Also in this issue

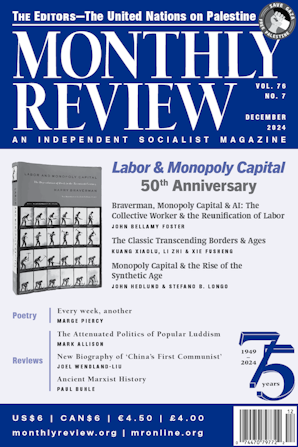

- December 2024 (Volume 76, Number 7)

- Braverman, Monopoly Capital, and AI: The Collective Worker and the Reunification of Labor

- The Classic Transcending Borders and Ages: Commemorating the Fiftieth Anniversary of ‘Labor and Monopoly Capital’

- Monopoly Capital and the Rise of the Synthetic Age

- Every week, another

- Preface to the German Edition of Marx’s Ecology

- The Attenuated Politics of Popular Luddism

- New Biography of “China’s First Communist” Reveals Nuances for English-Speaking Readers

Books by Paul Buhle

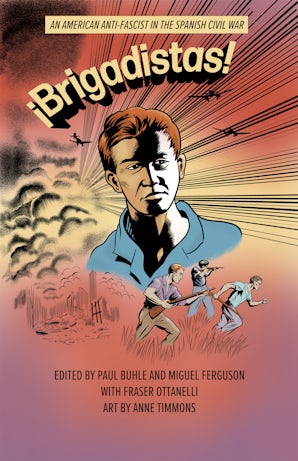

¡Brigadistas!

by Miguel Ferguson and Fraser M. Ottanelli

Illustrated by Anne Timmons

Foreword by Paul Buhle

Taking Care of Business

by Paul Buhle

Insurgent Images

by Mike Alewitz and Paul Buhle

Foreword by Martin Sheen

Article by Paul Buhle

- Repression in the Classroom

- Insectopolis and the Fantastic Peter Kuper

- Hubert Harrison: A Giant Remembered

- The Long Road of Tariq Ali

- Empire and Popular Arts: A Note on Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz's "Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States"

- Palestine, Oh, Palestine!

- The Left and the Class Struggle

- Two Intellectual Giants of the American Left

- The Struggle for Scotland's Future