Interview by Françoise Girard for The Famous Feminist, with Ros Petchesky, coeditor, A Land With A People. (Also watch her impressive interview on Al Jazeera, here.)

On November 13, 2023, in New York City, I had the privilege of interviewing the brilliant Rosalind P. Petchesky, professor emerita of political science at Hunter College and renowned and beloved feminist activist and thinker. Ros and I first met in 1999 at the UN in New York City, during diplomatic negotiations over sexual and reproductive health and rights, and we have remained friends ever since.

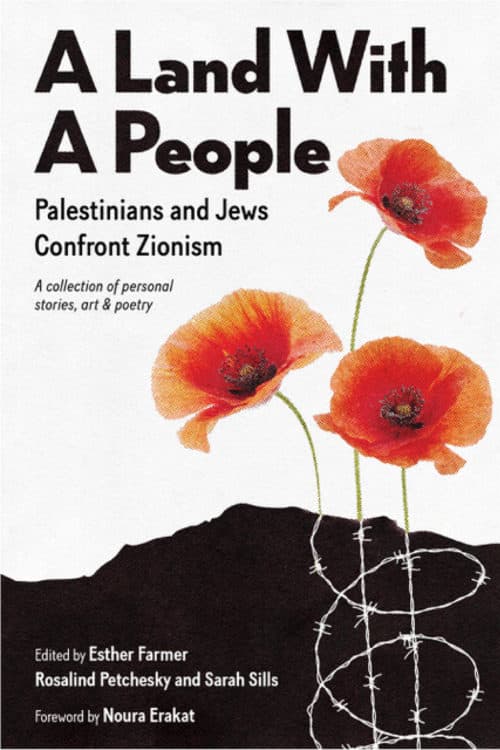

Ros is the author of many groundbreaking books and articles, including “Antiabortion, Antifeminism, and the Rise of the New Right” (1981), Abortion and Woman’s Choice: The State, Sexuality, and Reproductive Freedom (1984, revised 1990), “Phantom Towers: feminist reflections on the battle between capitalism and fundamentalist terrorism,” (2001), and “Owning and Disowning the Body: A Reflection,” (2015). She is the recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship (the “genius award”) (1995). Her latest book, edited with Esther Farmer and Sarah Sills, A Land With A People: Palestinians and Jews Confront Zionism, was published in 2021.

Over the last decade, Ros has become deeply involved with Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP), the US-based, progressive Jewish anti-Zionist activist organization. At the age of 81, she was recently arrested twice in New York City during peaceful JVP protests against the Israeli government’s bombing of Gaza and the US government support for it. Ros has thought deeply about the connections between feminism, human rights, peace, and justice in the context of Israel and Palestine. She is kind and funny but also a truth teller—someone who sees and analyzes situations with total frankness. As a result, she is often shockingly prescient, as you will see. I edited our conversation for clarity and brevity, and added some notes in brackets.

FG: As a long-time feminist author, professor and activist, you were, for most of your career, deeply engaged on issues of reproductive rights and justice, and not so much on the question of Palestine and Israel. But when you retired from teaching at Hunter College in 2013, you decided to become deeply involved with Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP). How did this come about?

RP: I actually have a story about that in A Land With A People: Palestinians and Jews Confront Zionism. I wrote the introduction, which is a history of resistance to Zionism by Jews and Palestinians. The book is mainly stories, personal stories by Palestinians and Jews about their own life experience struggling with Zionism. Abandoning it, for Jews, and suffering from it, for Palestinians. In the book, I tell my personal story about how I got involved, originally, as a 16-year-old. That was the start for me.

I grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma in a very liberal Zionist family―we would call them liberal Zionists today. We loved Israel. My father and grandmother had visited Israel. They were devoted to the idea of Israel. And I was too! I learned all about it in Sunday school. You’ve heard of programs to get Jewish kids on Birthright tours of Israel. Well, I went to Israel on a kind of precursor of Birthright, a trip with B’nai B’rith Youth. They sponsored a nine-week trip to Israel and I went with them. I was so excited I was going to Israel. I might spend my whole life there, I might fall in love, it was fantastic!

