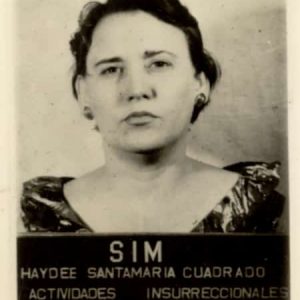

In the early 1950s, Haydée Santamaría Cuadrado moved from a rural Cuban sugar plantation to Havana, to live with her younger brother Abel. Together, they would help to establish a revolutionary movement that would change the history of their country. Haydée, as she is known throughout Cuba—Yeyé to her friends—was one of only two women among 160 men who took part in attacks on Batista’s army barracks at Moncada and Bayamo on July 26, 1953, which sparked the Cuban Revolution. In a now legendary speech during the trial for his part in these attacks, Fidel Castro paid homage to the two women who had fought alongside him:

Frustrated by the valor of the men, they tried to break the spirit of our women. With a bleeding eye in their hands, a sergeant and several other men went to the cell where our comrades Melba Hernández and Haydée Santamaría were held. Addressing the latter, and showing her the eye, they said: “This eye belonged to your brother. If you will not tell us what he refused to say, we will tear out the other.” She, who loved her valiant brother above all things, replied full of dignity: “If you tore out an eye and he did not speak, much less will I.” Later they came back and burned their arms with lit cigarettes until at last, filled with spite, they told the young Haydée Santamaría: “You no longer have a fiancé because we have killed him too.” But still imperturbable, she answered: “He is not dead, because to die for one’s country is to live forever.” Never had the heroism and the dignity of Cuban womanhood reached such heights.1

Sentenced to seven months in prison for her role in the attacks, Haydée was later charged with deciphering and disseminating Fidel’s defence speech under the title “History Will Absolve Me.” Using the nom de guerre of María, she played a vital part in the urban underground, helping to coordinate an uprising intended to distract the authorities from the arrival of eighty-two insurgents aboard a small motor cruiser, which marked the next phase of the revolutionary war. Always reluctant to leave Cuba, she went wherever Fidel needed her, travelling to Miami to secure weapons from gangsters and returning to Cuba with bullets sewn into the folds of her skirt.

Having lost the love of her life at Moncada, Haydée married a young lawyer and fellow July 26 Movement member, Armando Hart Dávalos, who would become the first post-revolutionary minister of education, and later of culture. Together they had two children and adopted many more, mainly young people displaced from their homes throughout Latin America. Beyond her extended parenting, Haydée’s greatest creation was an institution conceived to bypass the ideological blockade that descended on the island—the cultural house, Casa de las Américas. This quickly became—and remains—a nexus for intellectuals visiting the revolutionary heartland from the Americas and beyond, a place where experimentation is encouraged and solidarities are formed. Becoming a member of the Central Committee of the governing Cuban Communist Party in 1965, Haydée used her revolutionary prestige to nurture and protect many artists and writers within the house, especially when policy took a dark turn in the first half of the 1970s. In this place, which still thrives in her image, creative intellectuals from around the world come together to play a part in the island’s ever-evolving social processes. A book of letters to Haydée, published in Havana in 2010, gives an idea of the respect she commanded from many of the continent’s leading political and cultural figures, from Che Guevara to Eduardo Galeano, Gabriel García Márquez to Nicolás Guillén.

In her recent book, poet and scholar Margaret Randall, who lived in Cuba in the 1970s and became friends with Haydée, has captured the essence of this exemplary woman. In what she calls an “impressionist portrait,” Randall vividly conveys the empathy, intensity, and spiritual purity of an outwardly unassuming woman, taking us through Haydée’s early years, from the uncertain moment of her birth (the precise date of which is still debated) to her truncated education. We learn that, after her move to Havana, Haydée would prepare food for the incipient insurgents before joining them at the table to discuss strategy, and we are made privy to her eleventh-hour uncertainty about whether she and Melba Hernández would be invited to join the men at Moncada.

