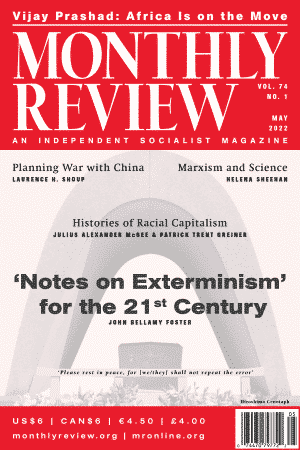

As we write these notes in late March 2022, the war in Ukraine continues to escalate, threatening to mutate instantaneously into a global thermonuclear war, which would result in the extermination of virtually the entire population of the earth. The nature of the current nuclear war threat and how it has reemerged in our time is the subject of the Review of Month by John Bellamy Foster in this issue, titled “‘Notes on Exterminism’ for the Twenty-First-Century Ecology and Peace Movements.”

To get a firm grasp on the current situation in Ukraine, we must understand the central role that the United States and NATO have played in the conflict from the start, beginning in 2014 with the U.S.-engineered Maidan coup. This was followed by the breaking apart of Ukraine, during which the Russian-speaking Crimea was incorporated into Russia after obtaining the population’s support in a referendum, while a civil war emerged between Kyiv, supported by the United States, and the breakaway republics in Russian-speaking Donbass in the eastern part of Ukraine, supported by Russia. Following eight years of civil war—which was again escalating in late 2021 and early 2022, with massive increases in military support and training from the United States and continued attacks by Kyiv on Donbass, in violation of the 2014 Minsk agreements—Russia entered directly into the civil war, transforming it into a full-scale war, with further horrendous results. This brought to the fore the reality that what was being played out in Ukraine was not simply a civil war between Kyiv and Donbass, which has set the stage, but rather a much larger proxy war between the United States/NATO and Russia, which has been developing for decades and lies at the root of the conflict.

As Leon Panetta, former director of the CIA (2009–11) and secretary of defense (2011-–13) under the Barack Obama administration, declared in mid–March with regard to Washington’s role in the war:

The only way to basically deal with Putin right now is to double down ourselves. Which means to provide as much military aid as necessary to the Ukrainians so that they can continue the battle against the Russians.… We are engaged in a conflict here. It is a proxy war with Russia whether we say so or not. That effectively is what is going on. And for that reason, we have to be sure we are providing as much weaponry as possible.… Make no mistake about it, diplomacy is going nowhere unless we have leverage. And the way you get leverage is by frankly going in and killing Russians. That is what the Ukrainians have to do. We have to continue the war effort.… Because this is a power game. (“U.S. Is in a Proxy War with Russia,” Bloomberg, March 17, 2022)

At the center of Panetta’s declaration here is the acknowledgment that the United States is engaged in a protracted “proxy war” with Russia, to be fought in Ukraine, with the Kyiv military forces serving as a Western proxy in a larger geopolitical struggle. The U.S./NATO role in this view is one of “providing as much weaponry as possible,” escalating the war rather than seeking diplomatic solutions.

A proxy war, in the influential definition offered by political-military strategist Andrew Mumford in 2013, is a conflict “in which a third party intervenes indirectly in order to influence the strategic outcome in favour of its preferred faction,” with the dominant third party invariably pursuing its own objectives independent of its proxy. Proxy wars are especially favored in conflicts between great powers but are often also used to achieve imperialist ends. In the case of the struggle in Ukraine, as former special advisor to the secretary of defense Colonel Douglas MacGregor has pointed out: “It looks more and more as though Ukrainians are almost incidental to the operation in the sense that they are there to impale themselves on the Russian army and die in great numbers, because the real goal of this entire thing is the destruction of the Russian state and Vladimir Putin.” Of course, the dire consequences of promoting a proxy war in Ukraine extend beyond the military to the civilian population as well (Andrew Mumford, “Proxy Warfare and the Future of Combat,” The RUSI Journal 158, no. 2 [2013]: 40; Alex Rubenstein, “U.S. and NATO Allies Arm Neo-Nazis in Ukraine as Foreign Policy Elites Yearn for Afghan-Style Insurgency,” Internationalist 360°, March 20, 2022).

The U.S. proxy war in Ukraine commenced, as indicated, with the 2014 Maidan coup directed from Washington. Eight years of civil war between Kyiv and Donbass followed (briefly interrupted by the Minsk Agreements), resulting initially in the loss of some 14,000 lives. In February 2022, 130,000 Ukrainian (Kyiv) troops were on the borders of the two Donbass breakaway republics of Donetsk and Luhansk, firing into the region, where the population had already been forced to live for years in a network of underground bomb shelters (Jeremy Kuzmarov, “CIA Director William F. Burns—CAPO of World’s Biggest Spreader of Lies and Misinformation—Is Spreading the Lie that Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine Was Unprovoked,” Covert Action Magazine, March 17, 2022).

