And I say: the oppressed never ask who the oppressed are because they know. State ministers, mine or factory owners never say they are oppressed. Do you think they are part of the concept of the oppressed that I use in Pedagogy of the Oppressed? Who belongs to the concept of the oppressed that I use? They are the oppressed classes.

This article analyzes land struggles as a constituent element of Latin American and Caribbean popular history, with a particular focus on Brazil. It examines Indigenous, peasant, and Quilombola (maroon) resistance, and attempts to address a central question: What lessons do these groups’ histories of resistance offer us for current struggles, and how do they inform the construction of popular power in the twenty-first century?1

Our fundamental premise is that Indigenous, peasant, and Quilombola resistance is a defining element of the class struggle in Brazil. Recovering this history in its full complexity remains challenging, due to how colonial violence has shaped Brazil’s official history—both in the colonial past and the forging of the nation-state—which has rendered these experiences invisible or reduced them to criminalized stereotypes. Yet, while this history has been suppressed, it has not been completely eliminated. We can try to recover it by examining popular culture and by engaging in popular education, which involves ongoing learning processes alongside communities to reveal how they have lived over time and survived the onslaught of capital.

As we recover experiences of resistance, looking at material processes in the daily life of Indigenous, Quilombola, and peasant communities over time, we encounter a mosaic full of conflicts and contradictions. There are also significant lacunae, because the invaders of yesterday and today have buried so many of the accounts of the resistance to oppression and exploitation that has occurred over the past five centuries.2

Indigenous, African, and peasant Brazil has survived and continues to exist today, despite the processes and projects of criminalization and genocide that have been carried out against their lives and communities for five hundred years. The struggles of these groups for land and the maintenance of their communities help us understand a history of Brazil that is not to be found in official history books. A samba-enredo (theme song) from 2019 captures our conception of this alternative history when it refers to “The story that history does not tell, the flip side of the same place.”3

A large part of the popular social bloc in Brazil comprises Indigenous and Afro-descended peoples as well as peasants. As a result of dependent capitalism, they have tended to become dispossessed, landless, superexploited, and unfree.4 Dependent capitalism, despite the existence of formal freedoms, established a new kind of de facto slavery from the nineteenth century onward. That is because dependent economies typically intensified internal economic and social inequalities to be able to transfer value to the metropoles. In Brazil, the state took the lead in bringing this about through its oppressive development policies. The result was that Indigenous and Afro-descended peoples, as well as peasants, were made into the eternal wretched of the earth.

This article highlights how one can learn from and draw hope from these stories of resistance. It also reveals the injustice of a system that produces mercantile wealth and legal protection for the few while relegating the vast majority to penury and denying them social, political, economic, and cultural rights. The article is inspired by the tradition of Latin American and Caribbean Marxist theory that draws on historical and social struggles, and emphasizes the need to situate oneself on the side of the popular social bloc. The latter is a class bloc that is actively constituted as inferior, not only by capital but even by part of the left when it comes to the task of building popular power.

Discovery or Invasion? Genocide, Ethnocide, and Memoricide

On April 22, 1500, a group of sailors heading for the East Indies arrived to a hitherto unknown territory in the southern part of what is now known as Latin America. They claimed to have “discovered” it. For these self-proclaimed explorers, the sight of land—memorialized through their cry of “Terra a vista“—led to an encounter with new subjects, forms of sociability, conceptions of life and death, and forms of development. Social bonds in the south of the continent were typically produced through collective and communal practices. These included gathering, hunting, and fishing, along with the great variety of agricultural methods that were employed in the great forests (the Atlantic, Amazon, Pantanal forests, among others).

These invading “discoverers” were profoundly ignorant about the territory and the peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean. They called every colonized subject an “Indian” and identified them as lesser beings, applying a belligerent logic that contributed to fundamental inequalities. In that way, “Indian” became a standard classifying, and homogenizing term that spoke to their aim of colonizing, enslaving, and appropriating an entire complex process of producing life and culture in the region. Yanomamis, Guaranis, Tupis, Tupinambás, Tupiniquins, Botocudos, Xavantes, Aymara, and other peoples were all considered Indians. The invasion led to the original modes of production mostly succumbing, not without resistance, to the logic of colonial enslavement and domination.5

The Portuguese claim on the region meant that the colonial enterprise had to be synonymous with war. It was a war both because of their commercial disputes with the other colonizing and enslaving European countries and because they forced their processes of development onto that hitherto autonomous territory. The period of 1500–2000 in South American history saw a reordering of social relations, ways of producing life, and artistic and cultural processes. Everything that existed was branded as barbaric, according to the civilizational criteria coming from a Europe that was experiencing a continual power crisis.

