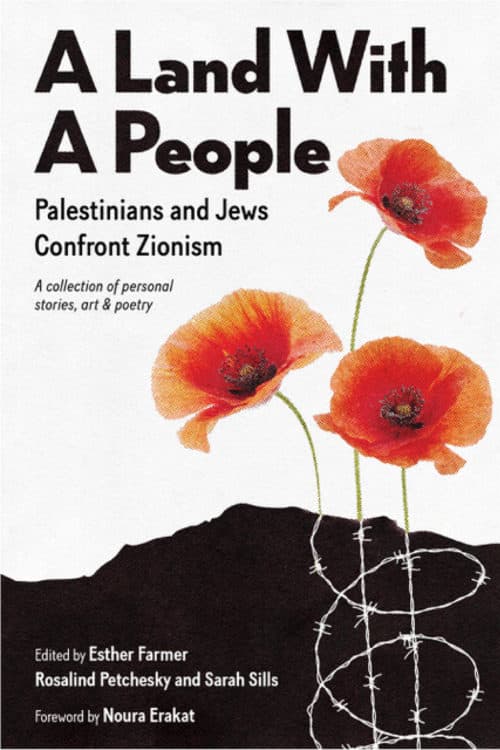

A Land With A People:

Palestinians and Jews Confront Zionism

Edited by Esther Farmer, Rosalind Petchesky and Sarah Sills

226 pages, 19$, 978-1-58367-929-6

Reviewed by Martin Halpern

The volume under review is a follow-up to an earlier Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) book, Confronting Zionism: A Collection of Personal Stories (2017). Following the publication of the latter work, JVP began performing a theater piece, ‘Wrestling with Zionism.’ When Palestinian friends asked to participate in the story-telling, JVP welcomed them. What resulted as the Jewish and Palestinian participants performed together were conversations that built “empathy and community.” Esther Farmer calls A Land With A People “a project of solidarity.” (13) Although individual readers cannot converse directly with the authors, they can gain insight into emotionally gripping personal experiences while they learn of the Nakba (the catastrophic Israeli dispossession of Palestinians that began in 1948 and continues today).

The title of the work is a critique of the Zionist concept that “Israel was a land without people for a people without land.” Zionists viewed the millions of Palestinians – Muslims, Christians, and even Jews — as less worthy than European Jews. When I first began teaching U.S. history in 1990, the textbook that I used and then replaced similarly viewed the indigenous people of the “empty” Americas as inferior and invisible. The resulting settler colonial states, from the sixteenth century to the twenty first century, were built on racism, patriarchy, exploitation, and genocide.

We learn of Palestinians suffering from losing their homes and land, from harassment and arrests, from massacres, bombings, and murders, from being banned from using the streets of their community of Hebron, from the loss of drinkable water in Gaza. Some Palestinian stories conclude on a hopeless note, but most emphasize a commitment to resist, to hold on to their identity, to return to the homeland. Riham Barghouti, a Palestinian American, describes what happened when she, her mother and sister sought to enter Palestine for a visit. An Israeli soldier discovered in their belongings a necklace containing a charm with a map of historic Palestine. Barghouti’s mother refused the soldier’s demand to get rid of the necklace. “Why was the map such a major transgression? . . . if Palestinians generation after generation, were going to remember their past and demand recognition of their identity – how could Israel go about its business of denying the existence of Palestine?” (68)

There are stories of Jews from Israel, the United States, and elsewhere. There are accounts of Jews gradually freeing themselves from Zionist ideology and from being enveloped in the closed world that Zionism offered them. There are also accounts of a change in viewpoint that comes in a “snap,” as Shirly Bahar describes her experience as a ten-year-old in an Israeli bible study class hearing her teacher critique the Israeli occupation during the First Intifada. (87)

In addition to the compelling stories, poems, and art works, A Land With A People includes a comprehensive historical essay by Rosalind Petchesky, “Zionism’s Twilight: Colonial Dreams, Racism Nightmares, Liberated Futures,” brief timelines highlighting events in the history of Zionism and of resistance to Zionism, a glossary, biographies of the authors, a bibliography, and a JVP statement on Zionism.

Zionists falsely claim that those who see Israel as an apartheid state and support the Boycott Divestment Sanctions (BDS) movement are anti-Semitic. A strength of Petchesky’s essay is to explain that Zionism’s attempt to “homogenize Jews as a single national or racial identity inextricably bound to the State of Israel is itself a form of antisemitism with very old roots.” Rather than being a unified “race” or nation Jewish people have for centuries lived in “diverse cultures, languages, racial identities, and geographies across the globe.” (20) Privileging European Jews, the Zionist state has discriminated against Jews from North and East Africa and the Middle East while inflicting apartheid segregation on Palestinians.

Although Israel has increased its territorial expansionism, its illegal settlements, and its expulsions of Palestinians, resistance continues. New organizations have developed to struggle against racism and against settlements, to defend children, political prisoners, and sexual and gender diversity. Petchesky quotes the Palestinian grass roots organizer Bassem Timini’s simple pronouncement, “We continue!” (150)

The leading role of women in the struggle against Zionism is evident throughout the volume. Some of the remembrances recount how the author’s feminism developed alongside their anti-racism and anti-Zionism. The poet Naomi Shihab Nye writes (171):

Here by the hills where angels once appeared,

my mother heard of a journalist who answered

How to solve this dilemma?

by saying, Put everything in the hands of women!

Women in black, women in white.

The men had their chance and failed

. . . . .

It is our turn now.

The debate between advocates of a two-state solution and a one-state solution is not mentioned in the text. Those who speak of their hopes for an eventual victory for justice speak not of states but of a single integrated society based on equality. How do we get there? The text notes the role of U.S. imperialism and the imperialism of other capitalist powers in promoting Israel’s domination of Palestinians. The leadership role of Palestinians, first, and secondarily, of Jews, in the anti-Zionist struggle is evident in this volume. However, it will take a broad anti-imperialist movement supported by the working class of the capitalist countries if Zionism is to be defeated. South African apartheid was defeated by just such a movement. Thus the importance of promoting and expanding the BDS movement.

You can find this review at Marxism-Leninism Today

Comments are closed.