…once the earthly family is discovered to be the secret of the holy family, the former must then itself be criticized in theory and revolutionized in practice.

We should strive for the same clarity on the complex woman question that we insist upon when dealing with the complex Negro question, and for the same reason.

The Question

Women?

Yes.

In the late 1960s, the North American women’s liberation movement was reaching a highpoint of activity, its militancy complemented by a flourishing literature. This was the environment into which Margaret Benston’s 1969 Monthly Review essay, “The Political Economy of Women’s Liberation,” struck like a lightning bolt.4 At the time, many in the movement were describing women’s situation in terms of sociological roles, functions, and structures—reproduction, socialization, psychology, sexuality, and the like. In contrast, Benston proposed an analysis in Marxist terms of women’s unpaid labor in the family household. In this way, she definitively shifted the framework for discussion of women’s oppression onto the terrain of Marxist political economy.

Benston’s Argument

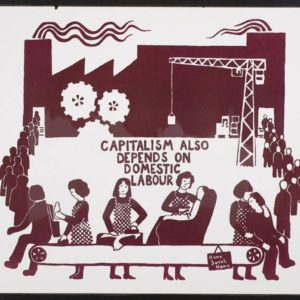

Benston started with the problem of specifying the root of women’s secondary status in capitalist society. This root is “economic” or “material,” she said, and can be located in women’s unpaid domestic labor. Women undertake a great deal of economic activity—they cook meals, sew buttons on garments, do laundry, care for children, and so forth—but the products that result from their work are consumed directly without ever reaching the marketplace. In Marxist terms, these products have use value, but they are not commodities because they lack exchange value. For Benston, women constitute the “group of people who are responsible for the production of simple use-values in those activities associated with the home and family.” Hence, the family is an economic unit whose primary function is not consumption, as was generally held at the time, but production. “The family should be seen primarily as a production unit for housework and child rearing.”

Moreover, Benston maintained, women’s unpaid domestic labor is technologically primitive and outside the money economy. Each family household therefore represents an essentially preindustrial and precapitalist entity. Although women also participate in wage labor, such involvement is transient and not central to women’s definition as a group. It is women’s responsibility for domestic work that provides the basis for their secondary status and enables the capitalist economy to treat them as a massive reserve army of labor. Equal access to jobs outside the home will remain a woefully insufficient precondition for women’s liberation if domestic labor continues to be private and technologically backward.

The article’s strategic suggestions centered on the need to create a precondition for women’s liberation by converting work now done in the home into public production. That is, society must socialize housework and child care. “When such work is moved into the public sector, then the material basis for discrimination against women will be gone.” Benston thus revived a traditional socialist theme, not as cliché but as forceful argument made in the context of a developing debate within the contemporary women’s movement.

Benston’s discussion had a certain simplicity that even at the time invited criticism. Its facile dismissal of women’s labor force participation required correction, as did its delineation of their domestic labor as a remnant from precapitalist modes of production that had somehow survived into the capitalist present. Also missing was any consideration of differences by race, class, or sexuality, all then-pressing concerns in the women’s liberation movement. Nonetheless, Benston’s essay was probably the first of a small group of pieces that established the material character of unpaid domestic labor in the family household, and pointed toward an analysis of the way it functions as the basis for the host of contradictions in women’s experience in capitalist society. These theoretical insights were to have a lasting impact on subsequent socialist-feminist work.

The Context

It is hard today to convey the atmosphere in which Benston’s article had its effect. The decade of the 1960s was a time of international upheaval, social movement, and much discussion about society and what needed to be changed. Young people who yearned to participate found the atmosphere intoxicating. Statements and analyses circulated at what seemed a rapid pace, despite the absence of such tools as personal computers, high-powered copying machines, the web, and the Internet. Typewriters, carbon paper, stencils, mimeographs, ditto machines, and the post office had to suffice. Most of us used manual typewriters, a few had access to electric ones. The marvelous IBM Selectric, with its fixed carriage and dazzling typeball, had only just been introduced.

In addition, courses reflecting the growing interest in women’s and black liberation, Marxism, revolution, radical social change, and the like were still few and far between. This meant that if one wanted to learn more about these issues, it would mostly have to be outside conventional schools and universities. So, we women’s liberationists (like other would-be activists and theorists) formed self-directed autonomous groups dedicated to linking study and activism. The story is well known, taking place in the United States against the background of a range of militant social movements.

