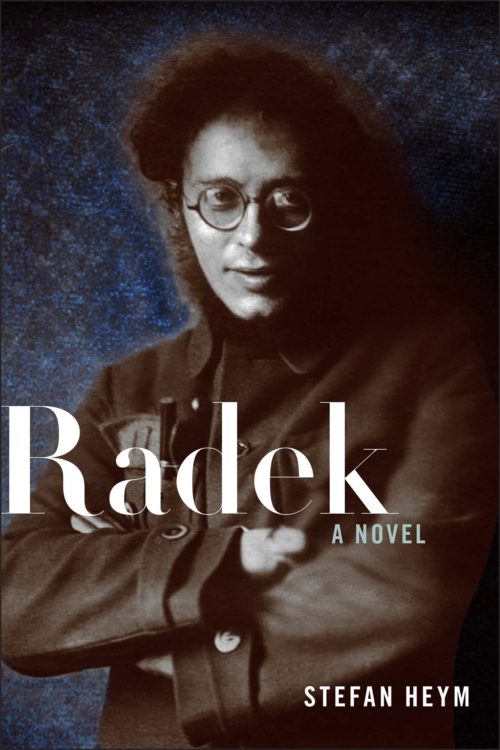

Radek: A Novel

By Stefan Heym

$28 paper / 576 pages / 978-1-58367-955-5

Reviewed by Inez Hedges for Socialism and Democracy

What goes on inside the mind of a revolutionary? This is the mental landscape that Stefan Heym draws for us in his epic novel Radek, first published in 1995 and newly translated by Alexander Locascio for Monthly Review Press. The protagonist of the story was born in 1885 Karol (“Lolek”) Sobelsohn in Lemberg (now Lviv in Ukraine) to a Lithuanian Jewish family, became a left-wing journalist who participated in the 1905 Warsaw uprising, and took the name Radek, one of many aliases. As he shuttled between Germany, Switzerland and Russia, working for various newspapers, his acerbic wit and sparkling communiqués earned him the notice of the major revolutionaries of his time: Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in Germany, Lenin, Trotsky, and later Stalin in Russia. A tireless and resourceful traveler and writer, he seemed to pop up everywhere—at the 1912 Convention of the Social Democratic Party of Germany; at the Zimmerwald conference in Switzerland in 1915 where he sided with Lenin against the ongoing war; in the sealed train that transported Lenin across Germany in 1917 after the abdication of the Russian tsar; at the failed Spartacist uprising of 1919 in Germany, where he subsequently spent time in prison. His last public appearance was as a defendant in the Stalinist trials of 1937, after which he was sent to a penal colony in Siberia where he came to a violent end.

Stefan Heym’s approach to this enigmatic and colorful character is to adopt a double-voiced mode in which much of the action is told not from the position of an omniscient narrator, but often from the inside of Radek’s (and other characters’) thoughts and perceptions in combination with a narrator who acts as an arranger without claiming to know the outcome. At first, readers might find this disconcerting. The novel’s very first line (The eternal Polish Jew) is presented as a phrase overheard by Radek as he is barred from entering the 1912 Convention. We enter into his musings: “No, he had not misheard, even if we had only stood in the entrance doorway to the hall, since they hadn’t let him into the hall itself: not you, Comrade Radek, the marshal grinned, not you” (33). This skillfully deployed narrative technique allows much of the action to be presented from inside Radek’s perception of it, though not as stream-of-consciousness—the narrator is also there, commenting alongside Radek. Early on, Radek compares himself to the character of Danton from Georg Büchner’s 1835 play Danton’s Death about the French Revolution (“They wouldn’t dare, he thought—but Büchner’s Danton has said that…and it had ended with the guillotine for Danton,” 39); in tandem, the narrator prefaces each of the novel’s eight sections with quotations from Büchner’s play.

This technique works brilliantly to create suspense and dramatic interest in that the reader is asked to see the world through the eyes of its main protagonist. We don’t get inside the thoughts of Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, or even Rosa Luxemburg in the same way—this is the journey of a single soul who sails through the shoals of revolution, trying to maintain a true course while also surviving. We might get an insight into Lenin, but only through the filter of Radek: “Of course, he recognized Lenin’s strategic superiority without envy, his far-reaching vision…nevertheless, if only to cultivate his own self-confidence, it tempted him to disagree at least here and there before accepting whatever particular dictum of Lenin’s; and Lenin, even though he appreciated his man’s talents for press, propaganda and occasional dirty work, was annoyed by the implied irreverence every time they had to deal with each other (196).”

