On the afternoon of November 15, 2013, 150 police officers raided the Colony Arms, a low-income housing complex on Detroit’s East Side. One resident described the scene: “I saw the Department of Correction school bus out there…cop cars with the sirens…some kind of tank blocking the back alley, at least two helicopters doing I don’t know what up there. They set up a HQ in the lobby to run everyone’s name…and the news was all up in there, making a little show of it. The officers had real, real long rifles. It was like the army or something…like an invasion…. Yes, I was scared.”1 A black woman in her sixties was arrested for failure to pay a years-old parking ticket. A black mother, eight months pregnant at the time, was arrested for failing to pay a fine for possession of a nickel bag of marijuana. In all, thirty arrests were made, twenty-one related to parking violations. These arrests yielded a total of zero convictions. The raid occurred on a Friday; all those arrested were released from jail by Monday. The raid was declared a resounding success by the Detroit Police Department (DPD) and all of the city’s major media outlets.

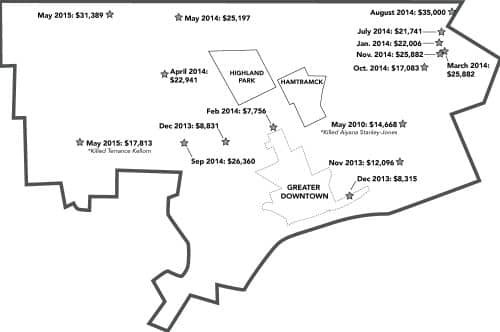

The raid on the Colony Arms inaugurated Operation Restore Order, a series of seventeen paramilitary police operations carried out between 2013 and 2015. Over the course of the operation, police made over a thousand arrests; as in the Colony Arms raid, however, these yielded little in the way of prosecutions. As Wayne County Prosecutor Kym Worthy admitted to the Detroit Metro Times, “our office simply has not received an influx of cases from these raids.”2 The sites of the raids, which chiefly targeted the city’s deeply impoverished West and East Sides, form a jagged perimeter around Greater Downtown, where a disproportionate number of the city’s white residents live, and where upwards of $10 billion has been invested in real estate development in the last decade. (The only raid staged within Greater Downtown took place at the Martin Luther King homes, an affordable housing unit where the median annual household income is just $8,315, around a third of the federal poverty level for families of four.)

Figure 1. SWAT Raids in Detroit, 2013–2015

Although Operation Restore Order ended in 2015, police raids in the city’s peripheral neighborhoods have continued. On July 11, 2016, officers raided an alleged “drug house” on the East Side. According to the residents—a pregnant woman and her fiancé, Durone Sanders—the police did not make their presence known until they shot their way through the front door, killing the couple’s dog and lodging a bullet hole at head-height in the wall of their living room. Sanders told a local news channel that officers with “facemasks and big rifles” then rushed inside, “asking us ‘Who lives here?’ Asking about my tattoos.” After searching the home, the police promptly issued a statement that drugs had been found. Sanders, however, insisted that the police found nothing illegal, a claim corroborated by the fact that no arrests were made, and no tickets related to narcotics were issued.3

A few months later, on September 27, 2016, a team of DPD officers, Michigan State security personnel, and DEA agents raided a West Side home as part of a collaborative “undercover narcotics operation.” According to the Detroit News, “what police believed was a barricaded gunman situation…turned up nothing after they searched a home.” The alleged criminal was not in the house; in fact, a DEA agent involved in the operation admitted that it was unknown whether the suspect had ever been there. A forty-one-year-old disabled woman was, however, present during the raid—and “was safely removed.”4

The geography of these raids follows a larger pattern of uneven development in Detroit. Even as finance capital and real estate investment pour into Greater Downtown, residents of the East and West Sides have endured service cuts, water shutoffs, and the largest foreclosure crisis in U.S. history. And all along, the national news media was positively beaming. The New York Times has heralded the new “Spirit and Promise of Detroit.” The Washington Post proclaimed the city “the greatest turnaround story in American history.” What ideological framework supports such a view?5

There is, first of all, the collective blind faith in the transformative, restorative power of capitalism that characterizes most mainstream media narratives of urban gentrification. Even as the Times acknowledged that “there are no real assurances that gains will be spread democratically across the city, or that city planning and public resources will serve the needs of everyday Detroiters,” it found solace in the vague “hope…that private individuals will keep the greater good in mind.”6

But as I will argue, equally crucial is an ideology that conflates dispossessed and underemployed black people with violent crime, classifying entire communities as security threats. This is the same ideology that framed the Detroit rebellion of 1967 as a lawless riot instead of a political uprising; that legitimated the violent repression of the Black Power movement; that justifies “zero-tolerance” drug laws and mass incarceration; and that has tried to discredit the Black Lives Matter movement.7 In Detroit, after decades of economic decay caused by capital flight and automation, the notion that poor black people represent an inherent threat has hardened into a form of political common sense: the city currently spends $547 per capita on police, while per capita spending on food stamps in Michigan is less than $21.8 The criminalization of those “everyday Detroiters” who stand to benefit least from the “turnaround” is not merely a symptom, but an integral part of the city’s deeply unequal “success story.”