Europe would not have moved as it did from feudalism to capitalism between the 1500s and 1700s without this invasion, called a “discovery,” that destroyed peoples and their ways of life. The “so-called primitive accumulation” that Marx wrote about allowed for the rise of industrial capital, and later, financial capital. Their rise depended on the genocide, looting, and the expropriation-exploitation that was carried out through colonialization and slavery.

The catastrophic invasion plunged the continent’s peoples into servitude. Reconstructing the pre-invasion history of Latin America and the Caribbean is extremely difficult. It requires repeatedly beginning again with a view to discovering what still remains unknown. That is to say, we must continuously reread history based on new findings, given the terrible destruction of the continent’s original modes of production, the enslavement of its peoples, and the violent logic of genocide, ethnocide, and memoricide that was applied here.6 In Brazil, the past of its original peoples was systematically buried, stolen, and erased, making today’s efforts to rebuild an authentic and plural historical narrative extremely challenging.

With every new archaeological and ethnological finding, the information we have undergoes a sea change. The closer we get to this destroyed history, the more we are surprised by the new discoveries that emerge from all across the continent. The invasion tried to erase the history of the original peoples of Brazil by making the first year of colonialization into the alleged starting point of our history. It was a concrete exercise in violence presented as salvation, both by Christianity and by the Europeans. The scale of the destruction is staggering: the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) estimates that one to six million Indigenous people lived in the territory at the time of the colonial invasion, yet by the twenty-first century they numbered less than three hundred thousand.7

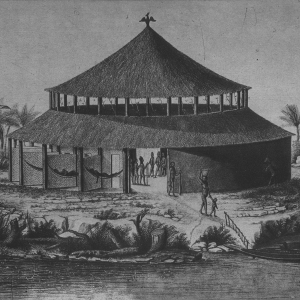

Looking at the reception of images and stories can help us trace how Indigenous modes of life were negated and demonized. In the eighteenth century, the portrait painter Alexandre Rodrigues Ferreira made drawings that showed the diversity of production methods in Brazil during this period, when Indigenous peoples were struggling for survival in the face of colonial slavery.8 For example, his representation of a Curutú household in the northern region of Brazil (see Image 1) revealed a sociability that balanced work and free time. The image also showed how they employed natural elements and architectural knowledge to construct their houses, the nature of their collective dwellings, and the harmonious relationships between people of different ages and genders.

Overall, Rodrigues Ferriera’s original drawing of the Curutú household depicted both productive social relations and Indigenous technical development. However, the same image would later be reproduced and consumed in a stereotypical fashion, when seen through the lenses of the West’s violent developmental logic and its official historiography. Such imagery was taken to show how the original peoples of the Americas were barbarians, savages, uncivilized, backward, and violent—in other words, they were peoples “without culture.” This kind of manufactured narrative demonstrates why we must read history against the grain.

Image 1. Curutú Household, Late 18th Century

Sources and Notes: Illustration of a collective dwelling in a Curutú village, northeastern Brazil. The drawing reveals the communal and cooperative lifeways of the Indigenous Curutú people and the balance of production and social reproduction in daily life. Original print from Alexandre Rodrigues Ferreira, Viagem Filosófica pelas capitanias do Grão Pará, Rio Negro, Mato Grosso e Cuiabá, 1783–1792 (Rio de Janeiro: Conselho Federal de Cultura, 1971), 126.

William Shakespeare’s The Tempest exemplifies the imagery produced by the metropoles’ official chroniclers. The drama represents Indigenous Americans as barbaric people-eaters, literally embodied in the figure of Caliban (a play on cannibal). Meanwhile, Prospero, the displaced European nobleman, is associated with the kind spirit Ariel and aims to bring development to “backward” peoples.9 Thus, the story mythologizes the “discovery” as bringing civilization, all of it connected to the theme of salvation. This fiction is no accident: the Catholic Church, mercantile capital, and European landlords collaborated for centuries to produce images and ideas that dressed up their plundering, decimation, and exploitation of peoples as palatable fictions.

Violence against the Peoples of the Americas and Africa: Slavery as a Common Denominator

Across the British, French, Dutch, and Spanish colonies, the turn to enslaved African labor emerged from three converging pressures: the catastrophic demographic collapse of Indigenous populations, the metropoles’ growing demand for resource extraction over the colonial period, and sustained Indigenous resistance to colonial exploitation and oppression.

Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, almost twelve million Africans were enslaved and transported to the Americas, with Portugal forcibly bringing five million to Brazil alone.10 The epicenter of slavery initially was Brazil’s Northeast before spreading southeastward and into the country’s interior. Over time, Indigenous and African slavery changed in keeping with the economic cycles of colonial development. The violent practice of enslaving human beings for the sake of accumulation shaped the whole continent’s history and the specific colonial history of Brazil. As political scientist and historian Luís Felipe de Alencastro points out:

During these three centuries, millions of Africans came to this side of the Atlantic who, amid misery and suffering, had the courage and hope to form the families and cultures that make up an essential part of the Brazilian people. Torn forever from their families, their villages, and their continent, they were deported by Luso-Brazilian slavers and then by genuine Brazilian traffickers who brought them back chained in ships flying the green-gold banner of our land….11

The formation of the Brazilian nation—and later, its precarious nineteenth-century republic—was inextricably tied to the enslavement of Indigenous and African peoples. Despite their marginalization, these two social groups created their own economic, social, political, religious, cultural, and artistic systems through processes of resistance and struggle that remain largely erased from national memory. Their struggles against bondage during the nearly four centuries of colonial slavery have been excluded from official histories. That is why we must turn to oral history, popular memory, and archaeological discoveries to construct an alternative to official history.

Brazil’s entire mode of production rested on a foundational contradiction: an economic system built by enslaved Indigenous and African populations who were systematically excluded from citizenship. These were the “nobodies” referred to in Eduardo Galeano’s famous poem—the dispossessed masses who still haunt the streets in Latin America’s dependent capitalist cities.12

The history of mixed racial identity also emerges, a violent saga of structural racism and enduring stereotypes. In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the treatment of racially mixed people and their descendants reflects the deep-rooted legacy of slavery—no longer in the horrors of slave ships and plantations, but in everyday politics, superexploitation, and derogatory cultural imagery.

Guillermo Bonfil Batalla’s 1987 book México Profundo contended that there was a “Deep Mexico” with pre-Columbian roots that could be contrasted with the “Imaginary Mexico” based on colonial structures that erased history and a restricted conception of civilization.13 The same idea can be applied to Brazil, where there is a Deep Brazil, with its own histories and its own Indigenous and African modes of production. The underrecognized Deep Brazil has a plural, diverse structure and operates with a notion of wealth that is fundamentally different from capitalist accumulation.

By contrast, Imaginary Brazil has a legal and political configuration that keeps a significant part of the people who built our history relegated to the condition of commodities—that is, non-subjects. The dialectical relation between these two worlds resonates with the viewpoint of Clóvis Moura, an important Brazilian sociologist who studied racial oppression in Brazil. Moura pointed out how full slavery (“escravismo pleno“) had transformed into late slavery (“escravismo tardio“), in which a significant group of citizens is relegated to the status of non-subjects by the rule of law itself.14

In the current century, Black authors of all genders have gained more prominence in academic debates, thanks to the just demands made by Black and feminist social movements. In the twentieth century, those who investigated the question of racial oppression and resistance sometimes became well-recognized figures, but they had low academic profiles. Even in left political parties, only a few male figures who studied Brazil’s social formation were given prominence, while other investigators were kept in the shadows. Fortunately, the struggles of the continent’s social movements have not only changed this situation, but have led to both new sources of information and renewed research into subjects, territories, and territorialities.

One important research focus for those aiming to recover the political subjects involved in resistance, uprisings, and revolutions is the Quilombo of Palmares, founded in 1580 in the Northeastern state of Pernambuco. There is also research into the social movements fighting for land and into the diverse forms of Indigenous resistance that occurred throughout Brazil. Much new information will surely come forth in upcoming centuries, based on oral history and looking at the gaps in the historical record.

However, even by re-reading existing accounts, such as those of Bernardo de Sahágun, Bartolomé de las Casas, and José de Anchieta—along with looted sources in Europe and the United States—we can uncover stories that challenge official history. In these sources (including reports, drawings, and song collections), one finds information that, although it does not accurately measure the scale of the uprisings, still reveals a continent marked by constant rebellion.