16-year old Ros driving a jeep in Israel in 1959, on a B’nai B’rith Youth trip

FG: What year was that?

RP: It was 1959. From my perspective, the historical context in which one grows up and learns is almost everything. You’re not born an activist. You’re not born with certain values. They come to you, maybe a little from your family, maybe a little from your religion, but often from the historical moment. In the US, it was the beginning of the civil rights movement. I was becoming involved and very influenced by the civil rights movement. I will spare you the story of how we went to the high school basketball game, a Black couple and a white couple together, and there was total silence as we walked in the high school gym. So, we were doing our little bit to change things.

And so, I go to Israel and I’m all excited. We’re on a kibbutz and there’s a Black man. I mean, we weren’t allowed to meet any Palestinians. I didn’t even know about Palestinians. We were just meeting different kinds of Jews. And I’m talking to this guy on the kibbutz, who was probably a Jewish man from Yemen. I didn’t know at the time. And a white woman with a distinct Brooklyn accent comes up to me and she says, “Don’t talk to him. Don’t talk to him.” And I said, “What? Why not?” She replied, “He’s African.”

That was formative. Why was she saying that? I went home to Tulsa, and I gave these talks around town about my trip. One of them was to a small group brought together by a conservative rabbi, a group of elders, and my grandparents and parents, all around the table. I’m just telling what I saw, and then I say this happened [the incident with the Black man]. I didn’t even have the word “racism” in my vocabulary then. I just said this happened, that it was very shocking to me and it didn’t at all coincide with what I thought Jewish ethics meant, which was justice and non-discrimination for everybody. An elderly woman who was there was very upset by what I had said. So, the rabbi wrote to her, “Don’t worry, don’t listen to her. She’s just a young girl. She doesn’t know what she’s talking about. I was just in Israel, and what she said is not true.”

And there you go! My anti-racism and my feminism were spurred on by that. I thought, this is hypocrisy! I was also furious at my father at the time, because he wouldn’t let me use the family car to work to integrate public accommodations [the campaign to desegregate stores, hotels, restaurants, theaters, etc. being waged by civil rights activists at the time] in Tulsa. So I was mad at all of them. I thought, never mind! I’m not ever going back to Temple or Synagogue. I’m done! [As Ros writes in A Land With A People: “My earliest feminist anger took root in this particular caldron of religion, race, ethnicity, and gendered power.”]

And when I went to [Smith] college soon thereafter, I met my mentor, the great Palestinian intellectual Ibrahim Abu-lughod. That was my first encounter, actually, with a Palestinian. He taught me international law, and I went to the Hague Academy of International Law as a junior in college. And when I was a professor at Hunter College, I had a whole group of students who were Palestinian feminists, who became my friends for life. So, Palestine solidarity was very present for me. But, I was really busy with reproductive and sexual rights, with researching, teaching, writing, and those UN conferences.

FG: You decided to become involved with JVP when you retired?

RP: I tell everybody, if you’re going to retire, you need to have a plan! I had a three-pronged plan. It was more time for Palestine solidarity work with Jewish Voice for Peace, more time for my classical piano practice, and more time for my grandchildren. But Jewish Voice for Peace has consumed more and more of my time, because the crisis has become worse and worse.

FG: Why specifically Jewish Voice, and not other, non-Jewish organizations working for peace?

RP: I had always been strongly in solidarity with Palestinians, but it took me some time to understand that speaking out as Jews, speaking out as Jews expressly, has a big impact politically. We’re saying: Jews are not united on this. Don’t just listen to the ADL [Anti-Defamation League] and AIPAC [American Israel Public Affairs Committee] and these other organizations. They are weaponizing Jewish suffering and the Holocaust to justify the more than 75 years of oppression of Palestinians. Because we don’t date the oppression, the occupation to 1967, but at least to 1948 [what Palestinians call the Nakba, or “Catastrophe”].

