“Vietnam at the Movies“

Counterpunch

by Jerry Lembcke

“…..’Going back’…. implies there is something unsettling in the present that lurks in the past. Jane Fonda captured that sentiment in Sir! No Sir! with her rhetorical explanation for why the film’s look-back on G.I. resistance had been necessary. ‘Why do we go back?’ she asked sardonically, ‘because they go back,’ the pro-war hawks and military establishment. The ‘patriarchy,’ as she put it, ruminates the defeat in Vietnam like a bad sandwich growling in its stomach through a night that will not end.

The defeat in Vietnam struck at a pillar of American manhood. Vietnam veterans would sometimes be chided by older veterans: they had won their war; Vietnam veterans had lost—what kind of men were they? And the fact that thousands of veterans had joined the campaign to end the war was an indictment of their loyalty, character, and masculinity. Critics of the antiwar movement held it responsible for erosion of American military morale and the emasculation of its warriors. Slogans like “Girls Say Yes to Boys Who Say Know” sapped men’s will-to-war, they said.

The stage show FTA reached into the ranks of service members still in uniform, inspiring dissent in large and appreciative audiences wherever it went. When the war was over, it receded in American memory. But the phantasmagoria of veterans rejected, and POWs forsaken, remained lodged in the national psyche. Those mythologies displaced the realities, discomforting for militarists, that the war was lost when the troops turned against it, and the POWs truly forgotten are those whom, for reason of conscience, spoke out for peace even before their release and return from Hanoi.

The image of POWs left locked in bamboo cages—emblazoned on the POW-MIA flags that still fly on government buildings—was a powerful force in postwar revisionism. Government propaganda and popular culture cast them as hardcore heroes who had endured torture claims, and news reports that as many as 30 percent of the POWs had spoken out against the war while still held in Hanoi, were both dismissed as communist lies. Upon their release and return from Hanoi, the dissident POWs who maintained their conscientious rejection of the war were slandered as communist “dupes” who had succumbed to the stress and trauma of captivity—the anti-heroes in postwar mythology.

The war in Vietnam left a pool of angst and resentment, the kind of repressed emotion that quietly seethes until its hurts are avenged. The 2020-21 flurry of Vietnam-themed films tapped that reservoir for its market value. Doing so might have vented some anger; or it may have stirred some feelings better left dormant.

Your thoughts, my friend?”

Read the full article at Counterpunch

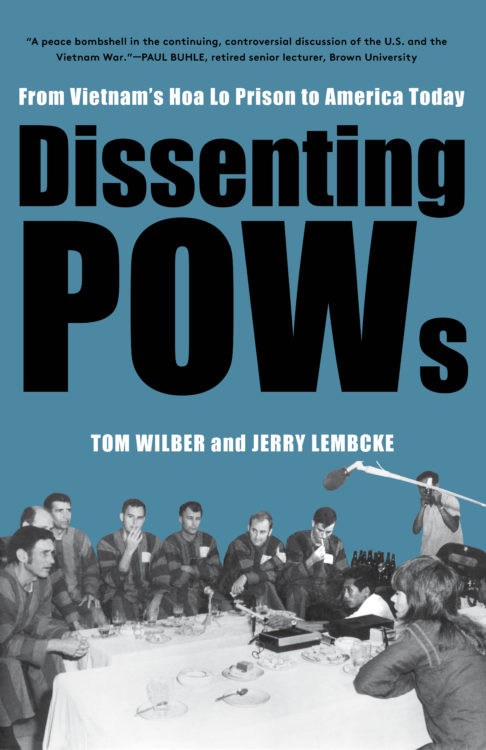

Jerry Lembcke is coauthor, with Tom Wilber, of Dissenting POWs: From Vietnam’s Hoa Lo Prison to America Today, available April 23rd.

50 years ago on April 23rd, 1971, 1000 veterans arrived in D.C. and gathered at the fence surrounding the Capitol building. One by one, nearly all of them threw their awards—their medals, ribbons, commendations, and dogtags—in disgust and outrage at the way they were used in an imperialist war of aggression against Vietnam.

On this day, Monthly Review Press is releasing Dissenting POWs: From Vietnam’s Hoa Lo Prison to America Today. In honor of the dissident POWs who took a stand against the war, but were erased from history, pick up your copy today. You can order by clicking on the front cover image below.

Comments are closed.