New Politics Vol. XV No. 2, Whole Number 58

Science and Sex: Hirschfeld’s Legacy

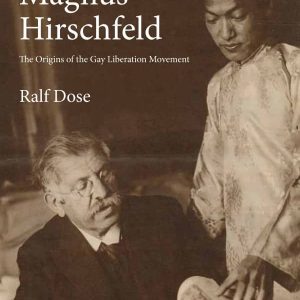

Magnus Hirschfeld: The Origins of the Gay Liberation Movement

By: Ralf Dose, translated by Edward H. Willis

Monthly Review Press, 2014. 144 pp., $23.00

Reviewed by Peter Drucker

In the mostly forgotten history of early twentieth-century movements for sexual freedom, Magnus Hirschfeld’s name is one of the most familiar—and one of the most contested. As a Jewish scientist who championed sexual deviants, he made a perfect target for the Nazis, who were tragically successful in extirpating much of his life’s work. In Western Europe today, where gay rights is virtually a civic religion, he risks becoming one of its plaster saints; the Federal Republic of Germany established an official, publicly funded Magnus Hirschfeld Foundation in 2011.

Yet proponents of very different causes can quote Hirschfeld. In the introduction to the U.S. edition of Ralf Dose’s welcome biography of Hirschfeld, Dose asserts that contemporary theorists of genetic homosexuality like Simon LeVay “can easily be located in the research tradition of Magnus Hirschfeld.” But, Dose adds, Hirschfeld’s concept of “sexual intermediacy” has attracted “an entirely new kind of interest” from queer theorists (10), who have as little use for LeVay as LeVay does for them. In short, “Hirschfeld’s is a complicated legacy” (15).

Politically, too, different currents can claim him. Clearly he was a man of the left, a socialist. Caught up in the German revolution of 1918, he became tremendously influential in the Soviet Union in the 1920s. Yet once the Nazis had consolidated their power in 1933, two years before his death, he wrote that “the three great democracies—France, England, and America”—were the world’s main hope for escaping both fascism and Bolshevism (91).

In this respect history did not fully vindicate him. France, Britain, and the United States did ultimately win World War II, putting an end to the Nazi regime. But the Allied victory did not entirely undo the Nazis’ suppression of the pre-war left and sexual liberation movements. In West Germany laws against homosexuality remained on the books until the late 1960s, and were repealed only after the shattered gay movement managed to rebuild itself. One writer observed in 1962, “For homosexuals the Third Reich has not yet come to an end” (14)…

Comments are closed.