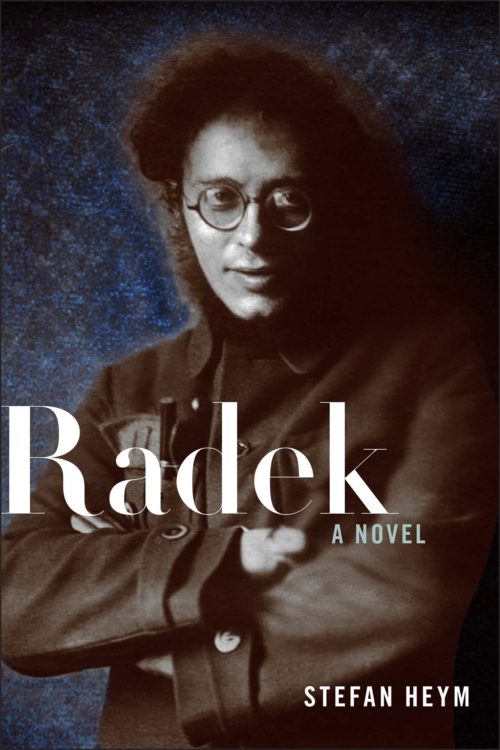

Radek: A Novel

By Stefan Heym

Translated by Alexander Locascio

$28 / 576 pages / 978-1-58367-955-5

Reviewed by John Westmoreland for Counterfire

Stefan Heym was born in Chemnitz, Germany, in 1913. As a young left-wing Jewish writer in the 1920s he constantly fell afoul of Nazi gangs and left for Berlin. There he mixed with other left intellectuals until Hitler came to power in 1933, and put an end to Heym’s hopes of a career as a writer in Germany.

Heym escaped to the USA and served with the American army on D-Day and later at the Battle of the Bulge. The Second World War ended only to be replaced by a nuclear arms race and a Cold War that shaped politics East and West. Anti-Communism in the USA took on terrifying proportions, which Heym, as a committed fighter for freedom, hated. In protest he decided to return to Germany and settled in the Communist GDR.

During the Cold War, he stood on the side of Russia, and this imposed severe limitations on his lifelong desire to see freedom in the written and spoken word. For the remainder of his life, Heym was sometimes a supporter of Stalinism and at others, an outspoken critic. He wanted, as he told an interviewer, to fight for the freedom of workers on the one hand, and against the freedom of capitalist wealth to buy, threaten and exploit on the other.

The use of Russian tanks against protesters in Hungary and Czechoslovakia saw Heym produce a number of critical works. The Communist Party valued him as a writer who could eviscerate western imperialism, but denounced his support for human rights in the GDR. Nevertheless, Heym wrote a number of political novels before the fall of the Berlin Wall that were published despite official criticism.

Heym’s own biography helps to explain why he chose Karl Radek as the central character for this historical novel. Like Heym, Radek was a literate and articulate Jew who rubbed authority the wrong way. Born Lolek Sobelsohn in Lemburg (Lviv), then under Austrian rule, Radek, like Heym, was a Marxist who became compromised as Russia went from being a beacon of revolutionary socialism to a Stalinist dictatorship. Radek helped to shape history and was also tested by it.

In life, Radek was a brilliant journalist who was active through the revolutionary years of the first quarter of the twentieth century. He was involved in revolutionary politics in Poland, Germany and Russia as well as a few other countries. He was a confidante of Lenin and helped to arrange his journey back to Russia in the sealed train. Yet, and Heym portrays this well, Radek was, as a journalist, a secondary figure in the revolutions.

After the death of Lenin and the power struggle between Stalin and Trotsky, Radek sided with the latter as part of the Left Opposition. However, after Stalin triumphed, Radek found himself in internal exile. The vacillations that Radek had displayed at crucial moments in the revolutionary years returned during his exile. Under extreme pressure, Radek denounced Trotsky and the Left Opposition and was restored to public journalism as a reward. He was then arrested during the second wave of purges and was sentenced to ten years in prison. Two of his co-defendants were shot, and Radek was himself murdered by an unknown assailant while still interned in a labour camp in 1939.

Revolutions

Radek’s life is laid out in eight books and it is a long read, but a rewarding one. My guess would be that the novel would be more compelling for someone with knowledge of the history of those years and an understanding of the Marxism of Lenin and Trotsky, and the political nature of Stalin, than for a reader unfamiliar with these things.

Heym did copious research on Radek and the portrayal of his life and times is very accurate. Radek knew virtually all the great historical figures on the left, especially in Poland and Germany. He was kicked out of both the Polish and German Social Democratic Parties before the start of the First World War for being too critical of their stuffy reformism.

