A medical team is considered good by the hospital if it makes profits; otherwise, it will be regarded as not good. Are they people’s hospitals?

Despite spikes in COVID-related deaths in December 2022 and January 2023, following Beijing’s lifting of its “zero-COVID” restrictions, China’s fight against the pandemic over the past three years has compared favorably with that of all other major world economies. The key to this achievement is the country’s unique governance system, including, but not limited to, the leadership of the Communist Party of China (CPC), the functioning of the state-owned enterprises, and the effective mobilization of the masses. Specifically, in battling against the pandemic, the CPC has demonstrated a solid organizational capacity when deploying its material resources, health care workforce, and volunteers nationwide. At a time when supply chains were disrupted, China’s state-owned manufacturing firms quickly converted their factory lines to making medical equipment and supplies. The relatively high level of civil compliance (mainly owing to trust in the government) has ensured smooth implementation of non-pharmaceutical interventions (such as quarantine, social distancing, mask-wearing, and enrolling in national contact tracing).1 China’s response to COVID-19 largely parallels its successful anti-schistosomiasis experience in the 1950s. As Chairman Mao Zedong famously concluded in the postscript of his 1956 poem, “Farewell to the God of Plague,” “with the joint efforts of the Party, the scientists, and the masses, the God of Plague (schistosomiasis) can only run away.”2

Although China’s health system has functioned efficiently during the COVID-19 pandemic with timely and free deliveries of tests, vaccines, and treatments, outside of the pandemic, the system has not always performed optimally. Despite growing government spending on health, the household burden of out-of-pocket health care costs has increased. Self-rated health scores among the population have decreased and chronic disease prevalence has increased, especially for young people. Unnecessary medical care remains widespread, and the patient-physician relationship has not yet achieved a satisfactory level. While China’s health and health care in the “New Era” have seen significant improvements, they face deep-seated problems and challenges.

The Pendulum Swing of China’s Health System: A Brief History (1949–2012)

Medicine is extensively embedded in each country’s political economy. When China emulated the Soviet model in the early 1950s, the country’s health system was attuned to serve fast industrialization, leading to an urban bias. For example, in 1951, the government established labor health insurance exclusively for urban industrial workers, while the health of rural farmers, who constituted 90 percent of the population, was left unattended.3 This urban bias was rectified in the 1960s. Having led China through three years of natural calamities and famine (1959–61), during which total grain output decreased by nearly 30 percent, Mao took steps to balance the development between agriculture and industry.4 To advance agricultural production, health policies and medical resources were tilted toward the rural sector. Following Mao’s directive in 1965 that “in medical and health work, we should focus on the countryside,” the Rural Cooperative Medical System was established and financed by commune (township) or brigade (village) welfare funds.5 So-called barefoot doctors (local paramedics), elected by collective members on the basis of their proven willingness to serve the people, rather than educational credentials, delivered most health services.

The achievements generated from the transformation were unprecedented. Between 1965 and 1975, China’s life expectancy at birth leaped from 49.5 to 63.9 years, and the child mortality rate (under 5 years old) was reduced from 210 to 100 per 1,000 live births.6 Such progress dwarfed most countries with the same or better economic conditions at the time. Also during this period, hospital beds per one million people in rural China more than doubled, from 510 to 1,230, and the urban-rural ratio halved, from 7.40 to 3.75.7 At the 1978 International Conference on Primary Health Care held in Alma-Ata, the World Health Organization (WHO) hailed China’s rural health system as a model for other developing countries to follow.8

Nevertheless, the economic reform in the late 1970s significantly shifted the trajectory of China’s health and health care. In the rural sector, the collective economy collapsed within a brief period (though the land remained collectively owned), ending the Rural Cooperative Medical System and barefoot doctor program. Patriotic health campaigns that previously had engaged rural dwellers in improving environmental sanitation and hygiene also wound down. As recognized in a 1981 official report, the lack of doctors and medication re-emerged in the Chinese countryside.9 Meanwhile, in cities, the marketization of state-owned enterprises in the 1990s led to a significant decline in government subsidies for worker welfare, including their health benefits. Public health institutions for disease control and prevention also experienced financial disruptions.

The health consequences of these institutional changes were severe. In the last two decades of the twentieth century, life expectancy increased by less than five years (from 66.8 to 71.4), which was out of step with comparable countries.10 This slow progress was especially worrisome given China’s relatively rapid economic growth during that period. At the dawn of the twenty-first century, schistosomiasis epidemics, which had been well-controlled under the Mao era, bounced back. A news investigation revealed that, to survive financially, local centers for schistosomiasis control shifted their focus from disease prevention to treatment and selling liver-protecting drugs.11 By the early 2000s, only about 25 percent of the Chinese population (50 percent of urban and 10 percent of rural residents) had some health protection. The overwhelming majority were not covered by any insurance scheme and had to pay out of pocket.12 The WHO ranked China 188 out of 191 countries for “fairness in financial contribution.”13

