Also in this issue

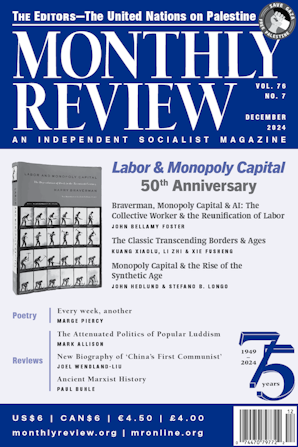

- December 2024 (Volume 76, Number 7)

- Braverman, Monopoly Capital, and AI: The Collective Worker and the Reunification of Labor

- Monopoly Capital and the Rise of the Synthetic Age

- Every week, another

- Preface to the German Edition of Marx’s Ecology

- The Attenuated Politics of Popular Luddism

- New Biography of “China’s First Communist” Reveals Nuances for English-Speaking Readers

- Ancient Marxist History