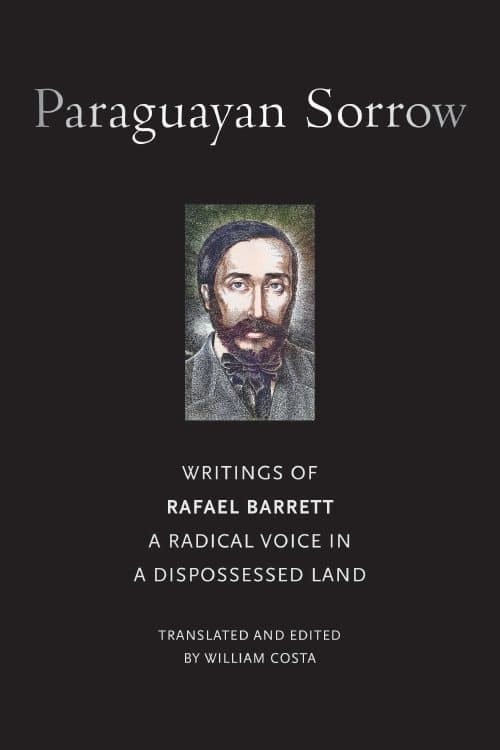

Paraguayan Sorrow:

Writings of Rafael Barrett, A Radical Voice in a Dispossessed Land

By Rafael Barrett

Translated and edited by William Costa

240 pages / $26.00 / 978-1-68590-078-6

Excerpted from:

“Hatred of Trees”

It is fine for a parvenu to build a house with money earned quickly in honest and secret business transactions. It is less fine for him to build one of those gloomy and offensive and tasteless piles of bricks, with latticed holes and tiled roof. But what makes you shudder is when he declares: “Now I’m going to pull up all the trees around the property so that it looks nice.”

Yes, the gleaming, stupid façade must look clean, bare, with its brazen colors that profane the softness of the rural tones. People must say: “This is the new house of so-and-so, that man who is now so rich.” It must be possible to contemplate the monument to so-and-so’s endeavors without obstruction. Trees are surplus to requirement: “They block the view.” And there is not only vanity in this eagerness to strip the ground: there is hatred, hatred of trees.

Is this possible? Hatred of beings that, unmoving, with their noble limbs always open, offer us the caress of their shade without ever tiring; the silent fertility of their fruits; the multifarious, exquisite poetry that they raise up to the sky? They claim that there are harmful plants. Perhaps there are, but that should not be reason to hate them. Our hatred condemns them. Our love would perhaps transform them and redeem them. Listen to one of Victor Hugo’s characters: “He saw the country’s people very busy pulling up nettles; he looked at the heap of uprooted plants that had already dried out and said: ‘This is dead. However, it would have been something good if they had known how to make use of it. When nettles are young, their leaves are an excellent vegetable; when they age, they have filaments and fibers like hemp and flax. Nettle cloth is as valuable as hemp cloth. Nettles are also an excellent fodder that can be harvested twice. And what do nettles need? Not much soil, no care, no cultivation… With a little bit of work, nettles would be useful; they are neglected, and they become harmful. So they are killed. How many men resemble nettles!’ And after a pause he added: ‘Friends, know this: there are neither bad plants nor bad men. There are only bad cultivators.’”

Oh! This is not about cultivating, but rather forgiving trees. How to placate the murderers? There is no part of the republic, of those that I have visited, in which I have not seen the property owner’s stupid axe at work. Even those people who have nothing destroy plants. Arid wasteland spreads out around shacks, getting bigger each year and causing fear and sadness. According to the Arab adage, one of the three missions of every man in this world is to plant a tree. Here, the son uproots what the father planted. And it is not about making money; I am not talking about those who harvest timber. That would be an explanation, a merit; we have come to consider greed a virtue. I am talking about those that spend money on razing the country to the ground. They are driven by a selfless hatred. And the concern grows when you see that the only works done in the plazas of the capital consist of uprooting, uprooting and uprooting trees.