Brazil had almost four hundred years of formal slavery and has an even longer history of highly concentrated land tenure (latifundia). Throughout this history, narratives of resistance emerge—not just tales of displacement and exploitation, but also stories of those who fought for autonomy, subsistence, and ways of living beyond capital’s relentless cycle of impoverishment. Even in a context marked by racism, eugenics, and state-sponsored “whitening” policies, these struggles persisted, challenging the very foundations of the capitalist order.15

During the period of formal slavery, the flight of enslaved people was a struggle for freedom, and it was always connected to the collective organization of the land. It was not only a question of fleeing bondage, but of survival and creating new forms of community and non-mercantile modes of production. The struggle to survive and produce in this way generated projects of resistance all over the continent that, in their opposition to colonial and neocolonial private owners, constitute a history of life beyond capital. It involved self-management, territorial self-defense, and productive and political organization guided by principles and values that were anchored in life-sustaining agriculture.

The struggle for land in Brazil has always been, at its core, a fight for alternative ways of living. From resistance to colonialism to defiance of the capitalist mode of production, these struggles have sought not just the freedom from the wage regime, but substantive liberation rooted in autonomy, collective survival, and defiance of exploitation. Today’s landless peasants and rural poor inherit this legacy of Indigenous and Afro-Brazilian resistance. Their ongoing fight to sustain communal production and resist the ruthless expansion of agribusiness in the service of capitalist accumulation continues a centuries-long battle.

Despite the transition from the mercantile-slave mode of production to industrial-financial capitalism, there are enduring continuities in popular struggle. Today’s landless peasants and proletarianized workers inherit this legacy, forming the contemporary social bloc of resistance. The quilombos exemplify this centuries-long fight for self-determination across Latin America and the Caribbean, which was also embodied in the revolutionary Haitian uprising of the eighteenth century. That watershed moment, led by Black revolutionaries, not only achieved national independence but also inspired popular movements across the continent.16

Resistance to Capitalism’s Violent Offensive and its Nation States

The history of the Palmares Quilombo in the seventeenth century resonates with the struggles of our time. The 2016 samba-enredo “Palmares, Um Modelo de República Popular” (“Palmares, a Model of a People’s Republic), by the São Paulo samba group Pega o Lenço vai-Mauá, captures this idea:

We’ve come to pay tribute to

An important milestone in the history of Brazil

Palmares was the womb of our freedom

I tell the truth, and I don’t overlook it

For more than sixty years, it resisted

Its quilombos came to show

A model of a popular republic

On the soil of Pernambuco

The great revolution took place

Its warriors wrote the pages of abolition

Palmares land of freedom

Lives in our hearts.17

Even today, there are 8,441 recognized quilombo territories in Brazil with a self-identified Quilombola population of 1.3 million people. The agrarian question remains central to their struggle, since a mere 4.33 percent of this population lives in officially regularized territories, while the overwhelming majority (85.62 percent) remain in legal limbo, their struggle for land rendered invisible by the state. They are in great measure subjects without rights from the perspective of the Brazilian state.18

The fight for land—foundational to every mode of production—has shaped Brazil’s popular struggles across successive economic cycles. But how can we reclaim a history that has been systematically erased, distorted, and dismissed as marginal? How do we challenge dominant academic narratives that overlook five centuries of resistance by Indigenous peoples, Afro-Latinx communities, and peasants, groups who have resisted dispossession and capitalist accumulation?

The story of the Palmares Quilombo stands out as one of Brazil’s most important narratives of Black resistance, not just for its impressive longevity, but for withstanding repeated assaults on its economic, social, and political foundations. The aim was not just to defeat Palmares militarily but to eliminate it as a symbol. The colonial powers understood that if the quilombo were victorious, this process of confrontation, resistance, and successful struggle would have spread throughout the country.

Moura conceptualizes quilombos as spaces of life-production operating beyond the spatiotemporal logic of colonial slavery.19 He frames quilombagem (maroonage) as a centuries-old political practice of Afro-Latinx resistance—a struggle against the erasure of Black history and culture, rooted in the fundamental right to self-determination. For Moura, the quilombo represented the basic unit of enslaved people’s resistance.20 In addition to that kind of resistance, other forms of struggle appeared including direct warfare, collective suicide, and military organization.