[By 1949, “some 80 percent of the Arab population of the territory that became the new state of Israel had been forced from their homes and lost their lands and property,” writes Rashid Khalidi in The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine. At least 720,000 of the 1.3 million Palestinians became refugees. Some of these refugees landed in Gaza.]

And for me, there’s also the experience of the young people in JVP, especially. When I first started, JVP New York was mainly elders. Now it’s people in their 20s and 30s, overwhelmingly. We are so proud of being intergenerational! But, what’s fascinating to me as an old leftist who got angry at my religion and walked away, a lapsed Jew, is the difference in their attitude toward religion. The old ones are all old leftist Marxists, who say: “Ah! Religion!” They want nothing to do with it. While the young ones all had bar mitzvahs, bat mitzvahs. Some of them read Hebrew. They go to synagogue. One of them is a young Yiddish scholar who translates books of Yiddish poetry into English.

JVP protest at Grand Central Terminal, New York City, October 27, 2023

FG: Do you think this engagement with their Jewish faith has made them different as activists?

RP: One example. We have this new song, I’m calling it the anthem of our movement now, our movement for Ceasefire and Stop The Bombing and Not In Our Name. It comes from the Old Testament, the Book of Ruth. And you’ll notice, if you look at the Old Testament, there are the five books of Moses, the Torah, which is at the front. That’s considered the real thing, you know, the Word of God. The serious stuff! And then there’s a lot more at the back, including anything to do with women. The Book of Esther. The Book of Ruth. The Book of Ruth is the story of Naomi and Ruth. Naomi is Ruth’s mother-in-law. Naomi’s husband and her two sons die. So, she’s left with these two daughters-in-law, Ruth and Orpah. And she says to the daughters-in-law: “Go back to your villages, go back to your people. I’ll be all right. Don’t worry about me.” But, Ruth says to her, “No, I will stay with you. Whither thou goest, I will go. Where thou lodgest, I will lodge. Thy people shall be my people. Thy God shall be my God.” That was my favorite text in the Old Testament when I was a kid. I loved that text.

And now they’ve made it into a song. We sang it at the [JVP demonstration at the] Statue of Liberty. We sang it when we got arrested in Grand Central Station. I was down in the jail, and there were young women in our cellblock, in adjacent cells. And the young women next to me started singing it, and we all sang it. Where you go, Palestine, I will go. Where you go, Palestine, I will go. Your people are my people. Your people are mine. I can’t sing it without crying. They took a quintessential feminist women’s solidarity text from the Old Testament and made it into an expression of solidarity between Jews and Palestinians….

FG: One of the (many) reasons I wanted to speak with you, is to hear your feminist perspective on these events in Israel, Gaza and the West Bank. I’m currently hearing and reading plenty of foreign policy perspectives, security perspectives, points of view about US interests, Israel’s interests, and so on. Yet the feminist lens and the justice lens on this situation, I think, can be really interesting and an important contribution.

RP: I think that the feminisms that would help us here, are the ones that challenge masculinist militarism at its core. The feminisms that see that every war and every, every attempt to establish a national and ethno-national supremacy or sovereignty, and even the concept of sovereignty, are fraught with male dominance. It doesn’t mean that women are not involved in those ethno-nationalist movements, even sometimes in positions of great power. Look at Golda Meir, for example. But, these movements and wars can never solve the deep conflicts and problems of communities. Never. They just make things worse. You show me one single example, where war and fighting and weapons and bombing ever resolved the underlying problems.

FG: You’re not suggesting that people shouldn’t defend themselves if they are attacked?

RP: No, absolutely not. I’m also not saying that people who are under oppression shouldn’t resist; the right to resist is built into international law. But then what are the limits? Where do you draw the line? Hamas is a good example. Hamas is a very male dominated, militaristic power structure, that saw an opportunity, not on October 7, but long before, to try to become a dominant power in the Arab world. I think that’s what they’re going for. And, of course, they had a very worthy rival in Netanyahu and his gang of fascists. So you pit these two against each other and you’ve got colossal disaster. How many lives lost? Children? Generations lost.