Through Haydée’s own words, we learn of her brother Abel’s conviction that he would not survive the attacks, and his insistence that Haydée continue the struggle, preparing her for what came next, which he knew would be a harder path. We hear how she vowed to continue living until the next milestone had been reached—long enough to discover whether Fidel was still alive, so that she could tell him that Abel loved him and had given his life for him; long enough to see the trial through, so that she could tell the world how Abel had died; long enough to survive prison, so that she could play her part in spreading the revolutionary word while her compañeros languished behind bars; and long enough to see the triumph of the revolution, honing her unique intuition for evading capture and death. Fascinating archival images are reproduced throughout the book, many of them donated by Casa de las Américas, offering a glimpse of the tenderness and solidarity that imbued the movement.

In brisk, gripping prose, Randall makes clear the challenges faced by a woman forging a new society in the second half of the twentieth century. While Western women struggled to achieve parity of education and control over their reproductive rights, the options available to young Cuban women were even more limited—confined to work as playgirls, prostitutes, housewives, or maids. “One thing no Cuban woman, of any social class or culture, was supposed to do in prerevolutionary Cuba,” Randall writes, “was take part in armed political struggle” (39). Randall also evokes the internationalism that underwrote Haydée’s cultural work, her understanding of “art as the highest form of human expression and a necessary component of social change” (23). Haydée embodied the new human subject that the revolution sought to encourage as a precursor to new social relations. At the same time, Randall notes, her life represented the contradictions that exist between and within individuals and political processes, observing that “some dreams of social change…never came quickly or permanently enough for her vision of immediate justice” (12).

With a poet’s sensibility, Randall delves into Haydée’s psyche, itemizing the values of justice and loyalty that guided her life. She shares the lighter side of Haydée’s character as a noted practical joker, and unflinchingly examines the shadow of suicide that still lingers over Haydée’s memory, exposing a family riven by untimely deaths and beset with depression. According to poet Roberto Fernández Retamar, Haydée’s successor at Casa de las Américas, “her pain grew too much for her (the eternal pain her horrible executioners [sic] caused her after the Moncada attack), her mind grew darkened, and she took her own life.”2 In her first public lecture on the subject of Moncada, delivered in July 1967, Haydée observed that it was much more difficult to speak about the events that had taken place—which she likened to the birth of her son, Abel, in their combination of agony and promise—than it was to have lived them. Through Randall’s observations, we feel her pain at being called on to recall her most terrible memories, which became more acute with every retelling.

Randall continues to probe the circumstances that led this revolutionary woman to shoot herself in the home she shared with her children, within a revolution that denounced suicide. A succession of tragedies compounded Haydée’s darker thoughts: the torture and murder of her brother, fiancé, and comrades at Moncada; the execution of her soulmate Che Guevara; the loss of her dear friend and ally Celia Sánchez to cancer; the car accident that left her in permanent physical pain; the inexplicable exodus of her husband. “She was surrounded by ghosts,” Randall writes. “Perhaps their call had become too insistent. She also trusted the revolution and must have known that she had bequeathed the tools of social change to her colleagues, family, and friends” (188). Randall posthumously diagnoses Haydée as suffering from post-traumatic stress, exacerbated by underlying familial depression. The sense emerges that Haydée understood both the value and the fragility of life, and the impossibility of leaving a vital task undone, leading us to conclude that she ultimately decided—if rational thought was possible by then—that her life’s purpose had been accomplished. “Haydée was always absolutely sure of what she needed and wanted. Once her mind was made up, there was no deterring or seducing her to an alternative decision” (191). This is a deeply personal book about a heroic woman, written by someone justifiably proud to call Haydée Santamaría a friend.

Notes

- ↩Fidel Castro Ruz, “History Will Absolve Me,” in Castro and Régis Debray, eds., On Trial (London: Lorrimer, 1968 ), 9–108; also available at http://marxists.org.

- ↩Roberto Fernández Retamar, “Sobre la Revista Casa de las Américas,” paper presented at the Meeting of Caribbean Magazines conference, Casa de las Américas, Havana, November 19, 2009.

Comments are closed.