The Quilombo of Palmares represents to Brazil what the Black Jacobins’ struggle was to Haiti: autonomous Black states that redefined freedom itself through their struggle for land and self-determination. Both movements embodied a radical alternative to the hollow “freedom” offered by republicanism, which merely transformed enslaved Africans into superexploited proletarians within global capitalism. As historian Edison Nascimento emphasizes: “The Quilombo was a perpetual call—a rallying cry, a banner of hope for enslaved Black people in the surrounding areas. It stood as an enduring summons to rebellion: to flee into the wilderness, to fight for freedom.”21

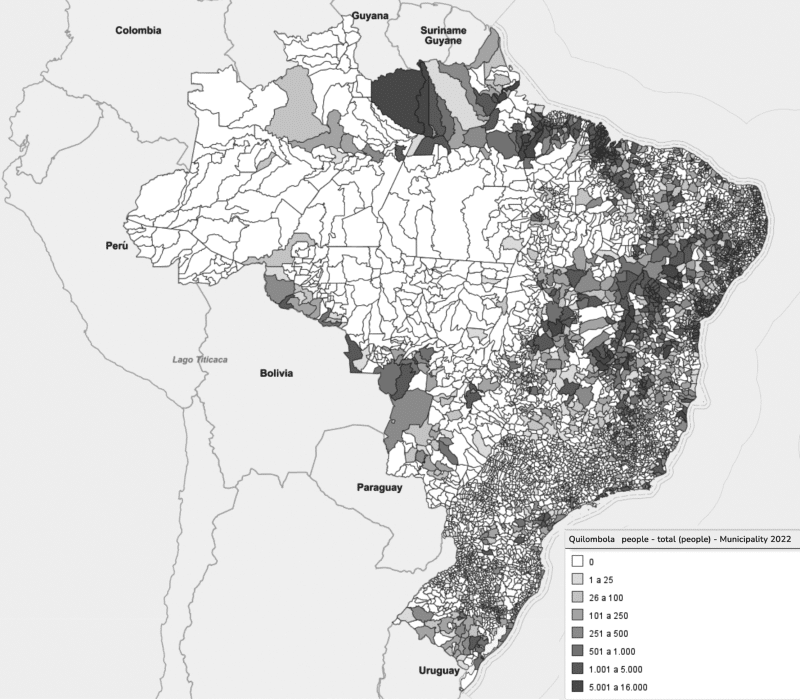

Brazil’s 2024 IBGE census was the first to collect data on self-identified Quilombola subjects. This data offers useful clues for reconstructing the history and memory of these communities by examining the daily lives of those inhabiting Quilombola territories. Such communities have maintained their own distinct economic, social, cultural, and political processes despite the retreat of the continent’s social struggles.