FG: One of the themes we hear is the severe harm being inflicted on Palestinian women and children, but it’s gone much beyond that now.

RP: I’ve never been very fond of this expression: “women and children.” All people need protection. Humans need protection. Humans! [Philosopher and gender studies scholar at Berkeley] Judith Butler writes about our precarious lives, how life is so precarious. Feminism requires that we set up social arrangements that are safe and secure as well as happy, so we are able to feed and house people, and make it possible for all people to dance and sing. That’s the feminist perspective.

I also look at the whole history of the occupation and of Zionist settler colonialism in the land of Palestine. It has very gendered effects. Always has had, even before these events. You just try giving birth or taking care of sick children, when there is a shortage of medicines and health services because of the blockade [of Gaza], or you have to go through checkpoints, and you can’t get to a hospital or a clinic, and you have to be there for hours and hours and you may never get there.

[Indeed, even before October 7, UNICEF reported that, in Gaza, as a result of the Israeli blockade in place since Hamas took over Gaza in 2007, “life expectancy is lower and infant and maternal mortality rates are higher compared to other areas in the region. There is a high prevalence of noncommunicable diseases, particularly diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases. Mental health issues among children and adults are particularly high, driven by numerous factors including recurrent hostilities. Rates of acute and chronic malnutrition are unacceptably high, particularly among children. Lack of access to clean water and sanitation is persistently a challenge.”]

FG: Are there Palestinian feminists whose work we should know about in this context?

RP: One of the Palestinian intellectuals I’d like to give visibility to, is my very dear Palestinian feminist friend, Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian. She’s going through a terrible time, I’ll say more about that. She teaches at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. She’s extraordinary. Brilliant, strong, brave. She’s gorgeous. She teaches in both the law school and the social work school. She’s best known for her work on Palestinian women and children under the settler colonial regime. Her book: Security Theology, Surveillance and the Politics of Fear is incredible. It explores the first theology—that idea that Jews had a special mandate from God, telling them that this is their land—and how security has become a second theology that no one can challenge. And what Palestinians experience in everyday life under that security regime.

Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian, professor of law at Hebrew University

More recently, Nadera has developed a concept that’s gone worldwide, called unchilding. Taking away their childhood. You can’t have a normal childhood if you’re always under threat. If soldiers are coming into your bedroom with lasers and dogs in the middle of the night, or you can’t walk to school and feel safe because soldiers are hounding you. She walks little girls to school in the morning where she lives in Jerusalem. She tries to help people whose houses are being demolished under that long time systematic policy of the Israelis, which is a form of collective punishment.

FG: On the question of gender and reproduction: in a lecture you gave in 2017 at the University of Cambridge entitled “Security As Reproduction: The Biopolitics of Walls in Israel/Palestine and Beyond,” you spoke about the sustained focus of Israel’s founders and leaders on moving the “right people” into the territory and moving out the “wrong people,” and on ensuring the reproduction of the right people. I was struck, because this is also a focus of far-right movements in the US and elsewhere.

RP: Yes. In the history of Zionism and of the state of Israel, one of the most important themes is what we could call the demographic wars. I wrote about this in A Land With A People. Before the Nakba [in 1948], that is before the establishment of the state of Israel, David Ben-Gurion [a founder of the state of Israel and its first prime minister] was talking about the forced migration of Arabs, and about bringing millions of Jews in. He was openly considering the need to use force to achieve this. In 1947, he gave a speech saying Jews needed to be 4/5 of the population of Israel. “We have to persuade the Jews who are escaping all kinds of oppression around the world to come and live here,” was the thinking. So, this idea of numbers, of bodies was very prominent in the thinking of the Zionist leaders of Israel, way back. We’re not just talking about this horrific current Netanyahu regime.

FG: So it’s people, but also land?

