The increasing consolidation of the modern entertainment industry by a small clique of multinational streaming giants is the next step in what Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno call the “standardization of style” in mass-consumed art. Style is not content, nor is it form. It is above these elements; it shapes and contains them. Style is the personal manipulation of content and form by which an artist encodes their individual vision into their work. In the modern film industry, however, style is standardized with the same technocratic rationality that excuses the gross exploitation of laborers in the name of profit maximization. In the technocratic mindset, style becomes another frontier to conquer, another border to violently force into a profitable homogeneity whose structures can be relied on to generate massive revenues for the industry, while limiting the avenues by which a consumer can discover a new critical consciousness through art.

Netflix and other streaming giants are the apotheosis of the drive for a mass culture governed entirely by the logic of technocratic profit maximization. The film industry has, of course, long been controlled by profit-driven corporations that impose easily digestible story formulae onto their artists: a relatable protagonist, a charming love interest, a typical three-act structure, etc. However, Netflix’s employment of an algorithmic method as its dictator of style is the inevitable reduction of a technocratic system in which all responsibility is faithfully deferred to machinic processes that humans have imbued with infallible omnipotence. Cary Fukunaga, director of the Netflix original series Maniac, admitted as much in a press interview with GQ Magazine. “Because Netflix is a data company,” he said, “they know exactly how their viewers watch things, so they can look at something you’re writing and say, We know based on our data that if you do this, we will lose this many viewers. So it’s a different kind of note-giving. It’s not like, Let’s discuss this and maybe I’m gonna win. The algorithm’s argument is gonna win at the end of the day.” He then added: “It was an amazing exercise.… I have no doubt the algorithm will be right.”1

The Walt Disney Company, the world’s second-largest entertainment company after Comcast Corporation, has long deferred its story-making processes to artificial intelligence (AI) technologies. In 2017, the company used AI “neural networks” to scan a database of stories from the answer site Quora, interpreting upvotes as “a proxy for narrative quality” and analyzing the highest-rated posts for consistent structures and events that could explain user popularity.2 The goal of this analysis was to finetune Disney’s attempts to predict the popularity of certain content and forms. In this regard, the company has also utilized factorized variational autoencoders, or FVAEs, to film the facial responses of viewers during screenings in order to predict emotional reactions to onscreen events, and therefore use this information to generate stories that more addictively manipulate the consumer’s emotions.

Emotional manipulation is a crucial component of film, the advertising industry, and mass marketing in general, but the technocratization of this manipulation is reaching new heights with the ubiquity of behavioral analysis and cybernetic feedback technologies that seek to create “personalized viewing experiences” for their consumers. That is, in essence, viewers will be consistently fed near-identical story elements and narrative structures, and will never be challenged to engage with the content on a deeper intellectual level. William Burroughs was thus correct when he wrote that “Western man is externalizing himself in the form of gadgets,” but he might have added that this externalization—of human creativity, of emotion, of basal urges—is being managed by an exploitative upper class with the goal of efficiently extracting revenues from a passive, easily soothed populace.

It would be untruthful to say that there are not a handful of filmmakers with truly singular styles working within these structures (David Lynch may be the most prominent example), but their assimilation into streaming services is used to reify, not undermine, the dominant standardization of style. Filmmakers such as these are included as the token “weird,” “surreal,” or otherwise reductively defined artist who, as the embodiment of a particular “fringe” style, help entrench rather than subvert the degrading status quo of mainstream cultural productions.

As movie theaters have taken a blow due to COVID-19 closures and lockdown measures, and the use of streaming services becomes even more globally widespread than during the pre-pandemic era, it would not be unreasonable to assume that the future of mass entertainment will be in the algorithm-driven, AI-produced filmic products of Netflix, Disney Plus, and others. In short, streaming giants and multinational media companies will continue to subjugate content and form—style—to impersonal technologies whose only purpose is to calculate the profitability of each potential investment. Style is being ground to dust in the gears of an authoritarian mass-media technocracy. It is being weaponized to placate rather than challenge. It is being rendered totally subservient to new structures of mechanical reproducibility (or perhaps more accurately, algorithmic reproducibility), which are solely guided by increasingly sophisticated technologies of profit maximization.

