“We will fight from one generation to the next.” In the 1960s and 1970s we anti-imperialists in the U.S. were inspired not only by that slogan from Vietnam but even more by how they lived it with their 2000-year history of defeating a series of mighty invaders. At the same time we felt that we just might be on the cusp of world revolution in our lifetimes. Vietnam’s ability to stand up to and eventually defeat the most lethal military machine in world history was the spearhead. Dozens of revolutionary national liberation struggles were sweeping what was then called the “Third World,” today referred to as the “global South.” There was a strategy to win, as articulated by Che Guevara: to overextend and defeat the powerful imperial beast by creating “two, three, many Vietnams.” A range of radical and even revolutionary movements erupted within the U.S. and also in Europe and Japan.

Tragically, the revolutionary potential that felt so palpable then has not been realized. Imperialism employed a range of high-powered, brutal, and sophisticated counter-offensives, and our revolutionary movements were made more vulnerable to them by our own internal weaknesses.

Today, fighting from one generation to the next takes on new relevance and intense urgency. We live in a world where colossal pyramids of obscene wealth for the few cast a dark shadow on the billions of human beings who live and die without adequate nutrition, sanitation, shelter, medical care, education, or safety. On top of that unconscionable damage to lives and potential, capitalism’s ruthless war on nature has reached epic proportions, killing off thousands of species and threatening the collapse of vital ecosystems; climate change has become an existential threat to our own species. Today’s youth may be the last generation that can save the earth as a habitat for a human population of any size. The ruling class has always been very astute about learning lessons from previous periods of struggle. We who oppose them have not done nearly as well.

As dire as the current situation is, it is far from hopeless. Imperialism draws its strength from its global exploitation of labor and resources, enabling it to amass gigantic wealth and power. But that same global extension creates a vulnerability because the vast majority of the world’s 7.4 billion people have a fundamental interest in revolutionary change.

Although the corporate media whites them out from our view, there are thousands of vital grassroots struggles today—from the Rojava Revolution’s building of democracy and women’s equality within war-torn Syria to the Unist’ot’en indigenous encampment resisting Canadian tar sands and fracking projects; from workers’ strikes in China to the Mangrove Association’s fight to protect the environment in Lower Lempa, El Salvador; from community efforts to stop desertification in Kenya to women’s cooperatives reclaiming land for local food needs in the Rishi Valley of southern India; from Black Lives Matter in the U.S. to mass protests against water privatization in Italy. The greatest oppression and most advanced struggles tend to be in the global South. Internationalism, even more than a duty, is our best source of potential and hope.

By the time I was captured in 1981, I had been an anti-racist, anti-imperialist activist for 20 years. I had observed many arrests of revolutionaries. To me it always seemed critically important to draw lessons for the wider movement from any setbacks—a task greatly complicated by the way the state was ready to pounce on any self-criticism to use against defendants and their comrades. It was only when I was in that situation myself that I felt just how enormous the pressures could be. The state seeks to break you and/or put you away for life; the police are viciously hostile, the mainstream media demonize you, sectors of the Left want to use any mistakes to discredit armed struggle altogether, your family and friends want you to pull back from a political stance to mitigate the punishment the state is trying to impose on you. Pressure of geological magnitude doesn’t necessarily produce diamonds. Often the organic matter that is squeezed that way oozes out one edge or the other: either a repudiation of your past politics or a blanket defense of it all in an embattled, sectarian fashion.

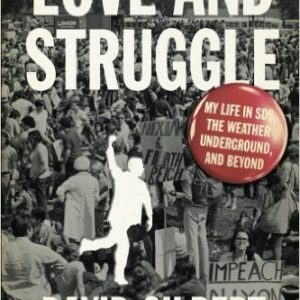

I tried to find ways firmly to uphold basic principles and at the same time analyze costly errors, not just tactically but also on a political level. Love and Struggle, published in 2012, was the slowly ripening fruit from those seeds planted after the bust.

I learned many other lessons during those years in prison. I had been involved in efforts for prisoners’ rights and especially in the development of prison peer education and support in the face of the AIDS epidemic. Nevertheless, I always saw one of my main responsibilities and passions to be political writing geared toward helping the efforts to build a movement on the outside. A number of my essays and reviews were gathered into a book, No Surrender, published in 2004. Although I have continued to write throughout my prison years, I rarely got any feedback except from close friends and the very few young activists who wrote to political prisoners. Part of the problem was that there wasn’t a very large movement out there, especially of young people who identified with anti-racist, anti-imperialist militancy. And those valiant souls who did support political prisoners did not have extensive distribution networks.

The ground began to shift at the end of 1999, after the demonstrations in Seattle against the World Trade Organization. The years that followed saw various waves of organizing and protest, including challenges to neo-liberalism, anti-war mobilizations, fights to save animals and protect the environment, indigenous-led encampments, the flowering of LGBTQ struggles, massive demonstrations for immigrants’ rights, and in 2011 the Occupy movement. While I already had a few lively correspondences, there was a significant uptick after 1999. My generation of the 1960s “New Left” had been terribly contemptuous of those who had preceded us. In a welcome contrast, this new generation, at least those who wrote me, seemed much more open to learning from our experiences. Most considered themselves anarchists but were very nonsectarian about my analytical foundation in Marxism. In turn, I could understand how they had been turned off by various organizations that called themselves Marxist-Leninist but were terribly hierarchical and sectarian. These exchanges, while still small in number, felt wonderfully worthwhile.