The government was fully aware of the problems. In 2005, the Development Research Center of the State Council, a high-profile government think tank, recognized that China’s market reform in the health sector was “unsuccessful.”14 This was the first time in China that an official agency had openly acknowledged the failure of market reform measures. In fact, in addition to problems with its health care, China in the early twenty-first century was plunged into unprecedented challenges, brought about by drastic social and economic changes such as mass layoffs at state-owned enterprises and rural land marketization.15 Rampant protests by laid-off workers and rural farmers moved the country from political stability to an “extremely grave” situation.16

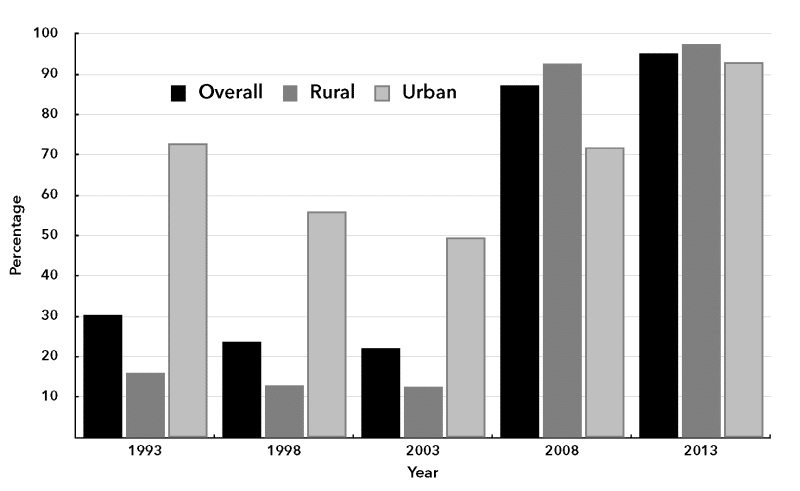

To restore social cohesion, the government in the 2000s implemented a series of social welfare policies, including extending urban insurance coverage and establishing a new health insurance scheme for farmers.17 These efforts proved remarkably effective. Within a decade, government health insurance coverage in China jumped from 22.1 percent to 95.1 percent (see Chart 1). Progress was especially noteworthy in the rural sector, where health insurance coverage jumped from 12.6 percent in 2003 to 97.3 percent in 2013. Government spending on health significantly increased in both absolute terms and as a percentage of total health expenditure. Yet prevailing market forces continued to undermine China’s health system, posing severe health threats for the ensuing decade.

Chart 1. Health Insurance Coverage in China, 1993–2013, Percent of Population

Source: Center for Health Statistics and Information, National Health and Family Planning Commission, An Analysis Report of National Health Services Survey in China 2013 (Beijing: China Union Medical College Press, 2015), 21.

China’s Health and Health Care in the “New Era”

Since 2012, China has “crossed a threshold into a new era.”18 As President Xi Jinping stated, China had experienced “a historic rise from standing up (1949–76), growing rich (1978–2012), to getting strong (2012 onwards),” and “the time had come to enact a new era of socialist modernization and satisfy the people’s need for a better life.”19 Under Xi’s core leadership, the country’s health and health care trends have been characterized by both achievements and challenges. These trends are examined in this section in an analysis of data from two primary sources: the China Health Statistics Yearbook from multiple years and the latest two waves of the National Health Services Survey (2013, 2018). To save space, references from these sources are not repeatedly cited in the text, but data from other sources are noted. Whenever possible, I use the latest available data. However, for indicators that might have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic since 2020 (such as health spending resources), I show only statistics through 2019.

Achievements

Between 2012 and 2021, China’s infant mortality rate fell by half, from 10.6 to 5.0 per 1,000 live births, and life expectancy from birth increased to 78.2 years.20 During the COVID-19 outbreak, both indicators compared favorably to those of the United States, whose health performance has been traumatized by the epidemic. By and large, China’s progress in health indicators can be attributed to a sustained government commitment to increase the health budget and further expand both medical insurance coverage and access to medical resources.

For example, between 2012 and 2019, government annual health spending per capita almost doubled, from $167.74 to $304.16 (in constant 2015 USD), and its share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased from 2.53 percent to 3 percent. Accordingly, during this period, hospital beds per 1,000 people increased by 48.6 percent, from 4.24 to 6.3, and health care workers per 1,000 people increased by 36.7 percent, from 5.3 to 7.3. Between 2013 and 2018, health insurance coverage expanded from 95.6 percent of the population to 97.1 percent. Also, the percentage of households within a 15-minute travel distance from the nearest medical institution increased from 83 percent to 89.9 percent, and pregnant women having five or more prenatal examinations rose from 69.1 percent to 88 percent.

