, “The Denialism of Progressive Environmentalists,” Monthly Review, June 2012.) Block wrote a 2011 essay, “Daniel Bell’s Prophecy,” for the Breakthrough Institute, helping set up Bell as the primary intellectual figurehead for the Institute—not inappropriate in our view given Bell’s roles as a Cold Warrior (he was associated with the CIA-sponsored Congress for Cultural Freedom) and as an anti-environmentalist (he argued vehemently against the idea that there were ecological limits to capitalist economic growth).

What struck us as requiring a response, however, was Block’s article entitled, “Varieties of What?: Should We Still Be Using the Concept of Capitalism?” (in Political Power and Social Theory [2012], 269–91), where he argued that the concept of capitalism should be abandoned as dysfunctional for the left—to be replaced by Karl Polanyi’s “market society.” Block offered a mixed bag of arguments to justify this position, including: (1) an online Google search found only 21 million hits for the words “occupy wall street” and “capitalism” together and over 800 million for “occupy wall street” by itself, supposedly justifying the conclusion that capitalism was not part of the “main rhetoric” of “the militants in the Occupy Wall Street movement”; (2) the right has taken over the term capitalism and made it their own; (3) “by the last decades of the 19th century it was no longer possible to adhere to Marx and Engels’ initial genetic theory of capitalism” since the state became a major actor in determining the economy; (4) Wallerstein’s “neo-Smithian” world-system theory was designed to analyze a competitive world-market economy and has no real relation to Marx’s “genetic theory”; (5) financialization was most likely due to political (and geopolitical) factors and not the manifestation of a “new type of financial capitalism”; (6) political power could not be inferred from class power; and (7) Polanyi’s theory of market society offered “much greater leverage” on political-economic issues “than the concept of capitalism that we have inherited either from Marxism or market liberalism.”

Space does not allow for an answer to all of this. We would like to state, however, that Block bases his argument on a very one-sided view of Polanyi’s multi-dimensional analysis—a misappropriation of his thought that has become popular among some economic sociologists and political economists who, bowing to the neoliberal era, have long-since retreated from the question of the mode of production and now are concerned merely with the mode of regulation. Although Polanyi’s Great Transformation certainly facilitates this shift in focus, the abandonment of capitalism as a historical and theoretical category was not part of his perspective and is antithetical to his work, which was directed rather at uncovering the myth of market fetishism characterizing neoliberal capitalist ideology (which had already originated in the Vienna of his day)—and which, he argued, would have a destructive influence on society if pursued. Here we recommend as an earlier, more sophisticated view of Polanyi’s work, Maria Szecsi, “Looking Back on The Great Transformation,” Monthly Review 30, no. 8 (January 1979); along with the Polanyian critique of neoliberalism offered by Polanyi’s two daughters: Kari Polanyi-Levitt and Marguerite Mendell, “The Origins of Market Fetishism,” Monthly Review 41, no. 2 (June 1989).

In Ecology Against Capitalism (Monthly Review Press, 2002), MR editor John Bellamy Foster provided a detailed critique of the views propounded by Swiss billionaire Stephen Schmidheiny, then the head of the Business Council for Sustainable Development, for his argument that capitalism offered a solution to the environmental crisis. In June 2013, Schmidheiny was sentenced to eighteen years in prison by the Turin Court of Appeals for knowingly exposing thousands of workers to asbestos in his Italian plants. Daniel Berman, author of the Monthly Review Press book Death on the Job (1978), is organizing a campaign to revoke the honorary degree of “doctorate of humane letters” given to Schmidheiny at Yale for his supposed environmental achievements. Those wishing to provide support for the campaign should contact Daniel Berman at [email protected].

Dr. Selma B. Brody, a longtime reader and supporter of MR, celebrated her one-hundredth birthday last month (May 2). Dr. Brody was an X-ray crystallographer who, with others in the nascent Federation of American Scientists, fought for international control of nuclear energy in the early years of the Cold War. From the time of the Spanish Civil War to the present she has been actively engaged in the politics of social change and a champion of science education. She and MR author Grace Lee Boggs were fellow graduate students at Bryn Mawr, where Brody was of one of the earliest science PhDs. Congratulations on your one hundredth anniversary, Dr. Brody, from your friends at Monthly Review!

Correction: In “A Reply to the Editors,” in the April 2014 issue of MR, on page 52, paragraph 3, line 4: “captured by the regulators” should say “captured by the ‘regulated.’”

Comments are closed.