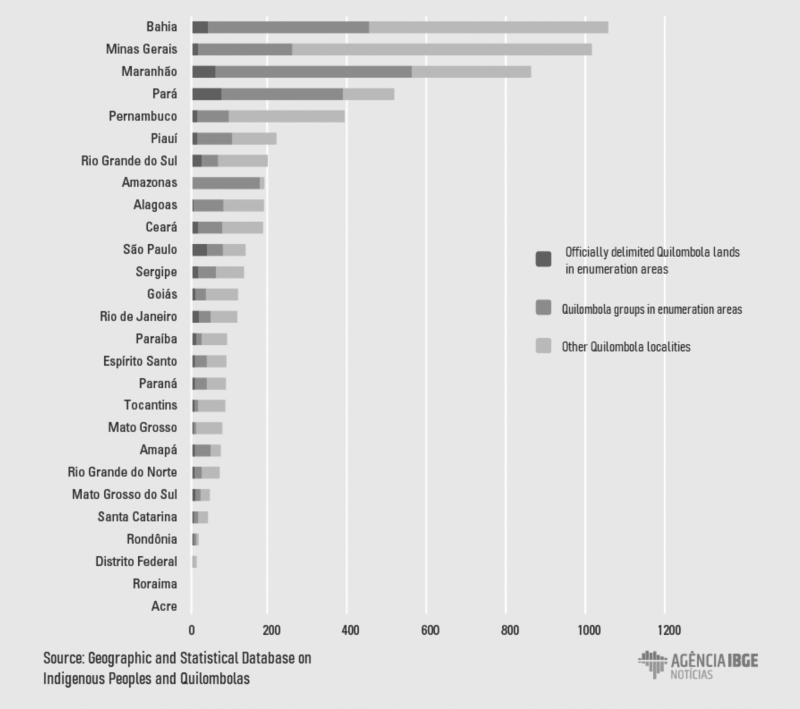

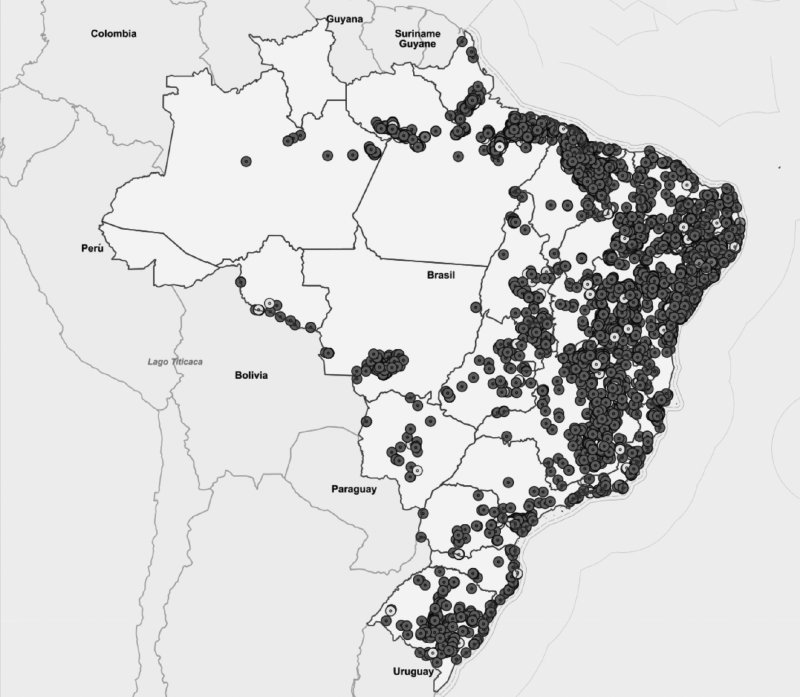

As Maps 1 and 2 reveal, Northeast Brazil is home to the largest number of quilombos, with 68.14 percent, followed by the Southeast (14.75 percent), North (14.55 percent), South (3.60 percent) and Central West (3.29 percent).22 When organized by state, as in Chart 1, the information becomes even more interesting.

Map 1. Quilombola Localities, 2022

Source: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, “Localidades quilombolas—2022,” Panorama do Censo 2022, censo2022.ibge.gov.br.

Map 2. Quilombola Populations, 2022

Source: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, “Pessoas quilombolas—2022,” Panorama do Censo 2022, censo2022.ibge.gov.br.

Chart 1. Estimate of Quilombola Localities by Federation Unit, 2019

Source: Alexandre Barros, “Against Covid-19, IBGE Anticipates Data on Indigenous Peoples and Quilombolas,” Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, April 24, 2020, ibge.gov.br.

There is a vast array of stories that might be told about the concrete lives of these communities and individuals: their spatial distribution, their legal battles for land recognition, and their self-determined territorial practices. In general, the quilombos speak for how the Latin American and Caribbean nation-states—past and present—have been constituted through the exclusion of certain social groups. They are structured in ways that relegate such groups to an ongoing struggle for recognition as citizens. In Moura’s terms, for this population, history is the process of going from “good slaves” to “bad citizens.”

According to 2024 IBGE data, Brazil’s Black (20.5 million) and mixed-race (92.1 million) populations, along with its 1.7 million Indigenous people, constitute 114.3 million of the country’s 211 million inhabitants—over half the nation. Yet their histories remain systematically erased from the official accounts of Brazil’s social formation. Rather than their authentic stories, we are fed a constant stream of racist caricatures that frame these communities as either “barbarians” of the past or “criminals” of the present. This violent misrepresentation underscores how much of Brazil’s true history remains untold.

State policy continues to shape Black lives today, just as it did in the past. Brazil’s prison system exemplifies this, enforcing exclusion, hunger, and mass incarceration. Of the over 850,000 prisoners in Brazil, 70 percent are Black, 96 percent are men, and 30 percent are detained pretrial—sometimes for up to a decade.23 The state effectively delivers death sentences, locking away those it denies rights. Each prisoner becomes a statistic while their families endure pain, abandonment, and state violence. The prison system perpetuates Brazil’s long history of violence against the poor, modernizing the whip, the gag, and the stocks for the twenty-first century.

The Brazilian prison system faithfully reproduces the logic of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century slave ships. Rebellions both inside and outside prison walls open a window on a long history of upheaval that includes the Malês Rebellion (1835), the Balaiada (1838–1841), the Cabanagem in Grão Pará (1835–1840), and O Contestado in southern Brazil (1912–1916). These uprisings should make us aware that there are surely other histories of rebellion that remain untold, the legacy of which could be deployed both in the battle of ideas and the struggle for real survival.