Accumulation by Dispossession

Since 2013, more than 10 percent of Detroit residents, most of them from the East and West Sides, have had their water shut off.9 The average monthly water bill in the city is $75, nearly double the national average. This is partially because the city has spent billions of dollars budgeted for the Water and Sewage Department to repay its creditors, mainly Wall Street banks. According to Al Jazeera, in 2011 “the agency spent $537 million that had been earmarked for repairs paying off interest-rate swaps to major banks.” And though city officials have presented the water shutoffs as a straightforward response to delinquent water bills, the shutoffs evidence a clear pro-business bias. In 2015, residential properties owed the city $26 million in outstanding water bills, compared to $41 million owed by commercial properties; however, residential accounts were four times more likely to be disconnected than commercial accounts.10

In the last decade, more than a third of Detroit homeowners, also disproportionately from the city’s East and West Sides, have lost their homes to foreclosure. Though Michigan law requires municipalities to reassess real estate values every five years, the city of Detroit did not do so once between 1995 and 2015, with the consequence that after the housing crash, as the market value of homes plummeted, Detroiters were still expected to make payments at inflated pre-crash rates. In fact, the city raised interest rates on delinquent tax payments to 18 percent. By 2014, fully 47 percent of Detroit homeowners were underwater on their mortgages. Meanwhile, federal money sent to Michigan to aid struggling homeowners was redirected toward razing abandoned houses: in June 2016, the Michigan state government received $188 million in federal funds as part of the Helping Hardest Hit Homeowners program; just 26 percent went to support homeowners in threat of foreclosure, and the other 74 percent was reserved for “blight removal.”11

The foreclosure crisis has provided fertile ground for a new round of what David Harvey has called “accumulation by dispossession,” updating Marx’s concept of primary accumulation: the purpose of this process, Harvey writes, “is to release a set of assets (including labor power) at very low (and in some cases zero) cost. Overaccumulated capital can seize hold of such assets and immediately turn them to profitable use.”12 The city of Detroit has sold off vast tracts of tax-foreclosed homes, in what the New York Times has called “one of the world’s largest real estate auctions.” The city requires that homes purchased at auction be paid off in full within twenty-four hours, keeping most Detroiters, who tend not to have thousands of dollars in spare cash, from reacquiring their homes. Instead, real estate speculators have pounced: in 2013, twelve buyers bought up more than a hundred homes each, many with the plan to sit on the homes, leaving them vacant as their property value appreciates.13

These policies—water shutoffs, tax foreclosures, and the use of homeowner aid to raze homes—fully align with the recommendations of the Detroit Future City Strategic Framework (DFC), “a blueprint for Detroit’s future” published in 2013, as the city teetered on the brink of fiscal ruin. The DFC, which Mayor Mike Duggan’s chief economic advisor has called his “bible,” is an austerity plan that advocates service cuts and blight removal in the city’s impoverished neighborhoods in order to divert resources toward more “viable” areas. It is, in other words, an attempt to revitalize the city by shifting the costs of its fiscal crisis onto the city’s poorest residents.14

Amid paramilitary police raids, water shutoffs, and mass foreclosures, Detroit, under the direction of state-appointed emergency manager Kevyn Orr, declared bankruptcy. The city’s estimated $18 billion debt made this the largest municipal bankruptcy in history. According to then-mayor David Bing, the roots of Detroit’s fiscal crisis lay in its residents’ “entitlement problem.” Orr agreed: “for a long time,” he lamented, “the city was dumb, lazy, happy, and rich.” At the time of the bankruptcy, Detroit had the highest rates of unemployment and child poverty of any large U.S. city. The city had seen its municipal workforce cut in half since 1990, and since 1992, more than three-fifths of public schools had closed.15

After more than a year of negotiations, the bankruptcy culminated in a new austerity plan: 4.5 percent pension cuts for city employees; an end to cost-of-living increases for retirees; an 89 percent reduction in retirees’ health care plan; and the partial privatization of the Water and Sewage Department. Detroit taxpayers were billed more than $164 million for the services of consultants and lawyers who negotiated the deal.16 Meanwhile, a week after Orr declared bankruptcy, city officials announced that the Detroit public would cover more than half the cost of the Detroit Red Wings’ $450 million new stadium, Little Caesars Arena, to be built in the heart of Greater Downtown. Red Wings owner Mike Ilitch, who also owns the Detroit Tigers and the Little Caesars pizzeria chain, has an estimated net worth of $4.8 billion, and has acquired more than a hundred acres of commercial real estate just north of Downtown. Since the late 1970s, Ilitch’s immense personal reservoir of surplus capital has allowed him to buy up and hoard these properties for decades, in anticipation of lucrative development opportunities. In 2013, with the city desperate for investment, Ilitch decided it was time to cash in. As an added incentive, the city sold Ilitch thirty-nine parcels of land for the Little Caesars Arena and the new “entertainment district” that will surround it—all for just one dollar.17

