Her Majesty’s African-American Allies: A review by Gerald Horne

A review by Gerald Horne of Hannah-Rose Murray’s “Advocates of Freedom: African American Transatlantic Abolitionism in the British Isles”

It is well-established that African-Americans have sought allies abroad as a way to weaken opposition at home. Often, scholars have tackled this important topic as it manifested during the Cold War.1 The work at hand emulates previous scholarship in detailing this trend during the antebellum and early postbellum era.2 An inference that should be drawn from this historiography is that this minority group has flourished when bolstered by global allies but, alas, this conflicts with the comfortingly contrasting idea that African-Americans ever have been “patriotic” and true to Washington. This latter idea has persisted stubbornly—despite the bracing reality that it was not so long ago that Black luminaries gravitated effortlessly toward Moscow.3

Drawing heavily on British sources, Professor Murray of the University of Edinburgh focuses on the “scores of Black activists” led by the preeminent Frederick Douglass, who “traveled to England, Ireland, Scotland and even parts of rural Wales during the nineteenth century” (2). Although she does not say so explicitly, her work deftly opens the door for likeminded fruitful excavations in France, the Netherlands, Germany, and Italy—not to mention Japan, Greece, Ottoman Turkey, Ethiopia, Egypt, and elsewhere.4

She provides a roadmap for scholars so inclined to write about these nineteenth-century peregrinations. “Historians must consult a wide range of sources,” she instructs accurately, “including various forms of print ephemera (narratives, advertisements, posters, newspapers) as well as visual culture.” The industrious Professor Murray admits to having “consulted Victorian newspapers … slave narratives, pamphlets, letters, photography, children’s literature, plays, poetry, songs and even a Madame Tussaud’s exhibition catalog” (11).

The abolitionist movement, which was centered in London—and not the purported “shining city on a hill,” nor the alleged “cradle of liberty”—objectively placed Britain in an advantageous position from which it could undermine its former colony. Arguably, the very presence of these besieged African-American sojourners in Manchester and Glasgow gave resonance to Whitehall’s effort during the War of 1812 to overthrow the slaveholders’ republic or bar the annexation of the Texas Republic in 1845, or prevent the seizing of the Oregon Territory thereafter. In stentorian tones, Douglass—during his repeated journeys across the Atlantic—launched a “blistering attack on American hypocrisy. He painted America as an imperialist power that brutally oppressed his enslaved brethren…. [H]e attacked the image of America ‘as the land of the free and the home of the brave,’ especially in relation to the ‘harangues on the 4th of July’” (89).

“Between 1823 and 1831,” Murray reminds us, “2,802,773 pamphlets were written and published by the Anti-Slavery Society [U.K.] and of that number, 469,750 tracts were published in 1831 alone. Similarly, slave narratives were rapidly consumed … between 1789 and 1837, thirty-six editions of [Olaudah] Equiano’s narrative were published,” one of the renowned slave narratives of all time, which continues to be read today (26–27).

Douglass plays a leading role in this story and the author imputes to him a kind of “strategic Anglophilia” that simultaneously provided a “chastisement” of London for not traveling further down the abolitionist road (42). After all, “he found ‘the price of human flesh on the Mississippi was regulated by the price of cotton in Manchester’” (192). Deftly, “he played to Britain’s moral superiority and jingoistic pride when he stated Britain had unique and powerful influence” on the republic. Like African-American visitors before and since, Douglass marveled at the reality that he was treated better overseas, compared to the land of his birth. Bedazzled, he remarked upon arrival in Britain in 1845, “‘I am seated beside white people—I reach the hotel—I enter the same door … no one is offended.’” In sum, the rancid racism of the republic was hardly universal; it grew in the fertile and loamy soil of bigotry watered by indigenous dispossession (91). Correspondingly, this palpable difference between the republic and the monarchy encouraged the latter to disparage the former, just as the weaknesses of Moscow in the twentieth century compelled Washington to assume a posture of complacent sanctimony. Hence, the British press stoutly “referred to slavery as an American phenomenon,” especially after abolition in the Caribbean in the 1830s (156). In short, “British antislavery had become inexorably tied to patriotism,” with enormous trans-Atlantic consequences (157).

Douglass’ message was embraced in the monarchy and, like a feedback loop, encouraged him to proclaim it more loudly and insistently. “By the end of 1847, The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass had reached its ninth edition and sold more than 11,000 copies. On the eve of the Civil War, it had sold at least 30,000” (132).

Global pressure should be considered when determining how and why slavery was abolished within the republic—it was not simply a matter of the resolution of sectional conflict between North and South in the United States….

You can read the rest of Dr. Horne’s review in the journal, Diplomatic History, published by Oxford University Press

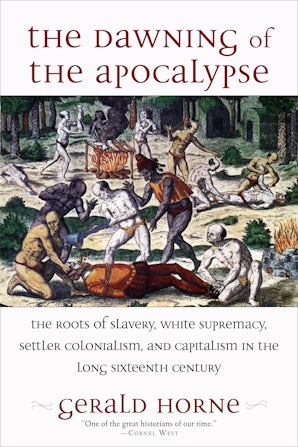

In addition to the ABA-award-winning The Dawning of the Apocalypse: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy, Settler Colonialism, and Capitalism in the Long Sixteenth Century, Gerald Horne is author of The Apocalypse of Settler Colonialism: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy, and Capitalism in Seventeenth-Century North America and the Caribbean, Jazz and Justice: Racism and the Political Economy of the Music, and Confronting Black Jacobins: The United States, the Haitian Revolution, and the Origins of the Dominican Republic, all published by Monthly Review Press.