Vietnam WAR: 50 years on

In early 1970, Vice President Spiro Agnew had this to say about the so-called ’60s Generation: “As for these deserters, malcontents, radicals, incendiaries, the civil and the uncivil disobedients among our youth, SDS, PLP, Weathermen I and Weathermen II, the revolutionary action movement, the Black United Front, Yippies, Hippies, Yahoos, Black Panthers, Lions, and Tigers alike—I would swap the whole damn zoo for a single platoon of the kind of young Americans I saw in Vietnam.” This is a fascinating statement for multiple reasons and on multiple levels. To begin with, a single platoon of the kind of young Americans he saw in Vietnam went into a village we remember as My Lai and murdered 407 unarmed men, women, and children. On the same day, in the nearby village of My Khe, another unit of the same division murdered an estimated 97 additional Vietnamese civilians. While I personally did not participate in or witness killing on that scale, I and my fellow Marines routinely killed, maimed, and abused Vietnamese on a near-daily basis, destroying homes, fields, crops, and livestock with every weapon available to us, from rifles and grenades to heavy artillery and napalm.… It is no wonder, it turns out, that Agnew should be so fond of “the kind of young Americans” he saw in Vietnam, since he himself turned out to be a criminal who was forced to resign from his office in public disgrace. | more…

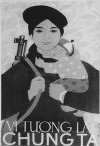

The Vietnam War was an example of imperial aggression.… Imperialism ultimately enriches the home country’s dominant class. The process involves “unspeakable repression and state terror,” and must rely repeatedly “upon armed coercion and repression.” The ultimate aim of modern U.S. imperialism is “to make the world safe” for multinational corporations.… U.S. imperial actions in Vietnam and elsewhere are often described as reflecting “national interests,” “national security,” or “national defense.” Endless U.S. wars and regime changes, however, actually represent the class interests of the powerful who own and govern the country. Noam Chomsky argues that if one wishes to understand imperial wars, therefore, “it is a good idea to begin by investigating the domestic social structure. Who sets foreign policy? What interest do these people represent? What is the domestic source of their power?” | more…

The Politics of a Forgotten History

[wcm_nonmember]

This article will be published on June 20th.

[/wcm_nonmember] It has been nearly fifty years since the height of the Vietnam War—or, as it is known in Vietnam, the American War—and yet its memory continues to loom large over U.S. politics, culture, and foreign policy. The battle to define the war’s lessons and legacies has been a proxy for larger clashes over domestic politics, national identity, and U.S. global power. One of its most debated areas has been the mass antiwar movement that achieved its greatest heights in the United States but also operated globally. Within this, and for the antiwar left especially, a major point of interest has been the history of soldier protest during the war.… Activists looked back to this history for good reason.… Soldiers, such potent symbols of U.S. patriotism, turned their guns around—metaphorically, but also, at times, literally—during a time of war. | more…

In a letter to Vietnam War veteran Charles McDuff, Major General Franklin Davis, Jr. said, “The United States Army has never condoned wanton killing or disregard for human life.” McDuff had written a letter to President Richard Nixon in January 1971, telling him that he had witnessed U.S. soldiers abusing and killing Vietnamese civilians and informing him that many My Lais had taken place during the war. He pleaded with Nixon to bring the killing to an end. The White House sent the letter to the general, and this was his reply.… McDuff’s letter and Davis’s response are quoted in Nick Turse’s Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam, the most recent book to demonstrate beyond doubt that the general’s words were a lie.… In what follows, I use Turse’s work, along with several other books, articles, and films, as scaffolds from which to construct an analysis of how the war was conducted, what its consequences have been for the Vietnamese, how the nature of the war generated ferocious opposition to it (not least by a brave core of U.S. soldiers), how the war’s history has been whitewashed, and why it is important to both know what happened in Vietnam and why we should not forget it. | more…

Leo Cawley (1944-1991) grew up in suburban south Florida and graduated from high school in Jacksonville in 1962, receiving one of two William Faulkner scholarships awarded that year by the University of Virginia, based on two short stories and three poems he had written. He had a bright future as a creative writer.… Instead, he soon he found himself in the Marine Corps and on the front lines in Vietnam, wounded in action more than once. It became the transformative experience of Cawley’s life.… It was in Vietnam that he was poisoned by the defoliant Agent Orange sprayed by the U.S. military with little regard for its own troops…. As a result, in 1980 he developed the multiple myeloma that would kill him eleven years later.… In this essay on Oliver Stone’s film Platoon, reprinted below, Cawley points out that the authors of nineteenth-century realist novels, writing in the era of the Industrial Revolution and triumphalist capitalism, sought to tell their readers what quotidian life and work was like.… The critical insights in this piece and in others demonstrate this. His perspective, at once radical and sharp, grows both from his life experience and his formidable talents. | more…