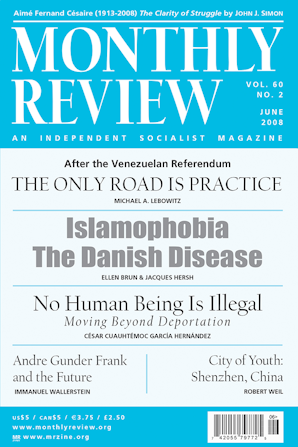

Also in this issue

Article by John J. Simon

- Sweezy v. New Hampshire: The Radicalism of Principle

- A Portrait of Gil Green

- Pete Seeger, Socialist Songster: Introduction

- The Death and Life of Che

- Rebel in the House: The Life and Times of Vito Marcantonio

- Albert Einstein, Radical: A Political Profile

- The Achievement of Malcolm X

- Leo Huberman: Radical Agitator, Socialist Teacher

- 'Unacknowledged Legislators': Poets Protest the War (Introduction)