In the more than two decades from 1991 to 2014, the United States provided Kyiv with about $3.8 billion in military aid. From 2014 to 2021, direct military assistance to Kyiv was $2.4 billion, including increasingly advanced and lethal weaponry. Military assistance escalated still further with the beginning of the Joe Biden administration in 2021. Already during the Obama administration, the CIA began training Ukrainian counterinsurgency forces to fight Russians, extending this to the Azov Battalion and other neo-Nazi military groupings in Ukraine. The United Kingdom and Canada together have trained 55,000 Ukrainian troops. In November 2021, the Biden administration set up a new U.S.-Ukraine Charter on Strategic Partnership, which explicitly reiterated the goal of bringing Ukraine into NATO and set up the terms of further military support for Ukraine that would effectively promote that objective, thereby crossing red lines that Russia had established with respect to its own security. The full-scale war that broke out in late February due to the Russian intervention led to a massive pouring of weapons into Ukraine and the European theater. Thirty-two nations, almost all of them part of the NATO alliance, have provided or have promised to provide military aid to Kyiv, with billions of dollars in arms flowing into the country to feed an indefinite war (United Kingdom House of Commons, UK Military Assistance to Ukraine 2014–2021, 6–9; Rubinstein, “U.S. and NATO Allies”; “CIA Trained Ukrainian Paramilitaries,” Yahoo News, January 13, 2022; U.S. Department of State, U.S.-Ukraine Charter on Strategic Partnership, November 10, 2021).

The possibility of a diplomatic solution to the conflict is currently being strongly opposed by Washington. In these circumstances, the proxy war, which on the U.S./NATO side is clearly aimed at fatally weakening if not destroying the Russian state, will likely continue, devastating Ukraine and imperiling all of humanity. It follows that all parties to the present conflict, and the world as a whole, need to focus on promoting the conditions of lasting peace through diplomacy, which requires that the vital security interests of all of the regional players be respected. Nevertheless, it is important to remind ourselves that this is an intercapitalist war with all the dangers that such a situation portends. The long struggle for world peace requires a shift to socialism (James Politi, “U.S. Dampens Hopes for Diplomatic Solution to Ukraine Crisis with Russia,” February 14, 2022; James Politi, “U.S. Pours Cold Water on Hopes of Diplomatic Solution in Ukraine,” Financial Times, March 17, 2022).

Aijaz Ahmed, born in 1941, died on March 9, 2022. One of the great Marxist literary figures of our time, a leading social theorist in India and the world, and a Monthly Review and Monthly Review Press author, Ahmed published his masterpiece In Theory: Classes, Nations, Literatures in 1994. This work, consisting of a number of essays, was a powerful critique of the postmodernism, excessive textualism, and the retreat from revolutionary commitment that had emerged, particularly among the French left. In 1997, Ahmad contributed two powerful essays for In Defense of History: Marxism and the Postmodern Agenda, edited by Ellen Meiksins Wood and John Bellamy Foster. For a moving testimonial on Ahmed and his career see Vijay Prashad, “The Life of a Great Marxist: Aijaz Ahmed (1941–2022),” Newsclick, March 10, 2022.

Longtime friend of Monthly Review, Peter Marcuse died on March 4, at age 93. He was the older son of Sophie Wertheim and the Marxist philosopher Herbert Marcuse. He was well known for his critical work in urban planning at the University of California, Los Angeles, and then Columbia. Marcuse contributed numerous times over the years to Monthly Review and Monthly Review Press. In 1991, he wrote the book Missing Marx: A Personal and Political Journal of a Year in East Germany, 1989–1990. For more information, see the memorial statement on his blog, pmarcuse.wordpress.com.

Leo Marx, one of the great cultural historians of the late twentieth century and a Monthly Review author, died on March 10, at age 102. His great 1964 work The Machine in the Garden: The Pastoral Ideal in America, addressing how U.S. cultural figures had responded to urbanization and the destruction of the rural environment, was to exert an enormous influence on the field of American Studies and helped shape ecological thought in the United States. Marx wrote two landmark essays for Monthly Review: “Notes on the Culture of the New Capitalism” (July 1959) and “Double Consciousness of the Cultural Politics of F. O. Matthiessen” (February 1983).

Comments are closed.