RP: The occupation of the land, the annexation of the land. I visited Palestine in 2017 and 2019 with an Eyewitness Palestine delegation. The difference between just those two years was astonishing. But even in 2017, I saw, “Oh, annexation is happening, it’s not just a threat. It’s happening.” It’s totally a live process. It has been, ever since they started these illegal settlements. And the settlements are illegal under international law. Totally illegal. An occupying power is supposed to protect the population. But, the government doesn’t see it that way. They see every Palestinian, even children and babies, as potential terrorists, potential enemies. This is what Nadera writes about when she writes about unchilding.

FG: Do you consider what is going on in Gaza genocide? Some people are saying that’s up for debate, that Israel’s intent hasn’t been demonstrated, or that it hasn’t yet come to that.

RP: I think there’s no question. Listen to the interview that Democracy Now did with Craig Mokhiber [former Director of the New York Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights], because it’s the most lucid explanation of why this is a textbook genocide already. Not one on the horizon. You occupy 2.2 million people, you deprive them of fuel, food, water, and you tell all the people in the north, okay, you have 24 hours to evacuate your homes, get out and go south, or we’re going to bomb you. We’re coming in here because we believe this is where Hamas has their headquarters. And they don’t say this, but they really believe that anyone who lives there is connected to Hamas. Then you bomb them when they go south. Then you close off the exit points. So they’re trapped, in what we’ve called an open-air prison for years. But now, it’s become a death trap. And you start bombing the hospitals. Now, all these people who depended on dialysis, or need surgery, or babies in incubators, they’re dying.

It has to be intentional to be considered genocide. But there’s plenty of evidence from what Ben-Gvir [Minister of National Security], Netanyahu and Smotrich [Minister of Finance] have said, happily and proudly, that that is their intention. It’s intentional.

[During an interview with Israeli Channel 12 on November 12, 2023, Ben-Gvir said, “To be clear, when they say that Hamas needs to be eliminated, it also means those who sing, those who support, and those who distribute candy, all of these are terrorists. They should all be eliminated.” In 2017, Smotrich published a “decision plan” for the Occupied Territories that foresaw annexing them into Israel under Jewish law and expelling or “handling with greater force” any Palestinian who would resist this. This month, he called on the government to “collapse the state system in Gaza.”]

FG: Are feminist organizations in Israel speaking out about this situation?

RP: There are feminist organizations in Israel that have struggled courageously over many years. Women Wage Peace. One of the hostages is Vivian Silver [who was later found to have been killed in the October 7 attacks]. She is a long time, long-time peace activist. She lived in one of the kibbutzim near the border, was friends with people in Gaza. She was helping to ferry children who were sick from Gaza into Israeli hospitals. She marched with the women’s peace movement in Israel. But anti-war feminists in Israel have not been given a platform or a voice. Their voices have been suppressed. It’s very hard to speak out. Actually, now it’s dangerous. Israel has adopted new policies [prohibiting protests against the war in Gaza]. The Knesset passed this new law where if you speak out, you can be jailed.

Nadera Shalhoub-Kerkovian recently signed a letter that over a thousand experts on childhood had signed, calling for a ceasefire, calling the operation a genocide and condemning the impact of the military operation on Palestinian children, how this war would ruin their health even if they stayed alive. Their mental health would be just shot, gone. And her administration at Hebrew University threatened her. They said, you have to retract this, you should resign your position. They didn’t say we’re firing you, but you should resign. And she started getting publicly smeared, getting hate messages. She was afraid they were going to arrest her. This just happened two weeks ago, and we all wrote letters. I wrote a letter in Mondoweiss [newsletter on Palestine] and then Judith Butler also wrote an incredible letter of support. It addresses exactly why this is a genocide and needs to be named as such.