This hatred is doubly cruel in a region where summer lasts eight months. The scorching sun is preferred to the sweet presence of trees. It would seem that men are no longer able to feel, to imagine the life within the venerable trunks that tremble under the iron and collapse with a pitiful crash. It would seem that they do not understand that sap is also blood and that their victims were conceived in love and light. It seems that people are enslaved by a vague terror and that they fear that the forest might harbor villains and engender ghosts. They foresee death behind the trees. Or, obsessed by a formless grief, they wish to reproduce around themselves the desolate desert of their souls.

And so, in our own souls, irritation turns to pity. Their illness must be very hopeless and run very deep. In resigned mutism, they have lost the original love, the fundamental love that even beasts feel: the sacred love of earth and trees.

[Rojo y Azul, September 27, 1907]

Excerpted from:

“Slavery and the State”

It is essential that the world know, once and for all, what is happening in the yerba mate forests. It is essential that when we want to cite a modern example of all that human greed is capable of conceiving and undertaking, we do not only speak of the Congo, but of Paraguay.

Paraguay is being depopulated; it is being castrated and exterminated on the seven or eight thousand leagues that have been handed over to the Industrial Paraguaya Company, to the Matte Larangeira, and to the tenants and owners of the great estates of Alto Paraná. The production of yerba mate rests on slavery, torture, and murder.

The facts that I am going to present in this series of articles, which is intended for reproduction in the civilized countries of America and Europe, stem from eyewitnesses, and have been cross-checked and used to confirm one another. I have not selected the most horrendous examples, but rather the things that are most common: not the exception, but the rule. And I will say to any who might doubt or deny: “Come with me to the yerba mate forests, and you will see the truth with your own eyes.”

I do not expect justice from the state. The state hurried to reinstate slavery in Paraguay after the war. This is because, back then, it possessed yerba mate forests. Here are the key parts of the decree of January 1, 1871:

“The President of the Republic.

Being aware that processors of yerba mate and of other branches of the nation’s industries continually suffer losses caused by workers who abandon their establishments with unpaid accounts…

DECREES:

…Art. 2. In all cases where a laborer needs to temporarily take leave from his work, he must obtain… consent in the form of a certificate signed by the establishment’s owner or foremen.

Art. 3. Any laborer who leaves his work without this requisite will be taken back to the establishment as a prisoner, if the employer so requests, with the costs of transport and any other expenses arising from this situation being met by the laborer.

The mechanism of slavery is as follows: the worker is never contracted without advancing him a certain amount of money, which the unfortunate man spends immediately or leaves with his family. A contract is signed before a judge in which the size of the advance is stated, stipulating that the owner will be reimbursed through work. Once driven into the jungle, the worker becomes a prisoner for the twelve or fifteen years, at most, that he will be able to bear the toil and hardships that await him. He is a slave that has sold himself. Nothing will save him. The advance has been calculated in relation to the salaries and the prices of provisions and clothing in the yerba mate forest so that the worker, even if he works himself into the ground, will always be in debt to the owners. If he tries to flee, they hunt him down. If they do not manage to bring him back alive, they kill him.

This was how it was done in Rivarola’s time. This is how it is done today.

It is well known that the state lost its yerba mate forests. Paraguayan territory was divided up among the friends of the government and then the Industrial went about taking almost everything. The state reached the extreme of giving one hundred and fifty leagues to an influential figure. That was an interesting period of selling and renting of land and buying of surveyors and judges. Nonetheless, for the moment, we are not interested in the political traditions of this nation, but in the question of slavery in the yerba mate forests.

The regulations of August 20, 1885, state:

“Art. 11. For any contract between the yerba mate producer and his workers to be enforceable, it must be signed before the respective local authority, etc.”

Not a word to specify which contracts are legal and which are not. The judge continues to give the go-ahead to slavery.

In 1901, thirty years on, Rivarola’s decree was specifically repealed. But the new decree was a novel, slyer authorization of slavery in Paraguay, given that the state no longer possessed yerba mate forests. The laborer is forbidden to leave his work, under penalty of paying damages and costs to the owners. However, the workrer is always in debt to the owner; it is not possible for him to pay, and he is lawfully captured.