This is not the only time in recent years that the city has sold a billionaire valuable real estate for virtually nothing. Dan Gilbert, the chairman and founder of Quicken Loans and Rock Ventures, acquired eighty-five buildings in the Greater Downtown between 2007 and 2016; most were sold to him by the city, several of them for a single dollar. Gilbert now effectively owns more than half of downtown Detroit, an area of more than thirteen million square feet.18

Consistent with the broader “success story” of post-crisis Detroit, the mainstream media hailed Gilbert, whose net worth exceeds $5 billion, as the city’s savior: WXYZ Detroit named him “Newsmaker of the Year” in 2013; the Atlantic wondered if he was “Detroit’s New Superhero”; a New York Times headline called him a “Missionary” on a “Quest to Remake Motor City.” The adulation showered down despite the fact that Gilbert had extorted $200 million in additional tax incentives when he threatened to move Quicken Loans corporate headquarters to Cleveland, and presided over a company that, as Ryan Felton of the Metro Times has reported, earned 20 percent of its revenue in the Detroit metropolitan area in 2006 from selling the subprime mortgages that would help bring the city to its knees. In effect, the tax breaks and other subsidies given to Gilbert compelled Detroit residents to subsidize their own foreclosure crisis.19

Meanwhile, as finance capital and real estate money poured in, 14,000 whites moved to the city between 2010 and 2015, increasing Detroit’s white population by 25 percent. The vast majority moved into Greater Downtown: while whites made up 10 percent of Detroit’s population in 2015, they made up 22 percent of the Greater Downtown population. Many are lured by subsidies offered to employees of new businesses who move into Greater Downtown, including up to $20,000 in forgivable loans and $2,500 rent forgiveness.20 Predictably, downtown rents have nearly doubled since 2010, as developers have purchased low-income apartments and converted them into luxury complexes. The result, as in other gentrifying city centers, has been the dislocation of thousands of poor and working-class citizens, most of them nonwhite, many of them lifelong residents of the city.21

Ideologies of a Police State

On August 8, 2014, the day before Michael Brown was killed by police in Ferguson, Missouri, the U.S. Department of Justice agreed to suspend federal oversight of the DPD. The department, which in 2000 led the nation in fatal shootings by police officers, had been under close scrutiny for more than a decade. The Detroit Coalition Against Police Brutality (DCAPB) and other groups criticized the decision, citing Emergency Manager Orr’s claim that it took Detroit police an average of 58 minutes to respond to emergency calls in 2013. DPD has overcompensated for this dysfunction with militarized spectacles of police power: the DCAPB noted that since seven-year-old Aiyana Stanley-Jones was killed by a SWAT officer in a 2010 raid on the East Side, SWAT raids have been deployed ever more widely, even as more immediate community needs go unmet.22 But DPD Chief James Craig defended the deployment of SWAT teams, claiming they were only used in extreme situations: in “fortified locations…where there are heavy armaments, who better to send inside that location to execute a search warrant other than special response teams of SWAT units?…. [W]hen we have to address an active shooter situation or barricaded suspect, I think the community would applaud us coming in with an armored vehicle, not only to keep our officers safe, but to keep our community safe.”23

The seventeen raids that composed Operation Restore Order tell a different story. According to the Metro Times, over the course of the raids, DPD impounded more than 1,000 vehicles, issued nearly 16,000 tickets, confiscated 175 weapons, and commandeered more than $200,000 in cash. Police also seized more than 300 kilograms of narcotics, nearly all of it marijuana, a drug that Detroiters voted to decriminalize in 2012. Far from being deployed only in “active shooter situations” or “fortified locations,” these SWAT operations were effectively little more than low-level weed busts.

Nonetheless, the city’s news outlets lauded Operation Restore Order, depicting the poor black Detroiters targeted in the raids as dangerous criminals, despite the paucity of arrests or prosecutions.24 In its assumption of guilt and its stubborn rejection of reality, the ideology at work here seemed to follow an old totalitarian logic: “the best proof of people’s guilt is the lack of all proof. For if there is no proof, it must be because they have hidden it; and if they have hidden it, then they must be guilty.”25 Throughout Operation Restore Order, whenever no criminal activity was found at the site of a raid, the media parroted the official police line that the best proof that the people targeted were dangerous criminals was the absence of any proof of criminal activity. Here is the transcript of WXYZ Detroit’s report on the operation’s final raid:

Reporter Carlson: The Detroit Police Department is getting good at these organized crackdowns.… On this snowy March morning they were at it again, this time hitting this home, which the Chief says was a drug den.

Commissioner Craig: It was an active narcotics location based on what we’re finding.

Reporter Carlson: But in this case the suspects got away. Could be [that]the bad guys know this is becoming more common.… When the accused drug dealers get home, they’ll find a rude awakening, and a casualty.