The Frankfurt School understood that the logic of capital inevitably crushes all uncommodifiable elements of style and replaces them with an easily digestible product lacking in all edifying qualities. Adorno lamented that this standardization of style produced works that were anathema to great artists like Samuel Beckett and Franz Kafka, in whose work he saw a singular and irreplicable mimesis of the human condition as opposed to a rigid template of profitability. He and Horkheimer note that, in many pre-capitalist societies, works of art were revered as “magic…something spiritual, a manifestation of mana”—in the case of the modern film industry, however, all of art’s indefinable qualities have been eradicated.3 According to their historical analysis, the film industry impresses its conventions onto the consciousness of viewers in a way that reproduces but does not expand their minds: “[the films] are so constructed,” they write, “that their adequate comprehension requires a quick, observant, knowledgeable cast of mind but positively debars the spectator[s] from thinking.… [They] can be alertly consumed even in a state of distraction.”4

The productive modes by which the film industry’s commodities are deemed readily consumable by audiences, and therefore profitable for the producers, incentivize “sameness,” resulting in comforting, easily understandable films that soothe workers rather than challenging them, that totally lack that indefinable mana of the past. In this way, the sameness of the Hollywood film industry and the streaming services of today are not simply a calculation to maximize profit—they are also the means by which the capitalist system reproduces itself. “Entertainment is the prolongation of work under late capitalism,” Horkheimer and Adorno assert.5 “It is sought by those who want to escape the mechanized labor process so that they can cope with it again.” Therefore, in societies dominated by the culture industry, film represents the reproduction of capitalist labor relations through the negation of critical consciousness. “[Film] is indeed escape,” write Horkheimer and Adorno, “but not, as it claims, escape from bad reality”—it is escape from “the last thought of resisting that reality.”6

Pier Paolo Pasolini was, by nature, a person who resisted. He was an openly gay man in Italy, a country suffused with the social conservatism of the Catholic Church, and he faced down thirty-three discriminatory trials during his lifetime for charges such as blasphemy, obscenity, and contempt of religion. He was a dedicated communist intellectual in a political environment where violence, particularly of the right wing, was common, and he was one of the left’s foremost analysts of the consumer-capitalist society that emerged in the country due to the “economic miracle” of the mid–twentieth century.

Pasolini was known domestically and internationally for his incisive criticisms of Italian consumer culture, including his firm belief that postwar “neo-capitalism” had proven more harmful to the national character of Italy than the Benito Mussolini era. He believed that the neo-capitalist method of production devalued human bodies and minds to a greater extent than any previous productive mode, and that this depreciation extended to the cinematographic world as well.

Toward the end of his life, Pasolini became convinced that the increasingly ubiquitous television was the original device of postwar consumerism. Television was so harmful in his mind because it infiltrated the domestic setting. It could be played at all hours of the day. And it would, he was certain, gradually acculturate the Italian people into a fragmented, purely consumerist existence in which all drive for communal action was supplanted by the housebound sating of basal desires.

Pasolini’s early work deals primarily with the “sub-proletariat” of Rome: the forgotten young population whose indigence persisted even as the so-called miracle of postwar Italy brought a rise in national production and a drastic increase in the availability of consumer goods for the growing urban population. While the percentage of households who could afford a car or a television skyrocketed, the poverty of the sub-proletariat continued unabated. Some Italian intellectuals refer to the postwar boom in which Pasolini produced his early work not as the economic miracle, but as “the age of alienation,” emphasizing the continued poverty and worsening sense of cultural estrangement that resulted from rural dissolution, urban expansion, and demanding factory work, all of which drastically altered the population’s collective habits. Pasolini himself believed that this pervasive cultural alienation—from labor, from family, from meaningful communal undertakings—was the result of the decimation of a pre-consumerist society. Alongside other writers of his era, he argued that art should be deployed to consciously political ends—that it should be transformed into a weapon that could accurately represent the alienation of contemporary life and expose its connection to the neo-capitalist mode of production.