The state had, and has, its inspectors, who generally become rich quickly. The inspectors go to the yerba mate forests to:

“1. Survey the entire jurisdiction of their section. 2. Inspect the production of yerba mate 3. Ensure that companies do not destroy yerba mate plants. 4. Demand that every tenant show his license for rented housing, etcetera”.

No order to verify if slavery is being practiced in the yerba mate forests, or if workers are being tortured and shot.

This legislative analysis is a little naïve, because even if slavery were not supported by law, it would be practiced anyway. The slave is as defenseless in the jungle as at the bottom of the sea.

In 1877, Mr. R. C. said that the Constitution stopped at the Jejuy River. Supposing that a worker were to extract a scrap of independence from his diseased brain and, from his aching body, the energy needed to cross immense deserts in search of a judge, he would find a judge bought off by the Industrial, the Matte, or the large estate owners of Alto Paraná. Local authorities are paid off each month with a bonus, as the accountant of the Industrial Paraguaya has confirmed to me.

So both the judge and the local official have their palms greased. They tend to simultaneously be government officials and contractors of the yerba mate companies. In this fashion, Mr. B. A., a relative of the current president of the republic, is local official of San Estanislao and a contractor of the Industrial. Mr. M., also a relative of the president, is judge in the fiefdom of Messrs. Casado and an employee of theirs. The Casados exploit the quebracho tree forests through slavery. The murder of five quebracho workers who attempted to flee in a rowboat is still remembered.

There is nothing to be hoped for from a state that restores slavery, profits from it, and retails justice. I hope I am mistaken.

And now let us turn to the factual details….

[El Diario, June 13, 1908]

Excerpted from:

“Sad Children”

It happened in a town square—a rural town like any other. It was a beautiful day; a radiant sun, a light breeze that refreshed the skin as it caressed it. The clock struck eleven and the school doors opened and out came the children. There were children of a variety of ages; some had only known how to walk for a short time, others looked like little men. There were lots of them. They were in small groups; most of them in pairs; a few stray ones. They had spent three hours sitting, motionless, mortifying themselves with the harsh stupidities of textbooks. They came out of the school in silence, their heads bowed. They did not run, they did not jump, they did not play, they did not get up to any mischief. The soft, wide lawn did not draw a single skip from them, no joyful race of young animals. The rope of the church bell reached down to the ground. Not one of them rung the bell. They were serious. They were sad.

Sad… And sad every day. Since that morning, I have paid attention to Paraguayan children, grave children that do not laugh or cry. Have you seen happy children cry? Boisterous sobbing, powerful trumpeting, half-faked, deliciously despotic sobbing that foresees mother’s exaggerated cuddles, and demands them, and knows that it is getting its way. It is half sobbing and half guffaw, a healthy scream that delights. It would comfort me to hear that sobbing in the countryside instead of mournful silence.

Here, the children do not cry: they groan or they grumble. They do not laugh, they smile. And with what wise expressions! The bitterness of life has already passed over those faces that have not started to live. These children have been born old. They have inherited the disdain and resigned skepticism of so many defrauded and oppressed generations. They begin their lives with the fatigued gesture of those that end theirs in vain.

We can measure the dejection of the campesino masses, the immemorial burden of tears and blood that weighs on their souls, through this formidable fact: the children are sad. The pressure of the national misfortune has destroyed the mysterious mechanism that renews beings; it has tarnished and adulterated love. The ghosts of the disaster of the war, and of the disaster of peace—tyranny—have haunted solitary lovers and tarnished their kisses with their mournful shadow. Spouses have shared intimacy amid distrust and ruin; they have not only trembled with passion. Voluptuousness has been left impregnated with indestructible and tragic suspicion. The torch of immortal desire holds reflections of the funeral pyre and at times seems to be a symbol of destruction and death. The parricidal work of those that enslaved the country has injured the flesh of the fatherland in its most intimate, vital, and sacred site: its sex. They have committed an outrage against mothers, they have condemned children who are yet to be born. How can we be surprised that children, the flowers of the race, do not open their petals to light and happiness! The tree has been torn up by its very roots.

Comments are closed.