Particularly laudatory is that a “social determinants of health” perspective, which understands health or the lack of it as the combined outcome of economic, societal, and political factors, has been introduced into health governance. In August 2016, Xi presided over the National Health Meeting that recognized the health of the masses as the nation’s strategic priority.21 Richard Horton, the Lancet‘s Editor-in-Chief, praised the move as “a far-reaching plan to make health the overriding goal of economic growth and political reform.”22 At the meeting, Xi introduced the concept of “big health” (da jiankang), calling for shifting policy focus from treating illnesses to enhancing people’s overall health. Later that month, the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee passed the Outline of the Healthy China 2030 Plan, which pledged to integrate health considerations “in all policies” and “throughout the entire process of public policymaking.” In July 2019, a Healthy China Initiative Promotion Committee was established, headed by the then-vice Premier of the State Council. Members of the committee include top-ranked officials not only from the national agencies of health, traditional Chinese medicine, tobacco, and sport but also from the labor, agriculture, rural revitalization, poverty alleviation, natural resources, ecology and environment, transportation, and housing sectors. Though the latter ministries and sectors do not focus explicitly on health, their policies can significantly impact health.

Challenges

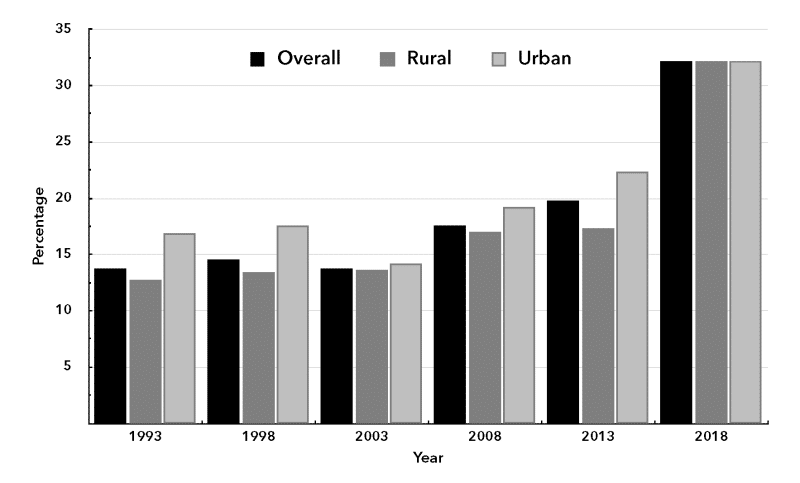

Despite China’s health care achievements during the past decade, three major challenges remain. First, some of China’s health indicators show worrying signs. Between 2013 and 2018, the average self-rated health score among individuals aged 15 years and above decreased from 80.9 to 77.3 (out of 100 possible points). The most substantial deterioration occurred in the rural sector: in 2013, the self-rated health of rural residents was 81.2, or 0.6 points higher than that of urban residents; by 2018, rural residents’ self-rated health score had declined to 75.6, or 3.3 points lower than the score of their urban counterparts. During the same period, the self-reported prevalence of ailments in the past two weeks rose from 19.8 to 32.2 percentage points, the biggest five-year increase since the 1990s (see Chart 2). Notably, this trend cannot be attributed only to aging because the increase in prevalence occurred across all age groups. It is particularly worth noting that, in relative terms, the prevalence in young age groups saw the most growth: between 2013 and 2018, the prevalence of ailments in the past two weeks among people age 15–24 years increased from 3.6 percent to 10.6 percent and the prevalence among people age 25–34 increased from 5.4 percent to 13.8 percent (see Table 1).

Chart 2. Percent of Population Self-Reporting Prevalence of Ailments in the Past Two Weeks, 1993–2018

Source: Center for Health Statistical and Information, National Health Commission, An Analysis Report of National Health Services Survey in China 2018 (Beijing: People’s Health Press, 2021), 29.

Table 1. Percent of Population Reporting Prevalence of Ailments in the Past Two Weeks by Age Group, 2013–2018

| Age Group | 2013 | 2018 | Percent Change |

| 15–24 | 3.6 | 10.6 | 194.4 |

| 25–34 | 5.4 | 13.8 | 155.6 |

| 35–44 | 11.4 | 19.9 | 74.6 |

| 45–54 | 21 | 33.1 | 57.6 |

| 55–64 | 33.6 | 46.7 | 39.0 |

| ≥65 | 46.7 | 58.4 | 25.1 |

Source: Center for Health Statistical and Information, National Health Commission, An Analysis Report of National Health Services Survey in China 2018, (Beijing: People’s Health Press, 2021), 30.

A similar trend was observed for the prevalence of chronic conditions. The most common category of chronic diseases was circulatory system diseases: between 2013 and 2018, their prevalence increased from 18 percent to 25.1 percent, and the increase was especially significant for rural residents. The percentage of people aged 15 years and above with mental illnesses doubled, as did those with nervous system disorders, both indicative of high stress levels. The rate of adults (18 years and older) being overweight or obese increased from 30.2 percent to 37.4 percent. The self-reported rate of hypertension among people ages 15 and older also increased by a quarter, from 14.2 percent to 18.1 percent. Similar to self-reported ailment prevalence, the prevalence of chronic conditions increased across all age groups, and the youngest people (aged 15–24 and 25–34) experienced the most increase in relative terms: between 2013 and 2018, the 15–24 group presented a 2.64-fold increase (from 1.4 percent to 3.7 percent) and the 25–34 group a 1.87-fold increase (from 3.8 percent to 7.1 percent).