The twentieth century saw an upsurge of Brazilian resistance with the emergence of a major new social movement, the Landless Rural Workers’ Movement (MST), which can trace its roots to the legacy of quilombos—understood as territories of resistance and collective self-management—as well as to the experiences of Indigenous resistance.24

There is an ongoing struggle in Brazil between two models: one rooted in life-sustaining food and popular sovereignty, and the other in chemical-dependent agribusiness and superexploited labor. These two forms of production have coexisted continuously over Brazil’s history, and the persistence of the former has been a basis for resistance. However, the progressive camp, to say nothing of Brazilian society in general, has had difficulty in disseminating this history of resistance. For that reason, we need to reconstruct a clear picture of this five-hundred-year struggle against the genocide of Indigenous, Afro-Latinx, and peasant communities.

In understanding the current land struggle, the numbers speak plainly: small farms comprise 76.6 percent of rural properties yet occupy only 23 percent of arable land while producing 23 percent of gross agricultural output, and employ ten million people. Meanwhile, latifundia, vast estates dedicated to export monoculture, use over half the country’s farmland while representing a mere 1 percent of establishments.25

Final Considerations

What lessons emerge from this long history of resistance that has occurred ever since the colonial invasion, spanning the quilombos, Indigenous resistance, and today’s land struggles?

For over five hundred years, Indigenous, Afro-Latinx, and peasant resistance has persistently challenged colonial slavery and the capitalist mode of production. Their strategies of survival and struggle involved building alternative social systems capable of resolving the issue of food sovereignty while employing forms of autonomous rule.

The Brazilian state was and is a coparticipant in producing a development model that is essentially hostile to the popular classes. Why do quilombagem and other forms of resistance persist? Because the nineteenth-century republican project—in keeping with the logic of dependent capitalism—excluded these communities from the formal labor market. At best, they were relegated to the lowest salaries, leading to a racialization of poverty. Over time, these populations were rendered not just landless, but voiceless and rightless. The state served the latifundios, while developing a prison system for the landless, homeless, and lifeless.

To tell the history of resistance, we need to investigate the very territories where people live their daily lives. Indigenous communities, quilombos, and landless encampments are territories rich in oral history. By engaging with them, we can uncover alternative ways of life and explore the possibilities of overcoming the capitalist development model. Such communities, forged through centuries-long struggles for survival, are rich sources of knowledge. Popular education and popular culture must be understood as the foundations of oral history in our region.

I have attempted to highlight the profound legacy of popular power in Latin America and the Caribbean. That legacy calls upon us to listen to and build collectively alongside those who resist. Refounding the left implies correcting a historical oversight: the left, even if it understands how the enemy works, has been slow to recognize how diverse and plural popular subjects, including Indigenous, Quilombola, and peasant movements, have contributed to revolutionary processes. In our region, the revolution was and continues to be peasant, Indigenous, and Quilombola. The fundamental question is this: Are we prepared to correct the route we have taken and rechart the course in search of popular power?

Notes

- ↩ In this article, the term popular refers to the broad working class. For more discussion of the term and the conditions of the working class’s most superexploited, oppressed, and segregated segments, see Roberta Traspadini, “América Latina e o popular: Reflexões impertinentes,” Revista Emancipa no. 6 (June 2021): 96–119; Jesús Martíns-Barbero, Dos meios às medições: Comunicação, cultura e hegemonia (Rio de Janeiro: Editora UFRJ, 1987); and Paulo Freire, “Pablo Freire em Bolívia,” Fe y Pueblo Revista Ecumenica de Reflexión Teológica IV, no. 16–17 (1987).

- ↩ See Alberto Hijar, La práxis estética: dimensión estética libertária (México D.F.: Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura, 2013).

- ↩ Born in favelas and Afro-Brazilian communities, samba is a powerful vehicle for popular memory and resistance. These lyrics are from Estação Primeira de Mangueira’s winning samba theme in 2019.

- ↩ Roberta Traspadini, Questão agrária, imperialismo e dependência na América Latina (São Paulo: Editora Lutas Anticapital, 2022); Ruy Mauro Marini, The Dialectics of Dependency (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2022).