In 2002 I learned a striking lesson about media. While my many articles and pamphlets over the twenty years led to a couple of dozen correspondents, the release of the film The Weather Underground by Sam Green and Bill Siegel led to over 200 new people writing to me over the next three years. Ironically, of those who appear in the film, I am the most walled off from society but also the easiest for people intrigued by the film to locate and write to. Claude Marks of Freedom Archives turned outtakes from the film into a 30-minute video of interviews with me called A Lifetime of Struggle. The video was appended to the DVD version of the film, and many who wrote me were responding to that video.

As a prisoner, I have not been allowed to see the film, but I have heard from comrades that while it is good in many ways, The Weather Underground is mixed in how it presents our politics. It captures our outrage at the all-out assaults on Vietnam and on black people in the United States, but it doesn’t do as well with our sense of excitement and hope as revolutions were lighting up the world. What the young activists who wrote me most often cited was their deep appreciation of how passionate we were, and how committed to revolutionary change.

Of those more than two hundred writers, most wrote just to send a shout-out of solidarity and support. But a number of letters led to very engaged political exchanges that continue today. A few made the long trek, physically and emotionally, to visit me in prison and to go on to become good personal friends. These are not political exchanges where anyone thinks that I have all the answers, but rather very much dialogues. I’ve learned a lot about the urgency and militancy of a range of environmental actions, the importance of fighting homo- and transphobia, the emergence of a number of multiracial organizations, the use of social media. We’ve often grappled, with no clear answer, with organizational form and the problems with various examples of either democratic centralism or anarchism.

Each person who writes is different, as is each dialogue, but certain political issues recur, most especially that the key difference between the 1960s and now is not the level of atrocities, still horrendous, but the sense of hope and potential we felt back then from revolutionary upsurges around the world. A central way to counteract today’s sense of isolation is to feel a profound sense of internationalism. Other themes include the centrality of anti-racism, the necessity of fighting all forms of oppression, the need to grapple with how those play out within ourselves, the upsetting continuation of male supremacist culture and practice within activist communities, how to build a sustained movement for the long haul ahead.

As worthwhile as these correspondences are, they take a lot of time; I write close to fifty letters a month, often engaging similar issues on a one-by-one basis. When my son, Chesa Boudin, urged me to write more from personal experience (although he was referring to prison life), it clicked into place. Thus was born Love and Struggle, a memoir but with a selection process guided by what seems most relevant for activists today. It’s my story, but even more, it is their right to have a relevant history to build from. I do my best to affirm basic principles and key strengths as well as to examine, as honestly as possible, costly mistakes. While the book doesn’t have the reach and response of the film, those readers who do write go more fully into political concerns and raise more challenging questions.

This development has happened in a period of growing awareness of how the “criminal justice” system is the leading form of racism in the U.S. today, the epitome of injustice. In earlier decades there were times when movement sectarianism created a tension about whether to prioritize political prisoners or mass incarceration. In reality the two are closely linked. Many of us political prisoners, when we were free, carried out activities in solidarity with prisoners’ struggles; once captured, we became very involved in efforts for prisoners’ rights. At the same time, solidarity from other prisoners played a big role in political prisoners’ ability to survive and function on the inside. The penitentiary is an important arena where people become politically conscious and active. Overall, it is very political who is and isn’t put in prison. Many of the people who write and/or visit me have become involved, often leaders, in working on the outside for prisoners’ rights, for radically reducing incarceration, for eventually abolishing the entire punitive and oppressive system.

In the past two years, Black Lives Matter (BLM) has emerged as the most promising new development in the United States. With much of the leadership coming from young, queer, Black women, BLM has done more than anything in recent years to expose and confront the racist violence that is at the heart of what the United States is about. So far it has shown more staying power than Occupy did. I don’t know how it might develop, but I can imagine a growing synergy with efforts against mass incarceration that moves in the direction of community control and economic rebuilding for oppressed communities. It also provides a strong context for white anti-racist solidarity and the potential for identification with the targets of U.S. global aggression, mainly people of color.

Many other crucial struggles are happening in the United States and internationally. Here, I’ll highlight just two. Environmental destruction has risen to the level of an existential threat to humankind, especially with the relentless drive toward global warming. There are a range of efforts, many indigenous- or women-led, committed to turning that around.

We also face a grim political terrain of the ever-escalating and gory cycle of violence labeled as the “war on terror.” Imperialism has done so much—first in directly fostering Islamist extremist groups and then with criminal interventions that turned several countries into failed states—to generate unsavory enemies who then are used to generate public support for intensifying the warfare/security state that is the main source of these problems in the first place. This situation has made it very difficult to develop a strong antiwar and anti-intervention movement, but it is critically important to do so.

My hope for Love and Struggle is that it can be a thread to help connect different generations of activists as well as those inside and outside prison walls. More importantly, I hope all of us can weave our many threads together to create a large, sturdy, and colorful tapestry. Fighting from one generation to the next is not just an inspiring slogan but also a vital necessity for achieving a humane and sustainable world.

Comments are closed.