[An excerpt from Judith Butler’s letter: “As you doubtless know, the views of Professor Shalhoub-Kevorkian comport with a number of international legal viewpoints. The Center for Constitutional Rights in New York issued a document warning that Israeli actions may well be prosecutable as acts of genocide. They write, “mass killings are one means by which genocide is committed, but that is not the only method by which a group is “destroyed” or exterminated (in whole or in part). Raphael Lemkin, the Polish-Jewish lawyer credited with coining the term, said that genocide often includes “a coordinated plan aimed at the destruction of the essential foundations of the life of national groups so that these groups wither and die like plants that have suffered a blight…. It may be accomplished by wiping out all basis of personal security, liberty, health and dignity.

You have every right to disagree with Professor Shalhoub-Kevorkian, but it is a travesty of justice to ask that she suspend her own informed viewpoint in favor of reproducing explicit state policy. That constitutes, as you surely know, an unjustifiable intervention into both academic freedom and extra-curricular rights of expression. You may not like the fact that there is a growing chorus of people who are using “genocide” to describe the horrific situation in Gaza, but then it is your obligation as representatives of a major research university to engage in the debate, and to make room for an informed discussion of the matter free of threats. Anything else is rank censorship that destroys the aims and ideals of the university itself that you are charged with safeguarding.”]

RP: And this isn’t just about Nadera’s situation. It’s about the way that military violence ushers in periods of McCarthyism and censorship. So you become afraid to speak. You’re afraid you’ll lose your job. This censorship is also happening on university campuses all over the US. Columbia University just suspended Students for Justice in Palestine and the JVP student chapter we work with.

FG: On what grounds?

RP: That they said: “from the river to the sea.” [Congresswoman] Rashida Tlaib has been attacked for the same reason. The Palestinian writer Sumaya Awad, from the Adalah Justice Project, has described what that means. So did Rashida Tlaib in Congress. From the river to the sea, Rashida said, is aspirational. And Sumaya explained, “In all this land, everyone, no matter your race, your ethnicity, your belief system, whoever you are, whatever you look like, you should all be able to be free. Nobody should be oppressed.” That’s an interpretation that many Palestinians hold. But people reply, well, when the Likud Party [the Israeli right-wing party currently led by Prime Minister Netanyahu] says “from the river to the sea,” they mean this only for Jews, just for Jews.

FG: Are you saying that because Likud has interpreted the phrase that way, people conclude that Palestinians must therefore mean “only for Palestinians?”

RP: Yes. And we reject that! That’s against our ethics. No, we don’t believe in that. We believe in universal human rights.

FG: But there must be Palestinians who mean “from the river to the sea only for Palestinians?”

RP: Hamas would be interpreting it that way. But many Palestinians, especially feminists, say, “no.” They subscribe to inclusive, abolitionist politics. I don’t think you can separate feminism, anti-militarism, anti-war, social justice, and economic justice. If they are not part and parcel of the same politics, then you’ve got something that’s too narrow and won’t be effective and won’t mobilize millions of people as we’re trying to do. That’s why we say: “Never again, for anyone.”

JVP protesters outside New York Congressman Jerrold Nadler’s Hanukkah party on December 8, 2023, demanding he support a ceasefire

At the Statue of Liberty on November 6, 2023

FG: In the lecture you gave at Cambridge University in 2017, you talked about the trip you had just taken to Israel and Palestine. And frankly, it’s incredible listening to you in 2017, talking about the wall that had been built to separate the West Bank from Israel: “The wall is porous and plastic. It’s just a symbol of protection to reassure Israelis, rather than an actual protection. In fact, Israel is not terribly secure.” And I thought, oh, my goodness, how prescient you were, because the barriers were, in fact, remarkably easy to break through on October 7, 2023. And I was wondering, how did you know, looking at that wall in 2017 that the impressive barriers meant to separate Israelis and Palestinians were in fact porous and not secure?

RP: I observed and I saw. I saw the holes in the wall. I saw the people who had found a way to climb over it. Look, I don’t want to underestimate the huge suffering and misery that the wall has caused. I met farmers who couldn’t get to their land anymore because it was on the other side. I met people whose family lived on the other side. The wall has done horrible, horrible damage. But it’s not impenetrable.

