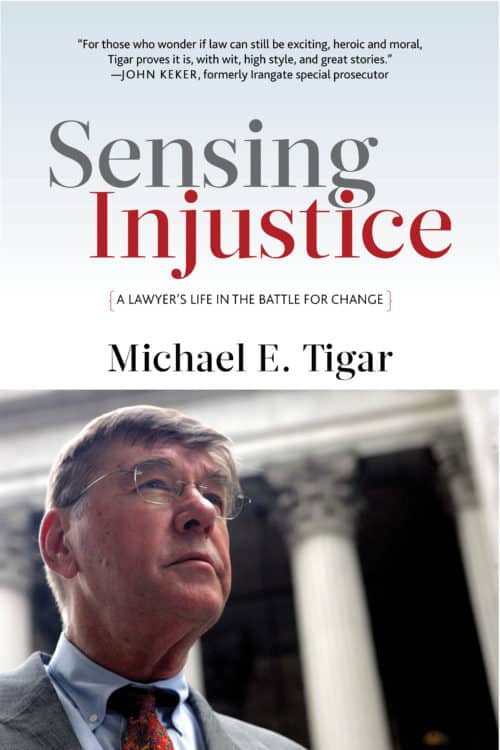

A talk given by poet Roger Reeves in honor of the launch of Michael Tigar’s book, Sensing Injustice: A Lawyer’s Life in the Battle for Change

‘You are forgetting how punctuation might change the meaning,’ says Jacobus TenBroek to his Speech 1A class at the University of California Berkley in the fall semester of 1958. Michael Tigar recollects this moment in his memoir, Sensing Injustice, a memoir that at once chronicles his coming to the field of law, his sense of justice, and his life in and out of the courts. However, this memoir also might serve as journal of his reading life, from Diderot to Dryden, from Milton to Darrow, and well, well beyond that. Or, the memoir might be a critique of law school pedagogy as well as the pedagogy of teaching high school drama. One of my favorite moments is one in which Michael critiques Mr. Farley, his high school drama teacher, for not “introducing the students to deeper issues” of spousal abuse in Susan Glaspell’s play Trifles or in Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew.

Michael’s sense of the literary, of the aesthetic is actually foundational to his sense of the law. “Looking back,” writes Michael, “I consider such storytelling [here, the storytelling he is discussing is that of O. Henry and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle] a good preparation for representing people in all social conditions in life” (41). This statement of the necessity of storytelling dovetails with what he offers earlier in his prologue: “I have striven for a view of justice shaped by the needs of clients.” I found this moment profound and underlined it several times because justice for Michael does not reside in a set of codes or conditions outside of the material and ephemeral realities of the people he serves. He understands justice to be a co-performance, a coordination, a bringing into relation. Thus, justice, redress resides not outside of those harmed but squarely with them, which for me seems to subvert and even contradict what I understand the reality of the courts and its decisions. I can’t help but think of Michael’s notion of justice as being in conversation with rhetorician and scholar Judith Butler’s notion that redress particularly for homophobia, sexism, and racism should not reside solely in the courts, in the lap of the State because often it is the State and its actors that are proliferating these injustices and injuries (i.e. the police or even Gutknecht against the United States).

Or, what occurs if the State (the courts) decide that no harm, no injury was committed? Does that mean that no injury was committed?

I’m not a lawyer, and I have, at best, a yeoman’s understanding of the law and its discourse so I will leave my critique of the courts there. However, in Michael’s brief disquisition on his sense of justice, I hear something that moves beyond the American legal system’s sense of justice, a sense of redress that centers its locus of control not merely in a set of codes or in the courts but in the people. In The State of Exception, Giorgio Agamben argues that this sort of centering is putting the people back into politics. That we live in time of a people-less politics. Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission is a great example. But again, I will leave the lawyering to the lawyers—for now.

I am here to discuss the literary merits of Michael’s work, which are substantive. In fact, I found it quite difficult to choose which one to talk about. For instance, within the first few pages of the prologue, you’re confronted with a variety of literary techniques and formal pyrotechnics. For instance, Michael starts off quoting Supreme Court records in a long citational format that teaches the reader that this memoir will take on what we in the poetry field called documentary poetics. The quoting isn’t done to merely produce evidence, but it’s to shape the reading experience, to offer a multi-voiced-ness that plays with the volley of voices that make up legal discourse and justice. It reminds me of what the Russian formalist critic Mikhail Bakhtin calls heteroglossia. Heteroglossia is the notion that there are multiple discourses in conversation and, sometimes, contestation within a book—the speech of the narrator, the speech of characters, the speech of the author. In Michael’s book, we not only listen to and are provided with the speech of the narrator (Michael), the speech of the characters, the speech of the author, but we call also get quotes from Dryden’s and Milton’s poetry, witticisms from a letter exchange with Gore Vidal, showtunes his aunt wrote, Great Depression protest songs, court testimony and record. Michael’s book literally gives us the vocal range of the American landscape. It truly is a ‘representation of people in all social conditions of life.’