Second, China’s government expenditure on health compared to that of countries at similar or lower economic development levels remains relatively low. In 2019, China’s government share in total health expenditure was 56.0 percent, almost identical to its 2012 level. In comparison, the share was higher in countries such as Cuba (89.3 percent), Romania (80.1 percent), Turkey (77.9 percent), Thailand (71.7 percent), Argentina (62.4 percent), Russia (61.2 percent), Kazakhstan (59.9 percent), and South Africa (58.8 percent). Also, the share of China’s government health spending in GDP was 3.0 percent in 2019, lower than that in Cuba (10.1 percent), South Africa (5.4 percent), Bolivia (4.9 percent), Namibia (4.0 percent), Brazil (3.9 percent), Russia (3.5 percent), and Peru (3.2 percent).23

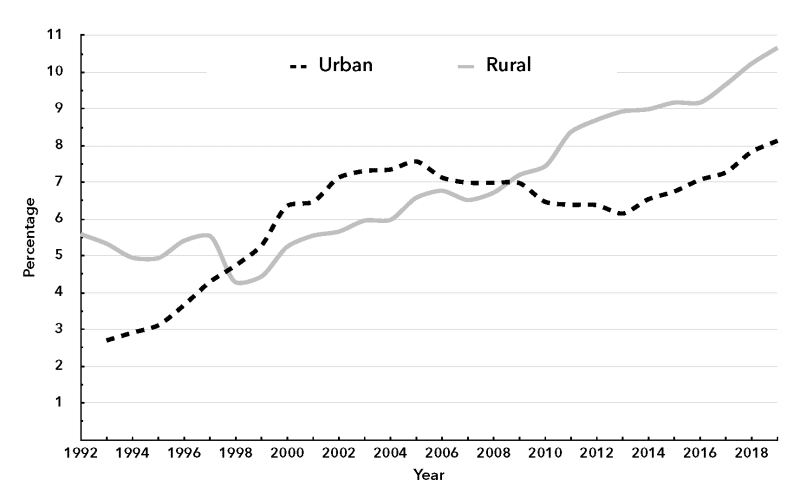

As a result of inadequate government funding, out-of-pocket spending on health remains a financial burden for many, especially the disadvantaged. Between 2012 and 2019, medical spending as a share of total household consumption increased from 6.4 percent to 8.1 percent for urban households and 8.7 percent to 10.7 percent for their rural counterparts (see Chart 3). In 2018, 33.8 percent of the surveyed respondents rated their inpatient spending “expensive,” and only 28.5 percent answered “not expensive.” Two-fifths of outpatient dissatisfaction and one-third of inpatient dissatisfaction were attributable to “expensive medical costs.” Out-of-pocket costs for an outpatient visit averaged 44.6 percent of the total expenditure; among rural residents the figure was 47.2 percent. Among formal-sector workers (comprising 23.4 percent of the population), 32.5 percent of their inpatient care costs were paid out-of-pocket; in contrast, for the majority of the population (the unemployed, informal-sector workers, and peasants), the share of out-of-pocket payment in total inpatient cost was as high as 45.4 percent. In 2018, 9.5 percent of patients had to forego hospitalized treatment because inpatient costs were high—2.1 percentage points higher than in 2013.

Chart 3. Medical Spending as a Percentage of Total Consumption, 1992–2019

Source: National Bureau of Statistics, China Statistical Yearbook (Beijing: China Statistics Press, 1995, 1996, 1998, 2020); National Bureau of Statistics, China Health Statistical Yearbook (various years) (Beijing: China Union Medical College Press, 2004, 2009, 2015).

Third, China’s patient-physician relationship is in a persistent crisis. For years, violence and even homicide against Chinese doctors has been extensively discussed in popular media and academic journals, including the Economist, the New Yorker, the Lancet, and Health Affairs.24 According to the Chinese Medical Doctor Association survey conducted in 2016 and 2017, 66 percent of interviewed doctors experienced at least one episode of verbal abuse and 15 percent had been physically injured by patients or their family members.25 A 2020 survey on the working conditions of Chinese health care workers showed that the intense doctor-patient relationship was one of the primary sources of work pressure felt by medical professionals, second only to their heavy workload.26

During the New Era, the Chinese government has developed many laws and regulations to punish violent crimes against health workers. For example, in March 2014, the Ministry of Public Security issued the Six Measures of Public Security Organs on Preserving Public Safety of Medical Institutions; in the following month, China’s Supreme Court, Supreme Procuratorate, Ministry of Public Security, Ministry of Justice, and National Health and Family Planning Commission (the Chinese equivalent to the Ministry of Health) jointly issued the Opinions of Enforcing Law on Illegal and Criminal Conducts Against Health Workers and Preserving Public Order of Medical Practice.27 In August 2015, related provisions were written into the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China.28 In December 2019, an on-duty doctor in a Beijing tertiary hospital was fatally stabbed by her patient’s son. A few days later, China’s top legislature, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, promulgated the Law on the Promotion of Basic Medical Care and Health, which contains detailed and comprehensive provisions for protecting medical workers from violence.29 Nevertheless, these legal measures have not ended, nor will they end, violence against health workers. The root causes of the violence must be addressed.

