Paul Peart-Smith’s adaptation and illumination of Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s iconic study throws fresh light upon the subject matter, directly, but also subtly. The strikingly novel historical narrative revealed, and in some ways, actually created by Dunbar-Ortiz, can be seen and understood in yet another way through visualization—the choreography of images thrown up by history but rendered politically. We “understand” the totality of Indigenous life, its devastation, and the struggles to recover and rebuild, by sinking ourselves into the images. This is no small thing.

A useful irony may be found in the rise of graphic art and the depiction of the colonization process, because the illustration and romanticization of empire has been so central throughout. As Dunbar-Ortiz hints in her own introduction, the very “newness” of the “New World” implies a nonexistence of a previous history, or even palpable existence.

Long before the creation of comic art, and as early as the 1730s, “Columbia,” offered the token of “Miss Columbia,” a virginal maiden seemingly awaiting a master. Centuries earlier, reports from Central and South America inspired the artistic creation of a semi-clothed female creature, at once more savage and on those grounds more libidinal. That Christopher Columbus himself never set foot in North America proved no great hindrance to visual myth-creation.

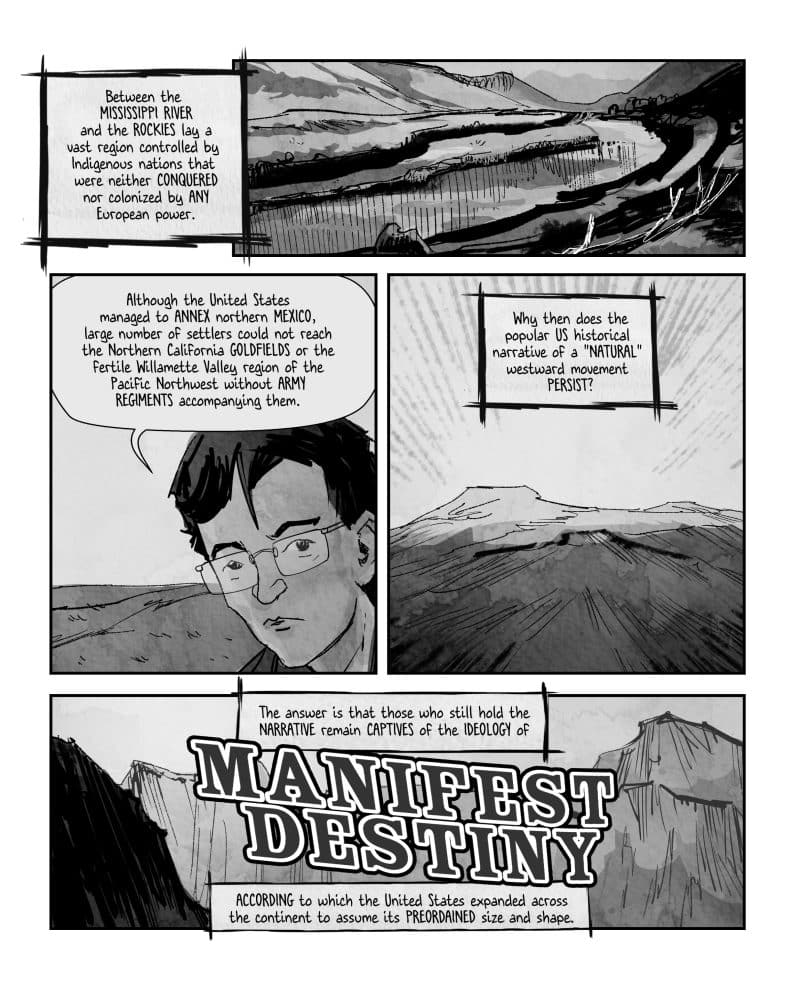

In the iconography of the new American Republic fresh from the Revolution, however, a growing cult of neoclassicism embraced Roman civilization. The heraldic eagle, the symbol of nature’s own conquering avian, offered the visual counterpart to the language of the “Senate,” as in the Roman Senate, ruling supreme upon a newly created “Capitol Hill.” These were myths on top of myths, with all the firmness of empire, as well as race and gender, intact.

By no surprise, popular illustrators of the nineteenth century—all the more popular when the invention of the inexpensive magazine funded by advertising allowed vast sales at low prices—hit the same notes. From the sheet music for “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean,” to the battling gendered icons of the Gilded Age political parties, a rising American “civilization,” often seen counterposed to its “primitive” opposites, reinforced a message that did not require elucidation. Every reader could recognize the deeper meaning.