Heym’s conversations between Radek and his friends and foes are very convincing and entertaining. Radek’s character is argumentative, sarcastic, brilliantly creative and analytical. Before the 1917 revolution, Radek is drawn to Lenin in terms of the political ruthlessness required to offer revolutionary strategy and tactics to the working class. He also retains a bitterness towards Rosa Luxemburg for her part in having him expelled from the SPD, and is critical of her for being too soft on the right-wing bureaucrats in the German labour movement.

If Heym is guilty of not doing justice to Luxemburg’s brilliance, he perhaps overdoes it with Lenin. The main ingredient that is missing in the novel is the working class. Lenin took Marxism from being a brilliant theory of capitalism and its contradictions to a practical engagement with the working class as the ‘gravedigger’ of the system. This involved Lenin in detailed analysis of strikes, and lengthy, often exhausting, conversations with workers. Heym keeps Lenin above the workers as the master theoretician and man of action. To some degree this is to stress the differences between Lenin and Stalin, so it’s forgivable, but unsatisfactory, nonetheless.

The post-1917 problems faced by the Bolsheviks is covered well. Radek was part of the delegation that negotiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, and he famously handed out Communist flyers to the German soldiers there. Radek worked well with Trotsky in this period, which was followed by the German Revolution. Radek knew the German comrades and got sent there as an advisor. Heym does an excellent job in portraying the immaturity of the German revolutionaries and the tragedy that unfolded in Berlin that led to the murders of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht.

It was in Germany in 1918 that Radek played the potentially most important role in life. If the German Revolution succeeded the problems assailing Russia, of trying to hold together an isolated socialist state against imperialist encirclement, could be overcome. Heym makes Radek’s intervention exciting and instructive. He combines historical fact and fictional creation to good effect and I found this section of the book utterly gripping. When Radek learns of the murders of Luxemburg and Liebknecht while in hiding in Berlin, he knows that the German revolution is lost.

Heym brings out the inner torture Radek faces as he realises that revolutionaries live on borrowed time where joy and tragedy are ever present. The inner conflicts tearing at Radek’s emotions is a recurring theme.

Radek as antihero

Heym’s portrayal of Radek as an antihero filled with inner conflict seems well-judged. He was conflicted over his love for both his wife, Rosa, who was the mainstay of his existence, and the ‘Olympian beauty’, Larissa Reissner. Reissner had been a front-line fighter and reporter in the October Revolution. Radek loved them both, and they loved him. His relations with others were also complex.

Radek was liked and admired, or despised and loathed, in equal measure. His wit was perhaps his best known quality. He used it to enrage political opponents, German officers, policemen, jailers and his accusers generally. Yet it also made him popular. He was, for a time, the editor of Izvestia, the paper of the revolution, and his articles and speeches were cleverly constructed. This made Radek attractive to politicians and foreign journalists. However, his inner conflicts prevented him from meeting the great challenges that revolutions throw up.

Trotsky, who was later to commend Radek for a ‘quarter century of revolutionary work’, also observed that his brilliance made him often too quick to judge a situation, and he would vacillate as circumstances changed. This made him a valuable, but inconsistent ally.

Heym develops this theme of Radek the antihero, unable to keep up with events as Stalin becomes the dominant force in Russian politics. Heym’s critique of Stalin is spot on. Stalin’s cautious and reactionary approach to revolutionary events in Germany in 1923 and China thereafter are thoughtfully exposed. In particular, Heym accurately frames Stalin as the arch-bureaucrat whose instinct for personal survival encourages a regime of violence and terror that, as it gathers strength, becomes a force that simply cannot be opposed.

Readers will no doubt respond to the last two books in different ways. As Radek moves towards reconciliation with Stalin, and lends his literary talents to the creation of ‘Stalin: The Great Architect’ of Communism, one feels increasingly alienated from him. And yet, Heym skilfully shows that there were really only two choices for would be oppositionists once Stalin became the undisputed ‘Boss’: a principled death or cringing submission.

Heym no doubt felt Radek’s inner conflict in a very personal way, and he makes a valiant attempt to show Radek brilliantly manipulating the prosecutor at his trial by basically writing the script for the prosecution! A valiant attempt to save some dignity for Radek certainly, but at the end of the day, a fake confession and a betrayal of the revolution is beyond a bit of polish.

Radek: A Novel, is well worth reading. I thoroughly enjoyed it. There are times when the reader with little historical knowledge will find it difficult to get along with the plot, but it is a massive story to tell through the travails of one man, and Heym does an excellent job overall. Relationships between people who made history are thoughtfully explored through dialogue rich in insights, and this makes it a very rewarding read. It will serve as an excellent introduction to the history of modern Russia for newcomers, and will stimulate thoughts anew for the cognoscenti.

Read the review at Counterfire

Comments are closed.