Thus, a draft of Benston’s article was initially shared in mimeographed form under the title “What Defines Women? The Family as a Production Unit.” Once the text was published by Monthly Review, small collectives like the New England Free Press produced pamphlet versions, and it was included in several hot-off-the-press anthologies devoted to issues of women’s liberation.5 It also had an important international impact.6

A Straight Line

Benston’s work was particularly electrifying for those of us trying to think theoretically about women’s liberation and Marxism. Looking back, I see a straight line from Benston’s groundbreaking 1969 article to my own efforts in this tradition. Here was someone using Marxist concepts—use value, exchange value, commodity, labor power—to analyze the situation of women. It struck me as at once startlingly original and perfectly obvious, once one thought about it. And less than a year later, when Peggy Morton suggested incorporating the discussion within the notion that the family household is “a unit whose function is the maintenance and reproduction of labor power,” I was completely seduced.7 This was the way I wanted to go.

What was it that spoke so compellingly to me? I think I must have embraced this analytical framework because it was consistent with my own history. As a child growing up in a left-wing family—and despite claiming as an adolescent to reject its communist commitments—I had absorbed a basically materialist (in the Marxist sense) outlook and a rudimentary awareness of African-American issues, as well as of what was called male chauvinism, and of course social class. In Europe, where I lived after dropping out of college, I began to understand the potential of social movements as I saw tens of thousands of workers leave their factories to go on strike. I also met young people who had opposed and then fled oppressive regimes, saw firsthand the physical destruction of capitalist war, and encountered the hopes of anticolonial independence activists.

Back in the United States after two years abroad, I finished college and entered graduate school in art history. At the same time, I was drawn to the civil rights movement and especially to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), its most liberationist organization. I spent summers in Mississippi with SNCC in 1964 and 1965, after which I joined the women’s liberation movement. While I was deeply committed to my graduate studies, the possibility that I might be able to contribute to the knowledge developing within the women’s liberation movement seemed irresistible. I began to read, teach, and publish on U.S. women’s history and on the problem of developing a feminist perspective on art history. I also started reading Karl Marx seriously and joined a Marxist study group. Eventually, I set out on the path initiated by Benston.

For most of the 1970s, I wrestled with the conundrum of using Marxist theory to address the problem of women’s oppression. Beyond a critique, I wanted to come up with an alternative. In a series of articles and, finally, in Marxism and the Oppression of Women: Toward A Unitary Theory, published in 1983 by Rutgers University Press and Pluto Press, I offered the beginnings of a materialist analysis that put childbearing and the oppression of women at the heart of every class mode of production.8

Central to my approach was a confrontation with the Marxist tradition pertaining to the situation of women. Texts long regarded by socialists as canonical offered, I thought, only an unstable hodgepodge of fragments. I therefore undertook a lengthy critical reading of such concepts as the reproduction of labor power, individual consumption, and the industrial reserve army as they appeared in the writings of Marx, Frederick Engels, August Bebel, V. I. Lenin, Clara Zetkin, and others. Once disentangled, reworked, and supplemented, the concepts could become the starting point, I hoped, for the construction of a more adequate theoretical framework.

My work challenged then-current socialist-feminist analyses of women’s oppression in capitalist societies on at least two counts. Where socialist feminists commonly located domestic labor outside the processes of capitalist accumulation, I positioned it at its center. And where socialist feminists often assumed female subordination to be rooted solely in women’s relation to the economy, I argued that it is established by their dual situation, differentiated by class, with respect to domestic labor and equal rights. That is, capitalism stamps the subordination of women with a twofold character, political as well as economic.

I also continued my interest in history, using a Marxist-feminist lens to look at women and social movements, and at the problem later termed intersectionality. I questioned the common belief that the 1960s and ’70s U.S. women’s movement was exclusively white and middle class until the 1980s, when African-American women became involved.9 Rather than latecomers to feminism, African-American women had been active in women’s movements in recognizably feminist ways as early as the nineteenth century. And, in the mid–1960s, longtime black women activists from the labor, civil rights, and left communities were key to the formation and development of the National Organization for Women (NOW) as an “NAACP for women.” Also in the 1960s, radical black women founded independent black feminist organizations such as Poor Black Women, SNCC’s Black Women’s Liberation Committee, and the Third World Women’s Alliance. Black women on welfare likewise forged a distinctive brand of feminism, and household workers made efforts to organize on their own behalf. These various histories show that in order to “see” race and class, we must, on the one hand, do better history and, on the other, reconceptualize our notions of what feminist activism looks like.10

The term intersectionality was first inserted into feminist conversation by black legal activist Kimberlé Crenshaw in the 1980s to describe the interaction of multiple categories of social difference. In my view, it bore a family resemblance to a venerable mantra used on the left throughout the 1960s: race, class, and gender. In both cases, vectors of oppression were said to constitute comparable phenomena with similar effects operating on parallel yet somehow intertwined tracks. But it was never clear what this trilogy meant or how its components functioned, something that always bothered me. Over the years, I tried to distinguish qualitatively among race, class, and gender, as well as the other categories that were later included within the increasingly popular concept of intersectionality. Rather than comparable oppressions of equal causal weight, race, class, and gender need to be viewed, I argued, as each having its own theoretical and historical specificity.11