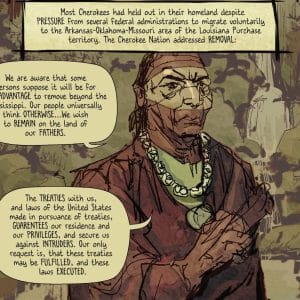

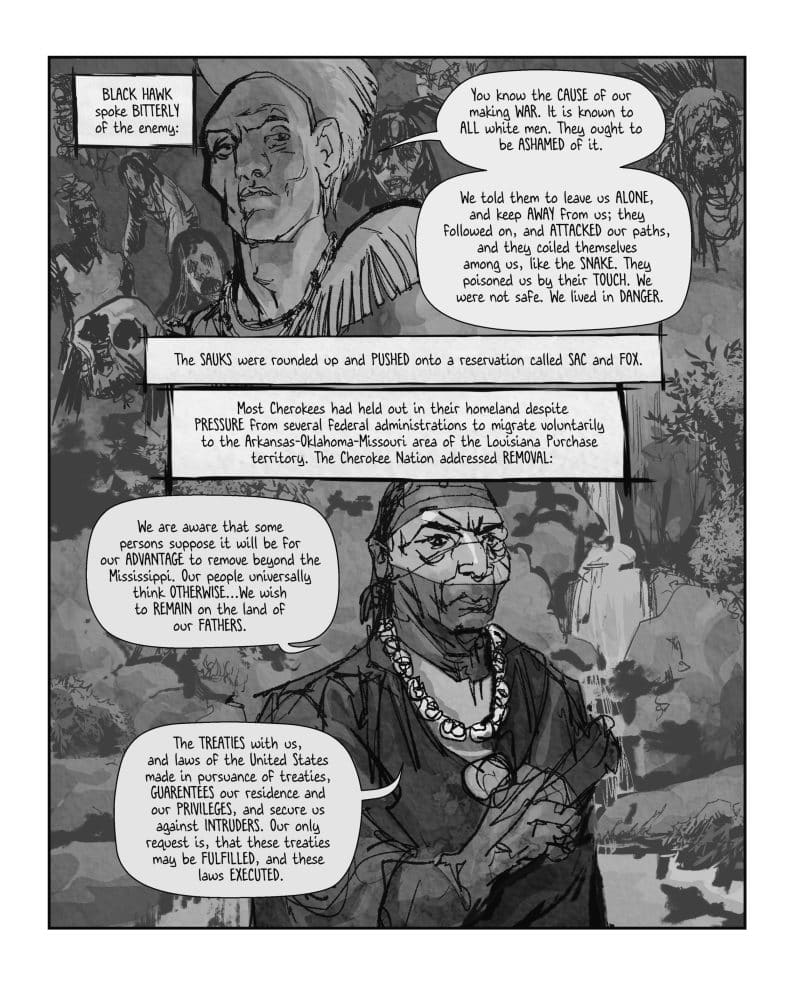

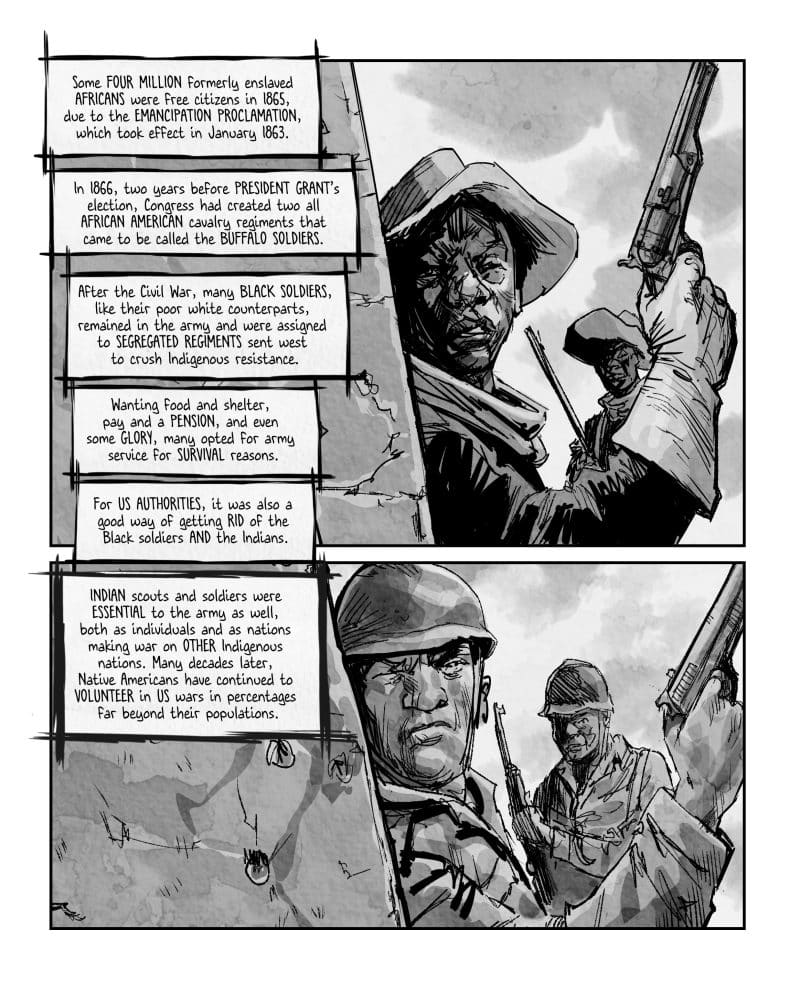

Illustrator Paul Peart-Smith explores a meaning central to the whole saga. The “Vanishing American” or the “Disappearing Red Man,” the emergence of which betokened an endless series of artful or unartful renderings that revealed or made real a collective wishful thinking. This might be viewed as almost benign when contrasted to the minstrel-like, racist caricatures of Black people or the nonwhite populations destined for conquest in Cuba and the Philippines of the Spanish-American War. But they were not at all benign, of course. Peart-Smith’s visual investigation complements Dunbar-Ortiz’s historical retelling from below: resistance to the myths and facts of extinction, termination, and assimilation; necessary practical acts of combativeness; and the development of collective, on-the-ground cultures of solidarity. Comic art could not but reflect this itinerary, which we are able to appreciate more fully today.

But the barriers to entry were high. One could easily describe the emergence of the newspaper comic strip, with the rich ethnic humor of the early twentieth century, as a process tending, easily enough from the 1920s to the ’40s, toward the narrative strips of overseas adventures and global conquest. Families, perhaps fathers and sons the most, enjoyed the Phantom, Tarzan in “darkest Africa,” Alley Oop in a distant geological past, and eventually Terry and the Pirates ranging across the globe, often confronting but always evading the mortal dangers of white noncivilization.

Historians of comic art have described how “the Western,” from the “yellow-back” or pulp novel of the 1840s onward, immeasurably deepened and extended the visual stereotypes. This applies not only to those in the United States, but for the world market of graphic narratives, which proliferated globally. From the dangerous Natives menacing wagon trains advancing West to the tribes kept under control by the courage of armies in the armored forts, civilization battled noncivilization. Increasingly, the “Good Indian” made an appearance, most vividly in the Lone Ranger’s Tonto, illuminating the recalcitrant presence of the Native “off the reservation.”