His distaste for postwar capitalism, however, went beyond the social alienation that it engendered. Pasolini felt that a genocide was taking place: a genocide of the “new fascism” that was destroying the old ways of life and replacing them with an exploitative and demeaning hegemony. He viewed this emergent system as more dangerous than the fascism of the early twentieth century, declaring: “I consider consumerism a worse fascism than the classical one because clerical-fascism did not transform Italians.… It was totalitarian but not totalizing.”7 He therefore believed that the new consumer culture and its artistic productions were an alienating force of unprecedented power that materially seduced individuals while manipulating their bodies and minds for the benefit of an authoritarian few. The postwar culture industry, and television in particular, did not simply represent a decrease in the quality of artistic production in Italy. Through its negation of the critical consciousness of viewers, it was also actively complicit in an authoritarian economic system.

Perhaps worst of all, Pasolini did not see a viable opposition to this “new fascism.” He famously caused a stir in the Italian left with the poem “The PCI to Young People,” in which he criticized the student movements of 1968 for not recognizing the police as misguided proletarians or themselves as ideology-oblivious and bourgeois. It was a paradoxical position that spurred much condemnation and debate: in essence, he argued that the police were working class but unable to extend solidarity beyond their material investment in a reactionary institution (much as police unions today exist principally to insulate officers from outside scrutiny rather than foster proletarian consciousness), while the radical bourgeois students were incapable of implementing radical change precisely because of their bourgeois character. He also viewed the increasing liberalism around issues of sex as largely compromised. He believed that supposedly revolutionary ideas surrounding sexual liberation were in fact influenced by the prevailing logic of consumption, and that they therefore supported rather than undermined contemporary socioeconomic conditions.

Therefore, in Pasolini’s view, the material and psychic promises of consumer goods and the culture industry were so enticing that they easily co-opted their ostensible opposition. The opposition to the new fascism lacked a truly authentic and committed adversarial energy. This is what he strove to introduce in his work: an authenticity not beholden to the profitable filmic structures that reproduced neo-capitalist hegemony. In order to fight the ascendancy of this “new fascism,” Pasolini wanted to find new and authentic ways to represent the Marxist critique in his art, and to reach the intellect of his viewers in a way that challenged rather than pacified them.

Pasolini’s post-boom films resist the dynamics of modern artistic consumption by challenging the ready-made structures of the culture industry and creating works that were, in his words, “inconsumable.” In one interview, he states that his intention is to “make products that are as inconsumable as possible.… I know that there is something inconsumable in art, and we need to stress the inconsumable quality.”8 To this end, he wanted to create a “poetic cinema” that could serve as “an instrument of resistance against the commodification of culture” described by Horkheimer and Adorno. His most important artistic technique in this regard is that of Roland Barthes’s suspended meaning.

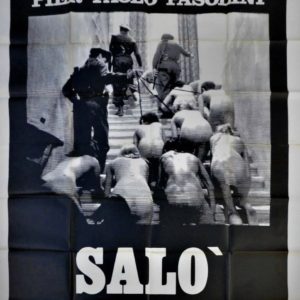

Pasolini was a documented admirer of Barthes. He quotes him directly in the essay “The End of the Avant-Garde,” and cites him in the “Essential Bibliography” title card that opens Salò. The Barthesian term that Pasolini adopts is sens suspendu, or suspended meaning. Barthes writes of suspended meaning as a theatrical practice of “uncertain signifiers” and “broken signs,” and argues that “the art and originality of the film director is situated in this zone (of broken signs).… One could say that the aesthetic value of a film is a function of the distance that the auteur knows how to introduce between the form of the sign and its content without leaving the realm of the intelligible.”9

This technique is not meant to expel meaning. Rather, it creates a sense of ambiguity in which meaning is not directly signified and is therefore suspended, refusing to provide the viewer with easily digestible symbols. Suspended meaning should be understood as an opposition to the formulaic and manipulative processes of modern cultural production as exemplified by the film industry of Pasolini’s day, and by today’s multinational streaming technocracies. Rather than producing art with the intention of manipulating consumers through predictable emotional patterns and easily understandable symbols, suspended meaning challenges easy digestibility by introducing deliberately indigestible elements to the work. By adopting this tactic, Pasolini creates a semiology of film that strives to reintroduce the “inconsumable” aspect of art—its mana—to the culture industry and awaken viewers to the totalizing structures and conventions in which they are immersed.

