Also in this issue

- Twenty-First-Century Land Grabs: Accumulation by Agricultural Dispossession

- Britain's Noxious History of Imperial Warfare

- Cambodian Political History: The Case of Pen Sovann

- It's the System Stupid: Structural Crises and the Need for Alternatives to Capitalism

- Zionism, Imperialism, and Socialism

- Radical Internationalist Woman

Books by Joseph J. Varga

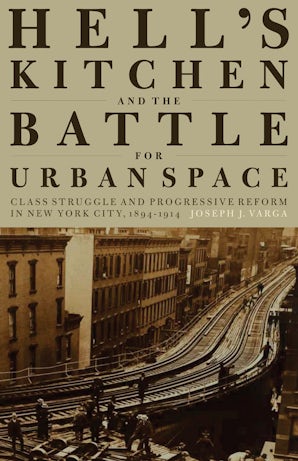

Hell's Kitchen and the Battle for Urban Space

by Joseph J. Varga