The actual depiction of Native Americans may be said to have taken another course, or the start of another course, in the same location as other comic art that was “coming of age.” That is, within the realm of EC Comics in the early 1950s, where antiracist “preachies” offered glimpses of an advanced narrative, the higher art form achieved by a handful of scriptwriters, artists, inkers, and so on, more than touched upon Natives.

The singularly great comics editor-artist, Harvey Kurtzman, guided a “Frontline Combat” series, in which Natives battling whites on the frontier achieved a remarkable dignity and realism. In other renowned EC comics created by Kurtzman, the sufferings of soldiers on both sides of the Korean War and of the civilians trapped between them could be seen clearly, a sight entirely contrary to the prowar propaganda of the time. Within the U.S. frontier stories, no less violent conflict offered a glimpse of Native life, if not the larger dispossession that made “the winning of the West” a vast human rights disaster. Thus, a popular audience, even within the McCarthyite Era of severe political repression, could see and understand the plight of Indigenous peoples.

The “Underground Comix,” or rather the work of one artist in particular, moved the needle in remarkable ways. Jack Jackson (working under his artistic name, Jaxon), a native Texan who moved with fellow artist Gilbert Shelton and a handful of others to the Bay Area, center of the counterculture in the early 1970s, returned home to set himself on his real life’s work. Jackson’s comics about Texas history or “prehistory” offered no cheerful look at dispossession, conflict, and slaughter, or at the political leadership emerging to congratulate itself by concocting its own version of history. A Lifetime Fellow of the Texas Historical Society, Jackson was inducted into the Texas Institute of Letters before his death in 2006. Within the emerging world of graphic novels (a term first widely heard when the Pulitzer Prize was awarded to Art Spiegelman in 1994), Jackson’s historically accurate nonfiction work set important precedents.