The Institutional Roots of the Challenges

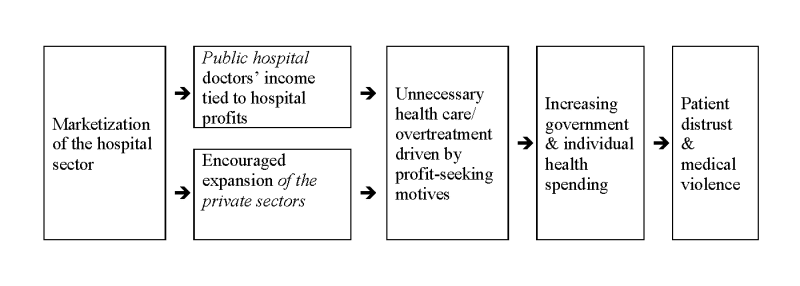

The challenges just described are interrelated, and the root lies in the marketization of health care since the late 1970s, during which public hospitals in China—owned mainly by central and local governments—were made responsible for their own profits and losses. In order to seek profits, Chinese public hospitals frequently prioritize economic gains over patient interests by performing unnecessary health care. Meanwhile, the promoted expansion of private medical institutions has further aggravated the problem. Chart 4 illustrates the mechanism of how over time, hospital marketization has increased individuals’ medical cost burdens and jeopardized trust between physicians and patients.

Chart 4. Hospital Marketization, Unnecessary Health Care, and the Patient-Physician Relationship

Source: Author’s analysis.

Marketization of Public Hospitals

The market reform of China’s public hospitals launched in the late 1970s closely followed, if not duplicated, the reform of state-owned enterprises. In April 1979, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Finance, and the National Bureau of Labour jointly issued Opinions Regarding Strengthening the Pilot Project of the Economic Management of Public Hospitals, which explicitly called for “applying economic methods to manage the operation of hospitals and maintain financial balance.”30 In 1981, the Ministry of Health, in its Report on Solutions for the Loss-Making Problem of Public Hospitals, attributed public hospitals’ financial deficits to their “excessive emphasis on the public welfare purpose.” The document proposed that to solve the problem, public hospitals should make up for losses by charging higher user fees. Public hospitals were also permitted to retain profits for employee bonuses and collective welfare expenses, which effectively tied doctors’ income to the economic performance of hospitals. The report argued that, unless the revenue of hospitals and doctors became linked to their performance, competition and incentive mechanisms would be impossible to establish and, consequently, the quality of health services would “inevitably” deteriorate.31

Since then, China’s public hospitals, which comprise most of the hospitals in China, have, like their private counterparts, largely operated under “self-funded, for-profit” principles. Their primary sources of revenue are government insurance or patient out-of-pocket payments, which are charged for the medical procedures that doctors perform and the medication that doctors prescribe. Government direct funding now plays a minor role. For instance, in 2002, government budgetary allocations only comprised about 7.5 percent of government hospitals’ total revenue. The last decade has not seen significant improvement: in 2019, about 9.7 percent of the total revenue of all China’s 11,465 public hospitals came from government allocations, accounting for 28.3 percent of their personnel expenditure.32 In other words, on average, nearly 90 percent of a public hospital’s revenue, or more than 70 percent of its wage bill, depends on selling checkups, procedures, drugs, and medical consumables.

Kenneth Arrow, a Nobel Prize laureate in economics, once famously said, “the very word, ‘profit,’ is a signal that denies the trust relations.”33 Once hospitals and doctors are allowed, expected, and even encouraged to make profits, Pandora’s box opens wide. Because health care providers have an asymmetric information advantage in medical knowledge, they can exploit both public insurance and the patients simply by prescribing more (and more expensive) drugs and services. Consequently, unnecessary medical care has increasingly become standard practice across the country, driving up health care costs and ruining the patient-physician relationship. Thus, a vicious spiral of high medical spending, on the one hand, and mistrust between patients and physicians, on the other hand, becomes established. That is, increased medical costs undermine patients’ trust and satisfaction in doctors; to reduce their exposure to malpractice claims or even physical attacks, doctors respond with defensive medicine that further escalates health care spending. This explains why, despite growing government health spending, patients’ out-of-pocket expenditures—both absolute and relative to total consumption—have kept scaling up.

A particularly illustrative example of unnecessary care and its consequence is China’s unreasonably high prevalence of births via Cesarean section. While the WHO suggests a country’s “ideal” rate of Cesarean sections should be close to 10–15 percent, China’s 2018 national Cesarean section rate reached 36.7 percent.34 Such a high rate is mostly attributable to economic rather than clinical factors. Because Cesarean section operations are twice as expensive as vaginal births and appear more technically sophisticated, by recommending non-medically indicated (elective) Cesarean sections to women, doctors can “make more profit from the higher insurance reimbursement and receive ‘tips’ from families.”35 Moreover, to avoid malpractice lawsuits relating to vaginal delivery, many doctors prioritize Cesarean section to avoid litigation. A 2017 survey shows that 8.2 percent of 1,500 surveyed Chinese physicians practicing obstetrics and gynecology “strongly agreed” or “agreed” with performing Cesarean sections without indications. Another 33.9 percent of physicians indicated “no opposition” to such unethical practices.36

