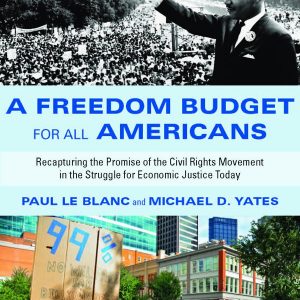

A Freedom Budget for All Americans

A Radical Vision for Victory

by PAUL BUHLE

A Freedom Budget for All Americans. By Paul LeBlanc and Michael D. Yates. New York: Monthly Review Press, 245pp, $19.95 paperback

This remarkable book brings back into view a radical vision for victory within the mainstream, armed with the kind of expectation glimpsed briefly in the 2008 election race but this time without the support of a grassroots movement long since vanished.

The Civil Rights movement, rightly called “the Freedom Movement” by participants themselves, had built up a head of steam by the 1963 March on Washington recently so much in the news again recently, for fiftieth anniversary events. But even this momentum would not likely itself have accounted for the expectation, during an extended political moment, that Democrats might boldly seek to end poverty. The impulse rested also in the surprising prestige of one very unique socialist intellectual, Michael Harrington, who with his supporters glimpsed the opportunity to apply their revolutionary visions of social transformation to the practical (or seemingly practical) prospects before them.

No political moment of the century, not even the 1930s, was quite so strange as this one. President John Kennedy, a determined Cold Warrior who created the Green Berets and promised an economic tide of profits to Wall Street dribbling down to Main Street, nevertheless proved to be a quick study in some domestic social issues. New Left leader Tom Hayden was invited to the White House (he left disappointed); the royal Kennedy couple attended a premier of Spartacus, the film purportedly breaking the Hollywood Blacklist in what we might take as a bow toward the persecuted Old Left’s cultural wing; and then there was JFK reading Harrington of The Other America, a muckraking classic about the persistence of poverty amidst plenty.

It was not all noblesse oblige. Liberal Democrats and even some Republicans were badly embarrassed at the breadth of American suffering as well as the persistence of segregation. Who knows if Jacqueline, the book reader of the family, may have been decisive here in pinpointing the author–unless it was the book’s prestige reviewer, Dwight Macdonald, at once a major recipient of intelligence agency benefits (in the global junkets of the Congress for Cultural Freedom) and simultaneously an avuncular figure urging Students for a Democratic Society, a new movement of youthful idealists, into existence.

Behind Harrington stood a remnant of the once-powerful Socialist Party, at the final moment of a sometimes glorious history. It had by this time lost its local electoral machines surviving from earlier generations, most prominently in Milwaukee, and seemed reduced to a few oversize personalities along with a youth movement. Actually, however, the SP had operatives within the veritable heart of the civil rights organizations, likewise in the Student Peace Union, in the left-leaning reform wing of the Democratic party and above all in the AFL-CIO. For a few years more, it also had Norman Thomas, “Mr. Socialism” to a generation or so of Americans. If he had no real base remaining from the almost 900,000 who cast votes for him in 1932, Thomas was likely still to be quoted in the New York Times on a variety of issues. On the labor and reform movement banquet circuit, Harrington had already been declared Thomas’s successor…

Comments are closed.