Also in this issue

- Beyond the Degradation of Labor: Braverman and the Structure of the U.S. Working Class

- The Emergence of Marx's Critique of Modern Agriculture: Ecological Insights from His Excerpt Notebooks

- Vietnam War Era Journeys: Recovering Histories of Internationalism

- A Defining Moment: The Historical Legacy of the 1953 Iran Coup

Books by Paul Buhle

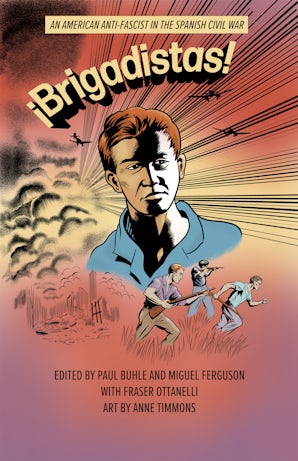

¡Brigadistas!

by Miguel Ferguson and Fraser M. Ottanelli

Illustrated by Anne Timmons

Foreword by Paul Buhle

Taking Care of Business

by Paul Buhle

Insurgent Images

by Mike Alewitz and Paul Buhle

Foreword by Martin Sheen

Article by Paul Buhle

- Insectopolis and the Fantastic Peter Kuper

- Hubert Harrison: A Giant Remembered

- The Long Road of Tariq Ali

- Empire and Popular Arts: A Note on Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz's "Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States"

- Ancient Marxist History

- Palestine, Oh, Palestine!

- The Left and the Class Struggle

- Two Intellectual Giants of the American Left

- The Struggle for Scotland's Future