Commissioner Craig: There was a large-sized pitbull inside that the SRT officers had to put down. He became aggressive during the entry. They fired two shots.

Reporter Carlson: This was the seventeenth Operation Restore Order. Every now and then the SWAT vehicle rolls into trouble spots in a show of force. It’s to put wrongdoers on notice, and to let residents know the department means business….

Commissioner Craig: This is about making this city safe and we have to sustain it.

Reporter Carlson: And the chief says when he rolls into one of these busts now, the people say we know you were coming, but we didn’t know you were coming today. A sign that the message is getting across.26

Here is the Detroit News on the same operation:

Tuesday’s sweep was a uniformed, zero-tolerance initiative in the department’s Second and Eighth districts. “We will continue to strive for an environment which will allow residents to safely reside within their neighborhoods without the fear of crime,” police said in a statement Tuesday afternoon. Earlier in the day police raided a suspected drug house on the city’s west side as part of the crime sweep. “We hit the location and, unfortunately, it appears the suspects got out before we got in,” Chief James Craig said shortly after the raid.27

When no criminals, drugs, or weapons were found at the location of the raid, Craig assumed that “the suspects got out before we got in.” Reporters presented the lack of any evidence of criminal activity as irrefutable evidence that the “suspects got away,” perhaps with the help of other complicit residents who “tipped off” the criminals. WXYZ’s reporter went so far as to ponder whether the “bad guys” were scared off because they know police raids were “becoming more common.” The only responsible course of action, then, was another round of raids: as Chief Craig said, “we have to sustain” the aggressive policing, lest the criminals resurface and resume their illegal activity scot-free.

This is not to say that there is no “criminal” activity taking place in Detroit, or that all of Operation Restore Order’s raids targeted people who had not violated any laws. But like the Colony Arms residents forced by SWAT officers to have their names run through the police database before they were released, hundreds of thousands of poor Detroiters are presumed guilty before proven innocent, and even then, their innocence is viewed with skepticism.

As to why criminals break the law, no context is given, save the fact that they are criminals. It is as if these raids existed in a Foucauldian nightmare world with only three classes of people: criminals, concerned citizens, and police. In this world, the 39 percent of Detroiters living below the poverty line—the highest percentage among all large U.S. cities—are not victims of an unequal system, but threats to be combatted and contained by the police. This ideology not only legitimates the deep inequality that has characterized Detroit’s “revival,” but depicts the city’s poorest citizens as antagonists and obstacles to this “revival,” and underwrites the austerity measures that cut services to these “criminal” populations. The raids send a potent signal to capital and to the new wave of white young professionals that the state will not allow these criminals to disturb the city’s revitalized commerce.

The dislocation of thousands of residents from Cass Corridor, an area just north of Downtown but now subsumed under the Greater Downtown moniker, has been justified in the same terms. An article in the July 13, 2016, Detroit News, headlined “Revival of Detroit’s Cass Corridor crowds out criminals,” begins in storybook fashion: “In the rebranded Cass Corridor, police say hipsters are crowding out the criminals. But the drug dealers who have permeated the neighborhood for years aren’t going down without a fight.” The report goes on to quote DPD Captain Darin Szilagy: “The revitalization of the Cass Corridor has left very little territory for drug dealers…. The little that’s left has become valuable territory, and that’s led to some violence. You have your OGs (original gangsters) who go back to the 1980s, and they’re fighting with the younger guys who are trying to move in…. This is where these dealers have operated for years, and they want to hold on to it.” Lyke Thompson, Director of Wayne State University’s Center for Urban Studies, offered a more academic but equally unequivocal version of the story: “Gentrification…affects criminals, too…. It’s been happening all over the country…. You see development, and when you have a strong foundation of investment, that brings more law enforcement and people who are more likely to report crimes. And the criminals are forced to go elsewhere.”28

The city’s overwhelmingly black homeless population has likewise been criminalized. According to Mark Jacobs, director of Heart 2 Hart, a Detroit homeless outreach organization, there are around 20,000 homeless people in the city, but only 1,900 shelter beds—enough for only 9.5 percent of the homeless population. Earlier this year, Mayor Duggan promised to reduce the number of people “wandering” and “begging” near Downtown, and a recent investigation by Sarah Mehta of the ACLU details how he intends to keep this promise: homeless people in Greater Downtown are “being approached and harassed by police, not necessarily for anything they’re doing, but just because of the way that they look…. Often they’re being dropped off late at night in neighborhoods that they don’t know. Police often take any money they have out of their pockets and force them to walk back to Detroit, with no guarantee of any safety.”29