Radek had something of the trickster about him which allowed him to prevail where others failed. Denied entry into Germany after the 1918 armistice, at the crucial moment when the German Left was organizing the Spartacist uprising by German workers, Radek disguised himself as an Austrian prisoner of war on his way home with the right of transit through Germany, leaving his other traveling companions behind (262). Arrested in Germany after the murders of fellow revolutionaries Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in January 1919, he escaped a similar fate by passing himself off as an ambassador from Soviet Russia (306). This worked so well that, although imprisoned, he began to receive the visits of important personages and was eventually released to the opulent residence of Baron Eugen von Reibnitz where he continued to hold court (335). After returning to Russia, he and Larissa Reissner (who was married to Feodor Raskolnikov) traveled under false identities (“Nathan Fischbein and wife from Lodz”) to spark the uprising of German workers at Chemnitz, a move that was intended to spread the socialist revolution to Germany and the world. Here Radek’s envisioning of the scene at the train station is priceless, as he tries to imagine what effect his departure with the beautiful Larissa will have on his wife and daughter and the gossiping that will break out among the other passengers (377-8). In the end, the 1923 Chemnitz plot fails and with it, Lenin and Trotsky’s dream of world revolution. Stalin’s policy of “socialism in one country” begins.

Radek could never bring himself to adhere to that policy and began to openly criticize Stalin. In consequence he was removed from the Comintern (the Communist International) and moved in 1925 to the sidelines as Provost of Moscow’s Sun Yat-Sen University, which was set up to establish relations with China. His role there enabled him to criticize Stalin’s alliance with the nationalist Chiang Kai Shek. In 1927 Radek was removed from his university position and exiled to Siberia. Though he officially capitulated to Stalin in 1929, Heym suggests that this was only a ruse.

The author now brings us inside the mind of his complex hero to help the reader understand how Radek runs afoul of Stalin and is finally caught in the inextricable web of deceit and conspiracy that brings about his downfall. In his 1934 article “The Great Architect,” an article published in Pravda, Radek begins to openly criticize Stalin while seeming, on the surface, to praise him. Heym reveals his hero’s true intent: “No, they didn’t get it, they were, all of them, for years already adapted to the language of the bootlickers, and so weaned from any lateral thinking that they took his work from A to Z for a serious historical evaluation and simply did not understand the ambiguity of the matter, the intricate no, which he had hid in the acclaiming yes, the dialectic of the whole.”(533)

In is in this spirit, Heym suggests, that Radek’s “confession” at his 1937 trial should be understood. Moving again into the thoughts of his protagonist, Heym has him evaluating the tenuousness of the fabricated confession that he is asked to sign: “The confession that Luzhkin demanded of him was a too clumsily arranged story. Following the written and oral instructions of the arch-heretic Trotsky….he, Radek…intended to help bring about the defeat of socialism in the war against the Soviet Union…in close cooperation with the Nazi-German and Japanese general staffs, and, as a reward, obtain power in the country from the victorious enemy, which power they would then use…to reintroduce capitalism in Russia…” (570). Instead, Radek insists on writing his own confession, in the belief that “anyone who could even think halfway had to understand that he, Karl Radek, had undertaken to reveal to the world by contrasting his confessions with the statements of the other defendants, extorted by torture or otherwise, and by his duet with the prosecutor: the utter absurdity of it all. This was the most perfect sabotage, because it was pure dialectics (588).” In the end, he manages to squeak by with a 10-year sentence to Siberia, where, however, he ultimately perishes.

Radek’s perturbing backward look in 1995 into the history and travails of socialism—five years after German reunification—is no accident. The German-born Heym (Helmut Flieg) had fought alongside the Allies in WWII and became an American citizen before deciding to move to the German Democratic Republic in 1953. Though a committed socialist, he became a dissident in the GDR. As Victor Grossman mentions in his excellent introduction to the novel, Heym in 1990 signed the collective statement “Für unser Land” (For Our Country), arguing that aspects of socialism should be retained in East Germany even after the wall came down. In the character of Radek, Heym finds a hero with a mission, one willing to pay the ultimate price for his commitment to a socialist future, but also one who has to ask himself in the end whether one can defeat power with cleverness and cunning (588).

Translating this long novel was no doubt an enormous task which has been accomplished with felicity…..

You can read the full review with a subscription to Taylor and Francis

Comments are closed.