I recommend the work of the fabulous Israeli anti-Zionist architect, Eyal Weizman. He writes about the ways the Israeli Defense Forces use topography, architecture, structures, how they see the land as tiered, as not just one surface, one plane, but different planes—to dominate, and supposedly to create security.

FG: In the work of Shalhoub-Kevorkian on security, she describes the need to erase, contain, and displace the indigenous population, but also to keep them present as a threat—until they become so erased that you don’t need to bother with that anymore, I suppose. But until that is a fact, you need to keep a symbol of the threat right there. Do you think the walls and fences serve that function?

RP: Yes. That’s the “politics of fear” Nadera describes and that Zionists have used forever. Fear of the Palestinians. Without that threat, you don’t have a justification for a State that is exclusively Jewish and for its military and security apparatus, and you don’t have a justification for the U.S. sending $3.8 billion a year in military funding that the Israelis don’t even need. Zionists need the Palestinian threat.

FG: What about women in Palestine itself? Don’t they themselves face challenges within their own society in this context of violence? Shalhoub-Kervorkian writes about CPTSD, “continued post-traumatic stress disorder,” because it never ends.

RP: Everyone faces huge trauma. But Palestinian women are very political, very engaged. I mean, look at the Tamimi family. Ahed Tamimi was 16 years old when an Israeli soldier came and harassed her brother and she stood up and she slapped the soldier. She got taken to prison, then was let out. When we visited her family home in 2019, we wanted to meet her. We met her father, who’s a Palestinian leader who himself has been imprisoned countless times. He said, “Don’t just focus on her. All of our women are like that! The women are heroic. They stand up and fight.”

There’s also a very deep commitment to motherhood, to the idea of women keeping the family together and taking care of children and husbands and parents and grandparents. I remember when I visited, there was a big prisoner strike. Palestinian prisoners are always going on hunger strikes. It’s the only weapon they have. And so they have these encampments in all the towns on the West Bank, of the families supporting the prisoners. It’s mostly women, the mothers, with pictures of their sons.

RP: It also revolves around food. The preparation of food is so important. “This is how we keep our community and our families together.” I just saw on Al-Jazeera an interview with a woman in Gaza, her family had been bombed out of their home. But she was determined to make bread and she had found a hot plate. She was making these breads. She said you could get killed going to the bakery, you can’t go to the bakery. They’re bombing the bakeries. So I’m doing this. Her kids are in the street, sitting under a tarpaulin. And she’s making bread. That’s a form of heroism, you know?

The women I met when I was in the West Bank at Birzeit University in 2017, when I asked them, “Do you ever feel like you should leave?” They replied, “We stay here. We’re not leaving. This is our home.” That’s a form of resistance.

FG: What is the way forward for the future? What kind of solution do you think is possible?

RP: What’s the alternative? Commentators, the Biden Administration are going back now to the so-called two-state solution. But there’s nowhere to create a Palestinian state because the settlers have taken over so much, annexed, literally de facto annexed so much Palestinian land.

FG: You don’t think the two-state solution is possible anymore?

RP: No. It hasn’t been possible for a long, long time. But then, on the other hand, the one-state solution… I heard somebody being interviewed who said that the only thing that would make sense is a kind of federation of two different authorities. But nobody knows really what the answer is now, because it’s gone so far and it’s involved so much death and destruction. I don’t know. I don’t know. So, all we can do is say, “ceasefire now.” Just stop this. And stop funding it. So people can breathe, and think and talk, and stop dying.

FG: Stopping the killing. Yeah, that’s certainly a minimum. Are you hopeful about any aspect of this current situation?

RP: Putting on my political scientist hat, I see changes are happening and the huge, huge uprisings and marches and protests all over the world, 300,000 people the other day in London, I mean, really all over the world. Palestine is now on everyone’s lips. It’s visible. And that’s different.

You can find the full interview at Feminism Makes Us Smarter

Comments are closed.