The foreclosure crisis and subsequent gentrification have only compounded the deep-seated cause of the city’s homelessness crisis: chronic joblessness. Nearly half of male Detroiters aged 20–64 did not have a job in 2008, and in 2016, even as employment rates recovered nationwide, close to 25 percent of the city’s working-age population remained jobless. But in the absence of any plans for employment, public works, or affordable housing programs, homelessness is treated as a security problem. Nationally, the trend is the same: 21 percent of new arrestees report being homeless on the night prior to their arrest. In Los Angeles, $87 million of the $100 million in the city budget recently devoted to the problem of homelessness was allocated to the police.30 In Detroit, according to Police Chief Anthony Holt, the message from police to panhandlers is clear: “We don’t want you to move from Woodward and Warren to Woodward and Selden. We want you to stop the behavior.” But in the city with the highest urban unemployment rate in the nation, it is unclear what alternatives could allow them to “stop the behavior.”31

DPD’s crackdown on low-level crimes such as loitering and panhandling follows the logic of “broken windows” policing, the now-famous strategy promoted by the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think tank, and first implemented in New York City in the 1990s by Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and Police Commissioner William Bratton. DPD Chief James Craig served under Bratton when he brought broken windows policy to Los Angeles in 2002. In 2013, the city of Detroit paid $600,000 to the Manhattan Institute and undisclosed fees to the Bratton Group for their help facilitating DPD’s own adoption of broken windows tactics.32 According to Ruth Wilson Gilmore and Craig Gilmore, the strategy “aims to remove not only broken windows and graffiti but also the people who are, as Fred Moten puts it, themselves broken windows: those who make others uncomfortable, those who spend too much time in the streets.”33

Liberal discourse tends to frame broken windows as a policing strategy with a commendable track record of reducing crime, but which employs overbearing tactics, such as stop-and-frisk, which lead to undue harassment. But this misses the larger picture. Broken windows policing has little to do with crime reduction; rather, it is the police strategy consonant with a neoliberal state that treats its racialized surplus population as a potential threat to capital accumulation. In Detroit, where such accumulation is perceived as part of a novel and fragile “revival,” this imperative is even stronger. As broken windows has been exported from New York to cities like Baltimore, Detroit, and Los Angeles, this dehumanizing logic has come to dominate daily life in poor communities of color across the country. President-elect Trump’s dog-whistle invocations of “law and order,” his spurious claims that “inner-city” crime has reached “record levels” of unconscionable “slaughter,” as well as his intimate ties to Giuliani, suggest that black and brown Americans will continue to be punished for their poverty by aggressive policing.34

Resisting the Police State

Since its founding in 2013, the Black Lives Matter movement has challenged the legitimacy not only of police tactics, but of the entire structure of criminal justice in the United States. The significance of this movement cannot be understood unless the intensity and violence of day-to-day encounters between police and poor people of color is fully appreciated. In the United States, a black person is killed by police every twenty-eight hours.35

State violence toward black people is of course nothing new. What is “qualitatively new” about the post-civil rights era, as Manning Marable presciently observed in How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America, is that millions of black workers, previously employed in the agricultural and industrial sectors, have been rendered superfluous to capital, primarily due to automation, monopolization, and globalization—changes that have hit Detroit, once the great workshop of U.S. manufacturing, with special force.36 Between 1950 and 2012, the share of manufacturing in U.S. GDP declined from 28 percent to 12 percent. This decline is inextricably linked to processes of primary accumulation that have provided capital with cheaper, more docile sources of labor the world over: since 1980, the global proletariat has increased by more than one billion workers, and between 1980 and 2008, the global South’s share of the world’s industrial employment increased from 51 percent to 73 percent. Black workers, who were at the vanguard of the labor movement in the 1960s and ’70s, and whose vulnerable structural position in the U.S. economy made them “last to be hired, first to be fired,” have been hit hardest by the decline in manufacturing jobs. At present, the black unemployment rate is nearly double the rate for whites, and more than one in five young black workers is without a job.37

Contemporaneous with these economic shifts, the U.S. government has instituted a historically unprecedented regime of mass incarceration. In 1965, 780,000 people in the United States were in prison or jail, or on probation or parole. By 2010, that number was 7 million. The carceral state targeted the same sectors of the working class hurt most by economic dislocation: poor people of color. As Loïc Wacquant has noted, “fewer than half of the inmates [in U.S. prisons] held a full-time job at the time of their arraignment and two-thirds issue from households with an annual income amounting to less than half of the so-called poverty line.” Blacks and Hispanics comprise 58 percent of the prison population though they account for only one-fourth of the general population. What these figures reveal is that mass incarceration, like broken windows policing, has primarily targeted the country’s racialized surplus population.38

Trends in public spending further show the extent to which the U.S. government has treated poverty in black and brown communities as, above all, problems of security. In the last half-century, penal expenditure as a percentage of total U.S. non-defense public spending has nearly doubled. And since 1982, spending on police has increased by 445 percent. Much of this has gone towards the “militarization” of U.S. police forces, which now spend more than $400 million each year on military-grade equipment, compared to $1 million in 1990. Equipped with armored vehicles, assault rifles, drones, and more, police forces have accordingly launched more military-style operations. SWAT raids, which target black Americans 40 times more frequently than they do white Americans, have increased in frequency from 3,000 a year in the early 1980s to 50,000 in recent years. Urban military operations began as the state’s authoritarian response to black working-class resistance to economic injustice and police violence: the first SWAT operation was a raid on the Los Angeles headquarters of the Black Panther Party in 1969, during which officers fired off 5,000 rounds of ammunition and detonated dynamite on the roof of the building so as to attack the Panthers from above. Today, however, SWAT teams have become routine in poor black and brown communities, mostly deployed for “drug searches”—which in at least one third of cases yield no drugs.39