This strategy is present in several of his later films, particularly Teorema (1968), Porcile (1969), and Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975). The series that separates the latter two films—the Trilogy of Life, consisting of The Decameron (1971), The Canterbury Tales (1972), and Arabian Nights (1974)—is less relevant, because it is more concerned with celebrations of the body than its degradation. Furthermore, Pasolini famously disowned the trilogy before embarking on Salò, a film that more deeply explored bourgeois emptiness, aristocratic sadism, and the violence of consumerism, themes he had previously investigated in Teorema and Porcile. These three films, when analyzed as a triptych, provide important insights into Pasolini’s view of neo-capitalism and the postwar culture industry, as well as into his artistic tactics for undermining their hegemony.

The concepts of the culture industry and suspended meaning are integral to Pasolini’s artistic goals in Teorema, a film that depicts the unravelling of a bourgeois family due to the arrival of a mysterious houseguest. Pasolini stated that “a young man, maybe God, maybe the Devil, that is to say, authenticity, arrives in this family and all the characters are in crisis. The demonstration is not resolved.”10 The demonstration to which Pasolini refers is the seduction of every member of the household by the guest, who then departs, triggering a psychological breakdown in each of them. The sexual nature of their encounters should not lead one to believe that their crises are purely sexual. Their collapse is more holistic than that. The family first inhabits an agreeable socioeconomic position in which a rational hierarchy dominates, and by the end they have been seduced by the “authenticity” that bourgeois rationalism seeks to suppress, just as the mechanisms of the culture industry attempt to destroy the mana-like quality of art by forcing all creative products into reproducible structures. The fact that the family’s collective breakdown is left unresolved at the conclusion points to Pasolini’s reliance on Barthesian suspended meaning, and the ways in which he uses it to strengthen his argument for the transformative power of “authenticity.”

The guest’s role is not to offer a solution to the family’s problems; he is indigestible authenticity personified, and his purpose is to precipitate the failure of the bourgeois social body. In other words, the symbolic meaning of their collapse is suspended, and although the effects are shown, they are never unified into a singular message concerning the re-education of the bourgeoisie. Pasolini does not direct the characters or viewers toward a new belief system. This ambiguity points to his desire to reshape the plot conventions of the postwar Italian film industry, which for him always result in the destruction of art’s transformative potential. Horkheimer and Adorno note that the purpose of the culture industry’s “schema of mechanical reproducibility” is to standardize style, creating “well-worn grooves of association” that crush the mystery of the works in the uninspired machineries of rationality.11 The guest is therefore a powerful representation of the authenticity to which Pasolini himself aspires and to which he opposes the rationality of the bourgeois family, and by extension the rationality of the culture industry.

The conflict between rationalism and authenticity appears in Porcile as well, in which Pasolini again utilizes suspended meaning as a central artistic strategy. This film depicts the rise of monopoly capitalism and the failure of a truly authentic, noncommodified force to challenge this process. The film has two parallel stories. One follows a family of industrialists in postwar Germany. Over the course of the film, the family’s patriarch, Klotz, attempts to blackmail his rival, an industrialist named Herdhitze, who in turn blackmails Klotz into agreeing to a merger using information about his son Julian’s sexual obsession with pigs. It is clear from the outset that the Klotz family inhabits a different milieu than the family in Teorema: Klotz is industrial aristocracy, and his socioeconomic position is not shaken by his son’s indifference to matters of business or Julian’s girlfriend Ida, who is a participant in the radical student movements of 1968. As noted, Pasolini had already made his negative opinions of the student movements and wider sexual liberalism clear by the time he made Porcile. Therefore, authenticity as a force of change is absent from Porcile. Ida, the symbol of student radicalism, is politically bankrupt, and the most prominent representation of sexual liberalism is Julian, whose only desire is to have sex with pigs, the film’s symbol of unbridled consumption. Pasolini depicts the emptiness of student radicalism and the commodification of sexual liberalism in order to indicate the hopelessness of the situation as he sees it: the powerful have crushed authenticity via rational production, while the youth is unable to extricate itself from the consumptive patterns of the culture industry.

