Also in this issue

- Surveillance Capitalism: Monopoly-Finance Capital, the Military-Industrial Complex, and the Digital Age

- Electronic Communications Surveillance

- The New Surveillance Normal: NSA and Corporate Surveillance in the Age of Global Capitalism

- The Zombie Bill: The Corporate Security Campaign That Would Not Die

- Surveillance and Scandal: Weapons in an Emerging Array for U.S. Global Power

- We're Profiteers: How Military Contractors Reap Billions from U.S. Military Bases Overseas

- U.S. Control of the Internet: Problems Facing the Movement to International Governance

- Merging the Law of War with Criminal Law: France and the United States

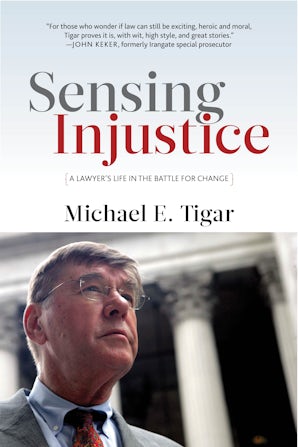

Books by Michael E. Tigar

Sensing Injustice

by Michael E. Tigar