All this helps to situate the recent claim made by Patrisse Cullors, a cofounder of Black Lives Matter: “the police have become judge, juror and executioner. They’ve become the social worker. They’ve become the mental health clinician. They’ve become anything and everything that has to do with the everyday life of mostly black and brown poor people.” Leading the movement to resist the authoritarian role of police in poor communities of color, Black Lives Matter has organized protests across the country, many involving clashes between protesters and paramilitary police officers equipped with riot gear. President Obama condemned the violent uprisings in Baltimore and other cities as the actions of “criminals.” Thus even black people’s resistance to criminalization has been criminalized.

Private Policing

As Robin D. G. Kelley has written, “those targeted by the state are not rights-bearing individuals to be protected but criminals poised to violate the law who thus require vigilant watch—not unlike prisoners.” Such vigilance, it should be noted, is not limited to state forces. In 2010, there were around one million private security guards employed in the United States, and it is estimated that the number of guards will increase to 1.2 million by 2020. These private security forces have not replaced police so much as collaborated with them and amplified their power. Nowhere is this private-public partnership more evident than in Detroit.40

Downtown, Dan Gilbert employs private security guards from Guardsmark Inc., “trained to spot potential trouble and to deter thieves, drug dealers, muggers and even aggressive panhandlers.” These guards are under no legal obligation to read detainees their Miranda rights; they do, however, have the right to use force when apprehending criminals. Detroit police officers are in radio communication with Gilbert’s guards, and they work in tandem to remove unwanted people from the Greater Downtown area.41 Gilbert has also installed a multi-million dollar surveillance system of over three hundred cameras that captures most of what happens in Downtown. And all of it is seen by Gilbert’s security staff, who monitor the live feeds twenty-four hours a day from a Downtown “command center.” DPD has access to Gilbert’s private panopticon, and can use his cameras to surveil major events, such as last summer’s Black Lives Matter protests.42 In 2015, Motor City Muckraker reported that Gilbert’s surveillance team had been illegally installing cameras throughout Downtown, on buildings that Gilbert did not even own. Though Gilbert responded by calling his critics “lying venom filled wannabes” and “dirty scum,” the story was corroborated by several local business owners.43

In 2014, Gilbert raved to the New York Times about Detroit’s endless potential: “here, man, oh, man, it’s a dream. Anything can be created in Detroit.” Unfortunately, the limitations of the current neoliberal imaginary mean that “anything” consists of more and harsher austerity; refurbishing office towers for transnational investors; building tax-subsidized stadiums, luxury apartments, and retail space; and aggressively policing the hundreds of thousands of poor Detroiters who are seen as obstacles to the city’s “revitalization.”44 The ultimate aspiration of these projects is not a just, equal, and prosperous city for all, but, as the Times reported, the hope that Gilbert’s entrepreneurial success will be emulated by a cadre of “mini-Gilberts” and “black Dan Gilberts.”

Meanwhile, manufacturing and municipal jobs continue to disappear from Detroit. As of 2013, only two auto factories remained in the Motor City, and the ratio of automotive jobs to police officers was less than three to one. Detroit has no place for its growing surplus population except ever further on the fringes of its society and economy, and no plan for them except more austerity, criminalization, and repression.45

Notes

- ↩Darren Reese-Brown and Mark Jay, “One Day in November,” Berkeley Journal of Sociology 58 (2014): 24. The author would like to thank Philip Conklin, Kevin Chamow, Raihan Ahmed, Chris McAuley, Salvador Rangel, Jamella Gow, David Feldman, Darren Reese-Brown, and Kelvin Parker-Bell; without their insights and support, this piece would not have been possible.

- ↩Ryan Felton, “Operation: Restore Public Relations,” Detroit Metro Times, April 15, 2015.

- ↩Hannah Saunders, “Detroit man says police killed his dog raiding house for suspect not there,” Fox 2 Detroit, July 12, 2016.

- ↩Candice Williams, “Police conduct drug raid on west side,” Detroit News, September 27, 2016.

- ↩Frank Bruni, “The Spirit and Promise of Detroit,” New York Times, September 9, 2015; Matt McFarland, “What will be the greatest turnaround story in American history? This author says Detroit,” Washington Post, July 8, 2014.

- ↩Ben Austen, “The Post-Post-Apocalyptic Detroit,” New York Times Magazine, July 11, 2014.

- ↩See the insightful work of Jordan T. Camp in Incarcerating the Crisis (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2016).