The Native contribution in the comic domain has been slow to materialize, but can be seen more and more from the 2010s up to today. Notable is Native American Classics (Eureka Productions, 2013), a far-ranging anthology with many Native contributors (and others) as artists, writers, and sources in nineteenth-century literature. Meanwhile, the centuries-old tradition of “ledger art” among Plains Natives—the work of Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Oglala Lakota members and artists—both within its recovered origins and later revivals, offers genuine parallels. Containing pictorial depictions of resistance to dispossession alongside narratives integrated within the panorama of Indigenous lifeways, this art form has provided fertile ground for continued experimentation.

Black Elk Speaks, featuring Standing Bear’s unforgettable, experience-rooted illustrations of the Battle of Little Bighorn, published in 1932, found its destiny as a bestseller only after its republication in the 1960s. Likewise, the status of contemporary works is remarkably open. Many artists have drawn inspiration from the struggles at Standing Rock, as the #NODAPL struggle once again thrust the project of Indigenous insurgency and sovereignty onto a mass stage. Now, struggle once again has prompted a renewed interest in Indigenous artistry. Present and future generations of Indigenous cartoonists, comic writers, and graphic artists will likewise find inspiration in the graphic novel artwork of the book.

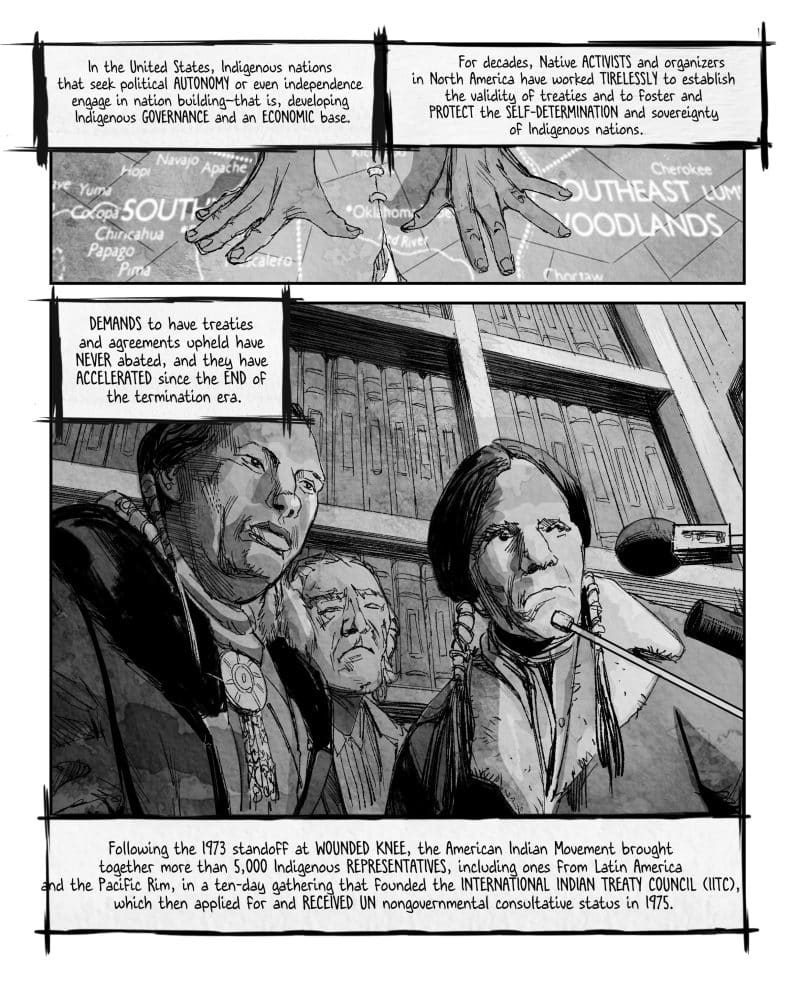

The Red Power movement in the 1960s turned hitherto dominant anti-Native tropes on their head, providing a template for the politics of self-determination that continues to this day. What events, organizations, or forces might illuminate a new path for action anchored in the transformation of society today?

Comments are closed.