A literary scholar could have a field day with this memoir, thinking through the discursive, citational practices, their political and aesthetic ramifications on the reader—what they enact. And, if I had more time, I might give such a reading. However, I want to point out something that transfixed me, meant something to me. It might seem quite small and of little importance to others, but it leapt out to my eye as a poet. It was Michael’s use of anaphora in the prologue. Anaphora is the repetition of the same word or phrase at the beginning of a line of poem. Here’s an example from Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself (please forgive the length of the quote, but I am a poet so what can I say):

Loafe with me on the grass, loose the stop from your throat,

Not words, not music or rhyme I want, not custom or lecture, not even the best,

Only the lull I like, the hum of your valvèd voice.

I mind how once we lay such a transparent summer morning,

How you settled your head athwart my hips and gently turn’d over upon me,

And parted the shirt from my bosom-bone, and plunged your tongue to my bare-stript heart,

And reach’d till you felt my beard, and reach’d till you held my feet.

Swiftly arose and spread around me the peace and knowledge that pass all the argument of the earth,

And I know that the hand of God is the promise of my own,

And I know that the spirit of God is the brother of my own,

And that all the men ever born are also my brothers, and the women my sisters and lovers,

And that a kelson of the creation is love,

And limitless are leaves stiff or drooping in the fields,

And brown ants in the little wells beneath them,

And mossy scabs of the worm fence, heap’d stones, elder, mullein and poke-weed.

We can get to the problem of Whitman’s disdainful politics surrounding race later, but you will notice the repetition of ‘And’ as if “And I know that the hand of God is the promise of my own / And I know that the spirit of God is the brother of my own….” Michael has a similar Whitmanian moment in his prologue with the word “This.” Over two pages, Michael begins several paragraphs with “this” hoping to define the dangling modifier he set out the page before when describing how he felt like he had reached the pinnacle of his career in going before the Supreme Court trying Gutknecht against the United States just two short years out from law school.

“Fifty years after that November day,” writes Michael, “I am moved to deconstruct the thought: ‘it can’t be better than this.’” In this moment of what a philologist or scholar of poetry might call correctio, Michael performs the self-reflexive, intertextual move of being in conversation with his own text as a form of revision.

This moment of revision allows him to perform his deconstruction that feels at once postmodern and quite humble. Humble in that it seeks to query his youthful assertion. Postmodern in that he drives a wedge into an opaque statement and tests its veracity. He queries the God of his youth, putting those your youthful pronouncements on trial. It’s almost a kinder, gentler killing of the author. In this case, the author is the younger version of the narrator.

But more so, the repetition of “this” creates a type of chorus, which offers a type of ritualistic return to the original phrase, the original pronouncement and ironically moves us away from it simultaneously through expansion via his meditation on what the hell he meant. Repetition, particularly, this sort of ritualistic repetition breaks the reader away from time, defies time, offering us only the present of the text. I don’t want to get into the weeds of lyric theory, but I do want to highlight the effect of the repetition of “this.” In the repetition, the “this” puts us in the time of the narrative, of the memoir. In other words, he’s taking us out of the time of our world—the world of the pandemic, the world of our busy lives—and putting us in the memoir. This sort of staging creates the opportunity for what is known as a lyric now. This lyric now creates an opportunity for transformation. It is the logic of a spell, which the logic of cooking. If I put these ingredients together (flour, sugar, egg for example) under the proper conditions (baking time, heat), we will have a cake at the end of it. That’s a spell. That’s magic. That’s the court room where lawyers volley language back and forth hoping to cause justice to come down out of the sky. In this case, the cake Michael is baking for us is ‘sensing injustice.’ He wants us to come out on the other side of this memoir, not merely witnessing a life dedicated to justice but, ourselves, ready to commit to justice to action.

In this way, I find Michael’s memoir reminding me of something the late poet Adrienne Rich wrote in a poem called “Dreamwood.” She wrote: “poetry isn’t revolution, / but a way of knowing why it must come.” In reading, Michael’s memoir I feel a similar call, a similar announcement—the memoir isn’t justice but it’s a way knowing why it must come.

Watch Roger Reeves alongside Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Jennifer Laurin, and Judge Higginbotham below, or click here to watch. Reeves starts at around 59:13 minutes in.

Pick up a copy of Sensing Injustice and receive a free ebook, full with links to Michael Tigar’s legal arguments. Become a retroactive participant in the investigative research process that Tigar himself went through.

Comments are closed.