- ↩Richie Bernardo, “2016’s Cities with the Best and Worst ROI on Police Spending,” WalletHub, December 17, 2015, http://wallethub.com; Erika Rawes, “7 States with the Most People on Food Stamps,” Cheat Sheet, June 19, 2016, http://cheatsheet.com.

- ↩Aboyomi Azikiwe, “The Privatization of Water in Detroit: Massive Water-Shutoffs,” Global Research, April 26, 2016, http://globalresearch.ca; Joel Kurth, “Detroit hits residents on water shut-offs as businesses slide,” Detroit News, April 1, 2016.

- ↩Laura Gottesdiener, “UN officials ‘shocked’ by Detroit’s mass water shutoffs,” Al Jazeera America, October 20, 2014, http://america.aljazeera.com.

- ↩Joel Kurth and Christine MacDonald, “Volume of abandoned homes ‘absolutely terrifying,’” Detroit News, May 14, 2015; Ryan Felton, “Redefining eminent domain,” Detroit Metro Times, May 13, 2014; “Demonstration—Stop Foreclosures & Water Shutoffs,” Moratorium NOW!, June 14, 2016, http://moratorium-mi.org.

- ↩David Harvey, The New Imperialism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 149.

- ↩Austen, “The Post-Post-Apocalyptic Detroit.”

- ↩Bill McGraw, “Resigning Detroit: Mayor Mike Duggan’s blueprint unveiled,” MLive, August 18, 2015, http://mlive.com.

- ↩Aaron Petkov, “Detroit’s Grand Bargain,” Jacobin, June 30, 2014; Thomas J. Sugrue, “The Rise and Fall of Detroit’s Middle Class,” New Yorker News Desk blog, July 22, 2013, http://newyorker.com; Diane Bukowski, “Genocidal Snyder/Rhodes Plan Harms Detroit,” Voice of Detroit, May 6, 2016, http://voiceofdetroit.net.

- ↩Christine Ferretti, “For Detroit retirees, pension cuts become reality,” Detroit News, February 27, 2015; Christine Ferretti and Robert Snell, “Detroit bankruptcy fees top $170M,” Detroit News, December 31, 2014.

- ↩Bill Bradley, “Detroit Scam City: How the Red Wings Took Hockeytown for All It Had,” Deadspin, March 3, 2014, http://deadspin.com.

- ↩Louis Aguilar, “Putting a price tag on properties linked to Gilbert,” Detroit News, April 29, 2016; Christina Cannon, “Detroit’s Downtown Revival, Led by Dan Gilbert,” ReBusiness, May 19, 2016, http://rebusinessonline.com.

- ↩“WXYZ-TV chooses Detroit businessman Dan Gilbert as ‘Newsmaker of the Year,’” WXYZ Detroit, February 21, 2013; Tim Alberta, “Is Dan Gilbert Detroit’s New Superhero?” The Atlantic, February 27, 2014; David Segal, “A Missionary’s Quest to Remake Motor City,” New York Times, April 13, 2013; Ryan Felton, “What kind of track records do Quicken Loans and Dan Gilbert have in Detroit?” Detroit Metro Times, November 12, 2014.

- ↩Louis Aguilar and Christine MacDonald, “Detroit’s white population up after decades of decline,” Detroit News, September 17, 2015; Regina Bell, Jela Ellerfson, and Phil Rivera, 7.2 SQ MI: A Report on Greater Downtown Detroit, second ed. (Detroit: Hudson-Webber Foundation, 2015), 72, http://detroitsevenpointtwo.com.

- ↩Louis Aguilar, “Ilitches bet big on land near MotorCity Casino,” Detroit News, August 26, 2015; Abayomi Azikiwe, “Privatizing Detroit: Residents Evicted and Displaced by Corporate Interests,” Global Research, April 30, 2013.

- ↩Mike Wilkinson, “Tracking progress in Detroit police response times a fool’s errand,” Bridge, November 10, 2015, http://bridgemi.com.

- ↩Niraj Warikioo, “Detroit Chief: Comparing city to Ferguson is ‘appalling,’” USA Today, August 19, 2014.

- ↩Felton, “Operation: Restore Public Relations.”

- ↩Quoted in Nikos Poulantzas, State, Power, Socialism (London: Verso), 2014, 46.

- ↩Jonathan Carlson, “Detroit Police Department’s crackdown on drug dens results in arrests seizures,” WXYZ Detroit, March 3, 2015.

- ↩Holly Fournier, “15 arrests, 92 citations during west side police raid,” Detroit News, March 3, 2015.

- ↩George Hunter, “Revival of Detroit’s Cass Corridor crowds out criminals,” Detroit News, July 13, 2016.