Persistent Expansion of the Private Hospital Sector

The problems of unnecessary medicine use and escalating health spending have been further exacerbated by the continued expansion of the private hospital sector. Between 2012 and 2020, the number of hospitals in China increased from 23,170 to 35,394, among which the share of private hospitals increased from 42.2 percent to 66.5 percent. For medium- and large-scale hospitals (more than 200 beds), the private share experienced a striking expansion—from 7.3 percent to 24.6 percent. In terms of hospital beds, between 2012 and 2020, the number of private hospital beds more than tripled, from 580,000 to 2.04 million, and their share doubled from 14 percent to 28.6 percent.

The sustained growth of private hospitals has been actively encouraged and facilitated by the government. The belief that market competition optimizes efficiency and benefits customers has been profoundly embedded in policies and regulations. For example, an official document issued in 2010 stated that encouraging and guiding the engagement of private medical institutions would create a “competition mechanism” that could help improve the quality and efficiency of health services.37 It was also stipulated that local governments and departments should “emancipate the mind and transform old ideas” to remove the barriers keeping the private sector from developing. Further, in the Twelfth Five-Year Plan for the Development of Medical and Health Services, issued in 2012, a concrete goal was set: by 2015, the market share of private-sector hospitals, measured in terms of the numbers of hospital beds and patients, should have reached 20 percent.38 Some municipal governments set an even more ambitious target of 30 percent.39

To achieve these quantified targets, governments at different levels offered to private hospitals a level of preferential treatment that was rarely found elsewhere. For example, in 2013, the central government extended preferential rates on infrastructure utilities (electricity, water, gas, and heat) that were previously offered only to public hospitals to all private health institutions, including for-profit hospitals.40 In some places, the local government pledged to reimburse private tertiary hospitals as much as 40 percent of their annual corporate taxes. Also, some local governments promised to reward private hospitals that have newly achieved the highest hospital accreditation level with lump sums of 20 million RMB (the equivalent of $3 million). In other cases, private, nonprofit medical institutions were permitted to reward shareholders with 40 percent of their net profits. Some local governments banned the expansion and new construction of public hospitals in urban center areas, but gave the green light to their private counterparts.

Inadequate Emphasis on Social Determinants of Health

Last but not least, the so-called “big health” spirit has not yet been effectively translated into concrete measures, which at least partly explains why, despite increased insurance coverage and government health spending, some critical overall health indicators (such as self-reported health scores and the reported prevalence of illness within two weeks) have recently deteriorated, and chronic diseases have increased the most among younger people. In the aforementioned Law on Basic Health Care and Health Promotion, which came into force on June 1, 2020, only one chapter (among ten) addresses non-medical health determinants. Moreover, it addresses the issue through a traditional public health approach: its central theme is the role that government plays in influencing individual health behaviors through health education programs. For instance, Article 67 stipulates that governments at all levels shall establish an information distribution system of scientific and accurate health knowledge and skills; Article 68 stipulates that schools shall popularize fitness and first-aid expertise and help students to cultivate healthy hygiene habits and lifestyles. The law also emphasizes personal responsibility by stating that individuals shall “undertake the primary responsibility for their own health” through practicing “self-management of health and disease.”

Working conditions, an essential component of the social determinants of health, are mentioned only in Article 79. They are mentioned only in passing, and the law fails to identify the mechanism through which work influences health. After laying out the guiding principle that “employers shall create environment and conditions favorable to employees’ health,” the law touches only on technical matters, such as “organizing employees to carry out fitness activities” and “carrying out regular health examinations for employees when possible”; the wording appears discretionary and advisory. Nothing is said about critical health determinants such as job precarity, work hours, occupational health hazards, or health risks that stem from domination, control, and exploitation in the workplace hierarchy.

Concluding Remarks

During a talk to medical professionals in 1965, Chairman Mao criticized China’s health system: “A medical team is considered good by the hospital if it makes profits; otherwise, it will be regarded as not good. Are they people’s hospitals?”41 This remark still resonates strongly today. In the report Xi presented to the Twentieth National Congress of the CPC in October 2022, the Party announced that China will become “a leading country” in health by 2035 and pledged to “deepen reform of public hospitals to see that they truly serve the public interest.”42 This will require structural reforms. For one thing, the government must sever the economic connection between the income of hospitals and doctors and how many medical procedures and tests they perform or how many medications they prescribe. The pay scale of doctors who work in public hospitals must be primarily linked to their fulfillment of medical responsibilities rather than their profitability; incentives should be structured to elicit a high quality of care, rather than high volume. Otherwise, increasing government health spending alone may have an unintended effect: the injections of public funds into the deep pockets of renowned hospitals, elite physicians, and monopolistic pharmaceutical and medical companies.