This analysis, however, is limited to the story of the Klotz family. The second story, which runs parallel, is that of the desert wanderer—and when paired with the story of Julian and his family, it allows Pasolini’s suspended meaning to open new pathways of intellectual analysis. The inclusion of the wanderer in Porcile is an exercise in Barthesian suspended meaning that places two unrelated stories of consumption side by side and allows viewers to form their own connections. The story depicts a nameless man trekking through a volcanic desert, consuming almost everything he encounters—plants, butterflies, humans—until he is captured and executed. His final words are: “I killed my father, I ate human flesh, and I quiver with joy.” The wanderer is clearly aligned with Julian, another figure of hedonistic consumption, but the literal nature of his consumption also relates to the discourse of industrial production that runs through the film. Excrement is used at numerous points to denote industry: “Germany,” says Klotz while speaking to Herdhitze, “what a capacity for digestion…what a capacity for defecation.” Like the cannibalistic wanderer, consumer society absorbs human beings and defecates their bodies as products for others to consume. It does not matter to Pasolini how aware one is of their own complicity, whether they “quiver with joy” or think themselves radical: they are equally guilty of glutting themselves on the exploitative excrement of neo-capitalism, and the pairing of the two stories allows viewers to form this connection. Pasolini’s most infamous condemnation of consumer-capitalist culture, however, would come six years later with Salò, in which he brutally demonstrates the ways in which consumerism violates human bodies and minds in order to satisfy its own greed.

Salò is Pasolini’s final, unflinching indictment of the consumer-capitalist culture he sought to expose over the course of his career. The film depicts four fascist aristocrats in 1945 Italy who, as their government crumbles around them, retire to a mansion in the countryside and subject a group of young men and women to brutal, often sexual, torture. The sexual violence in the film is metaphorical; as Pasolini said, “In [Salò]…sex is nothing but an allegory of the commodification of bodies at the hands of power. I think that consumerism manipulates and violates bodies as much as Nazism did.”12 His decision to represent this commodification as horrifically as possible recalls Adorno’s writings on the representation of “classical” fascism. Adorno criticized satires of fascist dictators because “the true horror is conjured away; [fascism] is no longer the slow end-product of the concentration of social power, but mere hazard, like an accident.”13

The violence of Salò is meant to communicate Pasolini’s complete antipathy toward the mental and physical effects of an increasingly monolithic culture industry, and the “slow end-product” of its standardization of style. It is a film of profound despondency. There is no suggestion of a transformative political or artistic authenticity, and the only time a character raises his arm in opposition, he is immediately gunned down. The film’s structure emphasizes this. As Thomas Peterson writes, it is “organized in an atomized and fragmented fashion [and] a continuous series of outrages of nature represses unity and mental coherence.”14

In his representation of fascist violence, Pasolini thus refuses to abide by the “well-worn grooves” of culture industry structure: the cruelty itself seems to guide the film. His unblinking focus on this torture is meant to communicate the “end-product” of “a hyper-consuming society which reifie[s] all human beings as merchandise in their own bodies.”15 It is a society governed by the structures and conventions of the culture industry, a world in which ideas, products, and people are viewed by the capitalist subject as, in Georg Lukács’s words, “things which he can ‘own’ or ‘dispose of.’”16 It is through this emphasis on rampant, heartless consumerism that Pasolini connects the content of his film to contemporary Italy, utilizing Barthes’s suspended meaning to draw viewers into this realization.

