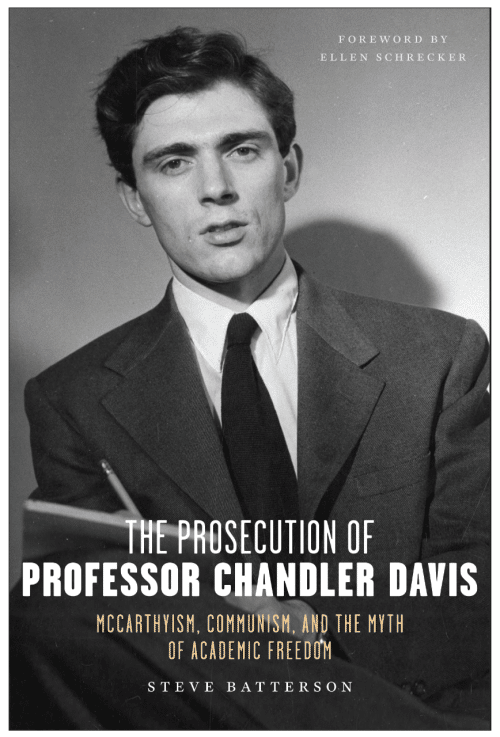

The Prosecution of Professor Chandler Davis: McCarthyism,Communism, and the Myth of Academic Freedom

by Steve Batterson

232 pages / $26 / 978-1-68590-035-9

Reviewed by Jonathan Scott Perry for The Historian

….A distinguished professor emeritus of mathematics and computer science at Emory, Batterson met Davis on a hike in Banff, Alberta, Canada, in 2010, while both were attending a workshop at a research center (or, more properly, a centre). Because he was familiar with Schrecker’s book, Batterson asked Davis whether he could pose more questions about his experience in 1953, though he would respect Davis’s wishes if the probing would make him too uncomfortable. In his recollection, Davis responded with “something to the effect: ‘Why should I be uncomfortable? I did nothing wrong’” (12-13). Over the next decade and more, Batterson interviewed both Chandler and Natalie Zemon Davis on multiple occasions, engaged in numerous email correspondences with both, and gathered as many documents, including family photographs, as he could find that touched on Davis’s life and career, up to his departure with his family to Canada in 1962.

Some of the most important chapters in the book are the ones that address the multiple career disasters and occasional triumphs experienced by both of Davis’s parents when he was a very young child. Chapter One is entitled “Red Diaper Baby,” but that familiar term masks the real sufferings of a young academic couple who were devoted to their children—but also to their political commitments and to social justice causes. Horace Davis and Marian Rubins met when both were graduate students in economics at Columbia University, but they would be unable to secure stable academic employment to provide for their growing family. By 1941, Horace Davis had been fired from four academic jobs, including one at Southwestern (the future Rhodes) College in Memphis and one in São Paulo, Brazil. In each position, he angered a powerful set of bosses with principled stands against racial and economic exploitation—and it is critical to remember that, just before his son was called before HUAC in 1953, he had been fired again, this time by the University of Kansas City (today’s University of Missouri— Kansas City).5 The general scenario is very much akin to David Maraniss’ 2019 memoir of his own father’s years of career floundering, after a 1952 hearing in Detroit led to his being fired by the Detroit Times,6 but Horace’s most recent dismissal taught Chandler a valuable lesson: relying on both the Fifth and the First Amendments for support in such a hearing would not save one’s job, and it could also lead to vilification in the press as a “Fifth Amendment Communist” (76-77).

Each of Batterson’s chapters introduces a dazzling array of legal reasoning, court maneuvering, and practical details, but the book is at its best when it focuses on Chandler Davis’s inner struggles about the correct legal and moral path to take at a given moment. While one might worry that Batterson is relying too heavily on Davis’s recollections, at a distance of more than six decades, he provides ample documentary evidence—helpfully posted on two websites—to substantiate what Davis actually said and did at the time.

Nevertheless, it was Davis’s specific training as a mathematician that Batterson is in a unique position to adduce—though, as will be explored below, Davis’s academically minded confidence in logical reasoning may have been inadequate preparation for the inquisitions he faced…

…The book under review furnishes ample proof that professional historians do not have the market cornered on rigorous historical method, and the most fascinating portions of Batterson’s brilliant book draw on reasoning methods that may be common to mathematicians but elude the practitioners of other disciplines. The resulting study is a landmark of historical (and institutional and legal) scholarship, as well as a fitting tribute to the author’s late friend, and it also provides essential reading in our own perilous times, when “academic freedom” does indeed seem “mythical”, as Batterson implies in his subtitle.

Each of Batterson’s chapters introduces a dazzling array of legal reasoning, court maneuvering, and practical details, but the book is at its best when it focuses on Chandler Davis’s inner struggles about the correct legal and moral path to take at a given moment….

Read the full review at Taylor and Francis

Comments are closed.