- ↩ On the European invasion, see Adolfo Gilly, Historia a contrapelo: una constelación (México D.F.: Editora Era, 2006); Miguel Leon-Portilla, Visión de los vencidos (México D.F.: UNAM, 2003); Edmundo O’Gorman, La invención de América: investigación acerca de la estructura histórica del Nuevo Mundo y del sentido de su devenir (México D.F.: Fundo de Cultura Economica, 2003); Todorov Tzvetan, A Conquista da América: a questão do outro (São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1982). An important critique of the invasion from an Indigenous perspective can be found in Aylton Krenak, Ideias para adiar o fim do mundo (São Paulo: Companhia das letras, 2019).

- ↩ For a discussion of memoricide, see Fernando Báez, A história da destruição cultural da América Latina: da conquisa à globalização (Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 2010).

- ↩ Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatístic (IBGE), Brasil 500 anos de povoamento (Rio de Jainero: IBGE, 2007).

- ↩ IBGE, Brasil 500 anos de povoamento, 46.

- ↩ Roberto Fernández Retamar, Todo Caliban (México D.F.: Viandante, 2019).

- ↩ João José Reis, “A presença negra: encontros e conflitos,” in Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, Brasil: 500 anos de povoament, 81–99.

- ↩ Luís Felipe de Alencastro, “Cotas: Parecer de Luís Felipe de Alencastro,” Fundação Perseu Abramo, March 24, 2010, fpabramo.org.br. Alencastro’s reference to “the green-gold banner of our land” comes from abolitionist poet Antonio de Castro Alves’s 1868 poem “O navio negreiro” (“The Slaveship”).

- ↩ Eduardo Galeano’s poem “Los Nadies” refers to “The nobodies…./Who don’t speak languages, but dialects/Who don’t have religions, but superstitions./Who don’t create art, but handicrafts./Who don’t have culture, but folklore./Who are not human beings, but human resources./Who do not have faces, but arms./Who do not have names, but numbers./Who do not appear in the history of the world, but in the police blotter of the local paper./The nobodies, who are not worth the bullet that kills them.”

- ↩ Guilllermo Bonfil Batalla, México Profundo: Una civilización negada (Mexico D.F.: Grijaldo, 1987).

- ↩ Clóvis Moura, Negro, de bom escravo a mau cidadão (Rio de Janeiro: Tavares & Tristão, 1977). See also Clóvis Moura, Dialética radical do Brasil negro (São Paulo: Fundação Maurício Grabois/Anita Garibaldi, 2014); and Jacob Gorender, O escravismo colonial (São Paulo: Expressão Popular e Perseu Abramo, 2016).

- ↩ See Weber Lopes Góes, Racismo e Eugenia no Pensamento Conservador Brasileiro: a proposta de povo em Renato Kehl (São Paulo: Liber Ars, 2018).

- ↩ Some of the classic works on this subject are C. L. R. James, Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution (New York: Vintage, 1989); and Eric Williams, Capitalism and Slavery (University of North Carolina Press, 1994). See also Cristiane Luiza Sabino de Souza, Racismo e luta de classes na América Latina: as veias abertas do capitalismo dependente (São Paulo: Editora Hucitec, 2020); and Marcio Faria, Clóvis Moura e o Brasil: um ensaio crítico (São Paulo: Editora Dandara, 2024).

- ↩ A recording of this samba theme can be found at SoundCloud: Edinho Carvalho, “Palmares, Um Modelo De República Popular,” soundcloud.com/edinho-carvalho-2/palmares-um-modelo-de-republica-popular-danilo-edinho-lo-re-marcio-tb.

- ↩ IBGE, “Censo 2022: Brasil possui 8.441 localidades quilombolas, 24% delas no Maranhão,” July 19, 2024.

- ↩ Moura demonstrates how, across Latin America and the Caribbean, Afro-Latinx resistance manifested in distinct forms—such as quilombos, palenques, cumbes, and so on—each shaped by the specificities of their colonial contexts. Moura, Negro, de bom escravo a mau cidadão, chapters 2 and 3.

- ↩ Clóvis Moura, Quilombos resistência ao escravismo (Piauí: EdUESPI, 2021).

- ↩ Edson Carbeuri, Quilombo dos Palmares (São Paulo: São Paulo Editora SA, 1957), 34.

- ↩ IGBE, “Censo demográfico 2022,” ibge.gov.br, accessed February 15, 2025.

- ↩ Data from “Infopen—levantamento de informações penitenciárias,” dados.mj.gov.br.

- ↩ Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST), “Nossa História,” mst.org.

- ↩ Fetaesc, Anuário estatístico da agricultura familiar 2024 (São José: Fetaesc, 2024), fetaesc.com.br.

Comments are closed.