Health care is only one component of overall health and well-being, and it is not the most critical determinant of health. Despite nearly universal health insurance and improved access to health resources, the deterioration in some of China’s major population health indicators—particularly the multiplication of chronic diseases among younger cohorts—deserves focused attention. Medicine does not resolve chronic problems, and health programs that focus on behavioral and lifestyle modifications are also insufficient. Health should not be treated as a technological matter; it is, by nature, an economic, social, and ultimately political matter determined by the distribution of power and resources. As a socialist-oriented country with a relatively large state sector and strong state capacity for macroeconomic planning and regulation, China should take full advantage of its potential to mobilize resources and power to build a health-enhancing society.

Indeed, China’s public health has already benefited tremendously from its unique institutional infrastructure. A 2019 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that China successfully reduced excess deaths attributable to particulate matter by 370,000, or 92 percent of the total avoided deaths in 2017.43 Since 2013, this success has been achieved by implementing a series of stringent measures, including strengthening industrial emission standards, upgrading industrial boilers, phasing out outdated industrial capacities, and promoting clean fuels in the residential sector. These measures, developed out of China’s radical conception of an ecological civilization, are less likely to be formulated and implemented in Western countries because they frequently go against the economic interests of corporations.

The connection between ecological measures and the resultant health benefits should serve as an illustrative example for how to develop national health laws, policies, and strategies. To safeguard the health of populations and individuals, policymakers should account for a wide range of health determinants such as working conditions, housing, income inequality, gender, fiscal austerity, and deregulation. For example, as the nation battles economic headwinds, China’s youth unemployment rate in urban areas has reached a record high (16.7 percent as of December 2022); meanwhile, the rise of the gig economy increasingly traps workers in a precarious existence.44 Given that both unemployment and job precarity pose grave threats to health, the government should actively intervene by enforcing the rules of labor and generating more, and more stable, public-sector jobs.45 These actions not only stabilize the labor market and, hence, sustain social and political order, they also prevent “social murder” (in Fredrick Engels’s words) and deliver health in a fundamental fashion.46

Notes

- ↩ According to the 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer, trust among Chinese citizens in their government is a record 91 percent, continuing to top the list. In contrast, only 39 percent of respondents in the United States said that they trusted their nation’s government. For details, see “Edelman Trust Barometer 2022,” available at edelman.com.

- ↩ Mao Zedong, “Postscript to Two Poems of Farewell to the God of Plague,” in Collections of Mao Zedong’s Poems (Beijing: CPC Central Documents Research Office, 1996), 234–35.

- ↩ Government Administration Council, “Labour Insurance Regulations of China,” People’s Daily, February 27, 1951, 1.

- ↩ National Statistical Bureau, A Compilation of Historical Statistical Data of Provinces, Autonomous Regions, and Municipalities 1949–1989 (Beijing: China Statistics Press, 1990); Mao Zedong, “Some Interjections at a Briefing of the State Planning Commission Leading Group on the Third Five-Year Plan, May 10–11, 1964 (Excerpt),” in Selected Important Documents Since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China, vol. 18 (Beijing: CPC Central Documents Research Office, 1996), 495–97 [in Chinese].

- ↩ Mao Zedong, “Directive on Public Health,” in Chronological Biography of Mao Zedong, vol. 5 (Beijing: Central Documents Press, 2013), 506.

- ↩ World Bank, World Development Indicators, databank.worldbank.org.

- ↩ The author’s calculation based on data from China Social Statistics 1990 (Beijing: China Statistics Press, 1990), 212.

- ↩ Cui, “China’s Village Doctors Take Great Strides,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 86, no. 12 (2008): 914–15.

- ↩ Ministry of Health, Report to the State Council on Properly Solving the Subsidy Issue for Barefoot Doctors, February 16, 1981.

- ↩ World Bank, World Development Indicators.

- ↩ Ding and Q. Zhou, “The God of Plague Has Come Back,” Outlook Weekly, February 7, 2004.

- ↩ Center for Health Statistics and Information, National Health Commission, An Analysis Report of National Health Services Survey in China 2018 (Beijing: People’s Health Press, 2021), 25.

- ↩ World Health Organization, World Health Report 2000, who.int.

- ↩ Wang, “A Latest Report of the State Council Research Center Says, China’s Healthcare Reform is Unsuccessful,” China Youth Daily, July 29, 2005.

- ↩ Wang, “Director of the State Agency Handling Complaints and Petitions: Investigation Shows that 80 Percent of the Petitions Were Well-Grounded,” Southern Weekly, November 20, 2003.

- ↩ Wang, A. Hu, and Y. Ding, “Social Instability behind Economic Prosperity,” Strategy and Management, no. 3 (2003): 6–33 [in Chinese].

- ↩ Zhang and X. Chen, “Does ‘Class Count’? The Evolution of Health Inequalities by Social Class in Early 21st Century China (2002–2013),” Critical Public Health 33, no. 1 (2023): 13–24.

- ↩ Li Rongde, “Xi Jinping Lauds ‘New Era’ for Socialism in Modernizing China,” Caixin Global, October 18, 2017.

- ↩ “Xi Jinping Delivers Speech at the Symposium of Ministers and Provincial Leaders on Studying the Spirit of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s Important Speeches for the Party’s Upcoming 19th Congress,” Xinhua, July 27, 2017 [in Chinese].