The Barthesian dimension of Salò relies on the transposition of the film’s historical setting with the present. At multiple points, Pasolini deliberately subverts his film’s historical verisimilitude by having characters quote from non-contemporary texts, and even includes a lengthy sequence in which the female storytellers perform a scene from the 1974 film Femmes femmes. As with Porcile’s juxtaposition of the Klotz family with the wandering cannibal, Salò presents a number of similarities between the film’s stated setting and 1975 Italian society, but never fully elucidates their relationship. The fascist aristocrats force-feeding feces to their captives recall Klotz’s comparison of postwar industrial productions to excrement: the modern viewer, like the film’s Second World War-era captives, is trapped by an increasingly monopolistic culture industry that extracts value from its citizens by “defecating” products lacking in all edifying qualities and forcing viewers to consume them for the industry’s benefit. This temporal overlay results in a defamiliarization of setting and joins the film to the present, hopefully making viewers consider the demeaning nature of the culture industry in relation to the violence of fascist Italy and thus form a critical consciousness regarding the degrading cultural products of neo-capitalist Italy.

Pasolini saw the postwar transformation of Italian society as a continuation, not a triumph over, early twentieth century fascism—and, most concerningly, he did not see his fellow Italians resisting the privatization of their lives. Furthermore, the advent of the culture industry increasingly turned film into an extension of the coldly rationalistic processes that governed this monopolistic economy. Pasolini employed his artistic talents in the fight against this standardization of style and used techniques such as Barthes’s sens suspendu to create “inconsumable” films that encouraged his viewers to deepen their intellectual engagement with his works. By honing his style of filmic inconsumability, he sought to increase his audience’s consciousness regarding the adverse effects of a world ruled by neo-capitalism—a world in which rationality is valued over indefinable authenticity, and profit maximization has led to a widespread standardization of style in popular art.

It would not be overly pessimistic to view the technocratic filmic productions of Netflix, Disney, and others as the modern embodiment of Pasolini’s fear of an art totally devoid of authenticity, and therefore an art completely captured by contemporary capitalism. His attempts to insert an inconsumable art into his post-boom films was a conscious political project, but the sordid manipulation of bodies and minds whose horror he sought to represent is now occurring on a much larger scale. Through an increasingly automated production process, these companies seek to subjugate the film industry’s last remnants of individual style to their bottom line. They are presently enacting the horrors of Salò across the globe. The first step the left can take toward repairing the damage is to simply stop watching, or, at least, to watch critically.

Notes

- ↩ Zach Baron, “Cary Fukunaga Doesn’t Mind Taking Notes from Netflix’s Algorithm,” GQ, August 27, 2018.

- ↩ Disney Research, “A Good Read: AI Evaluates Quality of Short Stories,” EurekAlert, August 21, 2017.

- ↩ Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002), 13.

- ↩ Horkheimer and Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment, 100.

- ↩ Horkheimer and Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment, 109.

- ↩ Horkheimer and Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment, 116.

- ↩ Celluloid Liberation Front, “The Lost Pasolini Interview,” MUBI, January 17, 2012.

- ↩ Simona Bondavalli, “Lost in the Pig House: Vision and Consumption in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s ‘Porcile,’” Italica 87, no. 3 (2010): 408.

- ↩ Elena Oxman, “Sensing the Image: Roland Barthes and the Affect of the Visual,” SubStance 39, no. 2 (2010): 75.

- ↩ “Pasolini Introduction,” Special Features: Teorema, Criterion Collection, 1975.

- ↩ Horkheimer and Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment, 100, 109.

- ↩ Celluloid Liberation Front. “The Lost Pasolini Interview.”

- ↩ Theodor Adorno, “Commitment,” in Marxist Literary Theory, ed. Terry Eagleton and Drew Milne (Hoboken: Blackwell, 2002), 193.

- ↩ Thomas E. Peterson, “The Allegory of Repression in Teorema and Salò,” Italica 73, no. 2 (1996): 224, 228.

- ↩ Peterson, “The Allegory of Repression in Teorema and Salò,” 217.

- ↩ Peterson, “The Allegory of Repression in Teorema and Salò,” 216.

Comments are closed.