- ↩Mark Jacobs, “Officials Turn Blind Eye to Detroit’s Growing Homeless Crisis,” Deadline Detroit, June 3, 2013, http://deadlinedetroit.com; Bill Laitner, “Count of homeless Americans hits Detroit streets,” Detroit Free Press, February 1, 2016; “ACLU Urges Detroit to End Illegal Practice of ‘Dumping’ Homeless People Outside City Limits, Files DOJ Complaint,” ACLU, April 18, 2013; “ACLU: Detroit Police Dumping Homeless Outside City,” CBS Detroit, April 18, 2013.

- ↩“Detroit’s Unemployment Rate Is Nearly 50%, According to the Detroit News,” Huffington Post, May 25, 2011, http://huffingtonpost.com; Greg A. Greenberg and Robert A. Rosenheck, “Jail Incarceration, Homelessness, and Mental Health: A National Study,” Psychiatric Services 59 (2008), 170–77; Jordan T. Camp and Christina Heatherton, eds., Policing the Planet (London: Verso, 2016), 4.

- ↩Jon Zemke, “Greater Downtown Detroit Volunteers Work to Improve Public Safety, Quality of Life,” Huffington Post, May 22, 2012.

- ↩“Detroit Police Hire Architects of NYPD’s Unconstitutional Stop-and-Frisk Program,” ACLU, April 24, 2014.

- ↩Ruth Wilson Gilmore and Craig Gilmore, “Restating the Obvious,” in Michael Sorkin, ed., Indefensible Space (New York: Routledge, 2008), 155.

- ↩Louis Jacobson, “Donald Trump is wrong that ‘inner-city crime is reaching record levels,'” Politifact, August 30, 2016, http://politifact.com.

- ↩Justin Hansford, “Community Policing Reconsidered: From Ferguson to Baltimore,” in Camp and Heatherton, eds., Policing the Planet, 216.

- ↩Manning Marable, How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America (Boston: South End, 1983), 252–53.

- ↩John Bellamy Foster and Robert W. McChesney, The Endless Crisis (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2012), 154, 128; Sonari Glinton, “Unemployment May Be Dropping but It’s Still Twice As High For Blacks,” NPR, February 5, 2016; “Economic News Release: Employment Situation,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, December 2, 2016.

- ↩Naomi Murakawa, The First Civil Right (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 5; Hannah Holleman, Robert W. McChesney, John Bellamy Foster, and R. Jamil Jonna, “The Penal State in an Age of Crisis,” Monthly Review 61, no. 2 (June 2009): 1–17; Loïc Wacquant, “Forum,” in Glenn C. Loury et al., Race, Incarceration, and American Values (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), 60; “Criminal Justice Fact Sheet,” NAACP, http://naacp.org, accessed October 4, 2016.

- ↩Holleman et al., “The Penal State in an Age of Crisis”; Justice Policy Institute, Rethinking the Blues: How We Police in the U.S. and at What Cost (Washington, D.C.: Justice Policy Institute, 2012), 1, http://justicepolicy.org; “How America’s police became so heavily armed,” The Economist Explains blog, May 18, 2015, http://economist.com; Nadia Prupis, “Protest Targets Expo ‘Spreading War on Our Communities,’” Common Dreams, September 9, 2016, http://commondreams.org; Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Black Against Empire (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2013), 223; ACLU, War Comes Home: The Excessive Militarization of American Police (New York: ACLU, 2014), 31–34.

- ↩Robin D. G. Kelley, “Thug Nation: On State Violence and Disposability,” in Camp and Heatherton, eds., Policing the Planet, 28–29; Heather Ann Thompson, “Rescuing America’s Inner Cities? Detroit and the Perils of Private Policing,” Huffington Post, August 25, 2014.

- ↩Heather Ann Thompson, “Rescuing America’s Inner Cities?”; Doron Levin, “Dan Gilbert Has Another New Idea for Downtown: Cycling Security Guards,” Deadline Detroit, November 11, 2012.

- ↩Lauren Ann Davies, “A First Look Inside Dan Gilbert’s Multimillion-Dollar Security Hub,” Deadline Detroit, October 11, 2013; Niraj Warikoo, “Hundreds rally for Black Lives in downtown Detroit’s Campus Martius,” Detroit Free Press, July 9, 2016.

- ↩Steve Neavling, “Dan Gilbert’s team trespasses, installs cameras on downtown buildings without permission,” Motor City Muckraker, February 23, 2015, http://motorcitymuckraker.com; Ian Thibodeau, “Dan Gilbert loses cool, calls report on Bedrock security cameras in Detroit ‘libelous,'” MLive, April 27, 2015; Steve Neavling, “Dan Gilbert’s surveillance team messes with wrong Detroit institution,” Motor City Muckraker, April 26, 2015.

- ↩Austen, “The Post-Post-Apocalyptic Detroit.”

- ↩Brad Plumer, “We saved the automakers. How come that didn’t save Detroit?” Washington Post Wonkblog, July 19, 2013. For a discussion of the relationship between broken windows policing and transnational capital accumulation, see Camp and Heatherton, eds., Policing the Planet, and William Robinson, Global Capitalism and the Crisis of Humanity (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Comments are closed.