- ↩ Statistics for life expectancy are from the Bulletin of National Health Development Statistics 2021, July 12, 2022, nhc.gov.cn; statistics for infant mortality are from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators.

- ↩ Tan, X. Liu, and H. Shao, “Healthy China 2030: A Vision for Health Care,” Value in Health: Regional Issues 12 (May 2017): 112–14.

- ↩ Horton, “Offline: China’s Rejuvenation in Health,” Lancet 389, no. 10074 (2017): 1086.

- ↩ World Bank, World Development Indicators.

- ↩ “Violence Against Doctors in China is Commonplace,” Economist, April 24, 2021; A. Tussing, H. Wang, and Y. Wang, “Chinese Doctors in Crisis: Discontented and in Danger,” Health Affairs (blog), May 27, 2014; Editorial board, “Protecting Chinese Doctors,” Lancet 395, no. 10218 (2020); C. Beam, “Under the Knife: Why Chinese Patients are Turning Against Their Doctors,” New Yorker, August 25, 2014.

- ↩ Chinese Medical Doctor Association, White Paper on the Working Conditions of the Chinese Doctors, December 2017, medtrib.cn.

- ↩ Yixuejie Think Tank, “The 2020 Working Conditions of Chinese Medical and Care Workers,” September 19, 2020, sohu.com.

- ↩ “Opinions of Enforcing Law on Illegal and Criminal Conducts Against Health Workers and Preserving Public Order of Medical Practice,” Procuratorate Daily, April 28, 2014, spp.gov.cn.

- ↩ Ninth Amendment to the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China, August 30, 2015, npc.gov.cn.

- ↩ Law of the People’s Republic of China on Basic Medical and Health Care and the Promotion of Health, December 28, 2019, gov.cn.

- ↩ Ministry of Health, Ministry of Finance, and National Labor Bureau, Opinions Regarding Strengthening the Trial Work of Public Hospitals’ Economic Management, issued April 28, 1979, fgcx.bjcourt.gov.cn.

- ↩ Ministry of Health, Report on Solutions for the Loss-Making Problem of Public Hospitals, February 27, 1981, gov.cn.

- ↩ Author’s calculation based on National Health Commission, China Health Statistical Yearbook (2003, 2020).

- ↩ Arrow, “Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical Care,” American Economic Review 53, no. 5 (1963): 941–73.

- ↩ World Health Organization, “WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates,” April 14, 2015, who.int/publications; Hong-tian Li et al., “Trends in Cesarean Delivery Rates in China, 2008–2018,” Journal of the American Medical Association 323, no. 1 (2020): 89–91.

- ↩ Mi and F. Liu, “Rate of Caesarean Section is Alarming in China,” Lancet 383, no. 9927 (2014): 1463–64; Lili Kang et al., “Rural-Urban Disparities in Caesarean Section Rates in Minority Areas in China: Evidence from Electronic Health Records,” Journal of International Medical Research 48, no. 2 (2020): 1–13.

- ↩ Zhu, L. Li, and J. Lang, “The Attitudes Towards Defensive Medicine Among Physicians of Obstetrics and Gynecology in China: A Questionnaire Survey in a National Congress,” British Medical Journal Open 8, no. 2 (2018): e019752.

- ↩ Ministry of Health et al., Guiding Opinions Regarding the Trial Reform of Public Hospitals, issued February 11, 2010, nhc.gov.cn.

- ↩ State Council, Twelfth Five-Year Plan for the Development of Medical and Health Services, October 8, 2012, gov.cn.

- ↩ In 2015, the author participated in a World Bank program, investigating the development of private medical institutions in southern China. Participants of the program visited a number of hospitals (both private and public) and interviewed local government officials and hospital managers.

- ↩ State Council, Several Opinions on Promoting the Development of Health Services Industry, issued October 18, 2013, gov.cn.

- ↩ Liu, “Mao Zedong and the Medical and Health Work in the New China,” Extensive Survey of the CPC’s History, no. 5 (2016), 4–9 [in Chinese].

- ↩ Xinhua, Report to the Twentieth National Congress of the CPC, October 25, 2022, english.www.gov.cn.

- ↩ Qiang Zhang, Yixuan Zheng, Dan Tong, and Jiming Hao, “Drivers of Improved PM2.5 Air Quality in China from 2013 to 2017,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, no. 49 (2019): 24463–69.

- ↩ Wang, “Employment Continues to be a Policy Priority, and the Labor Market Remains Stable in General,” January 18, 2023, www.ce.cn.

- ↩ Carles Muntaner et al., “Unemployment, Informal Work, Precarious Employment, Child Labor, Slavery, and Health Inequalities: Pathways and Mechanisms,” International Journal of Health Services 40, no. 2 (2010): 281–95.

- ↩ Stella Medvedyuk, Piara Govender, and Dennis Raphael, “The Reemergence of Engels’ Concept of Social Murder in Response to Growing Social and Health Inequalities,” Social Science and Medicine 289 (2021): 114377.

Comments are closed.