My advocacy of Marxist-feminist theory did not come at an auspicious moment. By the early 1980s, neither of my intended audiences was likely to pay much attention. The U.S. left, never that strong and always hostile to feminism’s supposedly inherent bourgeois tendencies, was losing ground in an increasingly conservative political climate. Meanwhile, socialist feminism had dwindled to a minor trend within a rapidly growing women’s movement that largely rejected the so-called “unhappy marriage of Marxism and feminism.”12

Thirty years after its initial appearance in 1983, Marxism and the Oppression of Women was republished in an expanded edition by Brill/Haymarket Books. To my surprise, the book seems to have found its audience in the twenty-first century. As the authors of its new introduction comment, it had survived a three-decade “below-the-radar” existence until, “amidst a resurgence of anti-capitalist struggle and a small renaissance for Marxist and radical thought, its republication seem[ed] both timely and compelling.”13 In other words, the historical context has changed. Proponents of the increasingly popular Social Reproduction Theory view the book as foundational, and a number of translations have appeared or are underway.

At its core, Marxism and the Oppression of Women offered my best effort to develop an analysis deploying rigorously defined concepts and carefully delineated units of analysis—a quest triggered originally by my reading of Benston’s article.

Who Was Margaret Benston?

Because Monthly Review identified Benston as “a member of the Chemistry Department faculty at Simon Fraser University” in Vancouver, British Columbia, I always assumed she was Canadian. Morton, who so importantly introduced the concept of reproduction of labor power into Benston’s framework, also seemed to be Canadian. What was going on in Canada, I asked myself, to produce such stunningly fresh ideas? Perhaps the Canadian left had been better able to hang on to its activist and intellectual traditions in the face of Cold War hostility than we had in the United States? Certainly, that was true of the United Kingdom, whose emerging women’s liberation literature seemed in many ways far more sophisticated than ours. But I never investigated these questions and never met Benston.

I have since learned that Benston was an extraordinary person—immensely talented and passionately dedicated to feminism and her work as a scientist. She died in 1991 at age 53, and most of what I know about her comes from a special issue of Canadian Women’s Studies/Les Cahiers de la Femme, in which friends and colleagues mourned her untimely death. “Maggie grew up in a working class family in a small logging town in the state of Washington,” wrote her identical twin sister, also a scientist.

She studied chemistry and philosophy as an undergraduate during the late 1950s, collected a Ph.D. in theoretical chemistry at the University of Washington and Berkeley and then did post-doctoral work at the University of Wisconsin during the mid 1960s. Social class, geographical location, historical period, and professional field all restricted her to a mostly apolitical attitude during this time (which did have in the background a strong distrust of wealth and privilege). In addition, these factors meant that, unlike many others of the period, she did not rebel against her background by becoming a hippie, but by becoming middle class and a scientist/scholar. Her interest in politics and the possibility of social change first appeared when she arrived at Simon Fraser University.14

A close friend and coworker at Simon Fraser recalled that

Maggie was the most intelligent person I have ever known.… She had the ability to look at issues in ways that escaped the usual paradigms and hence offered new ideas and possibilities. It was not surprising that she had a different way of tackling intellectual questions, since she had been trained as a scientist and most of the rest of us were from the humanities and social sciences. But what was surprising is that she was not locked into scientific models and myths, and could use analytical tools without having to repeat the same patterns. And she liked people. She was intrigued by and interested in all and sundry—simple enough to say but actually quite a rare quality.15

She was also fun: “What I most admired about Maggie Benston was her lack of pretense, her blissful indifference to proper roles and social demeanor. She was herself from the way she dressed and did her hair, to the way she gave a speech, to the way she played the guitar and sang in that light, wistful voice of hers. She was my kind of scientist.”16

Benston did not evolve into this person by some magical process of internal metamorphosis. She was shaped as well by her participation in what was going on at Simon Fraser University on the Canadian West Coast.

When she got to Simon Fraser, it was in political ferment and she became caught up in the intellectual excitement of socialism and feminism. She used to credit the dancing of the 60s and its freedom of movement with allowing her to hear what the radicals were saying. Freedom of the body helped to free the mind. Marxism as a framework made sense, something that for the first time offered the possibility that social forces could be understood and then changed. It was a revelation, and her life and her work began to be informed by political ideas.17

Simon Fraser, a Canadian public research university, was founded out of whole cloth in the mid–1960s.18 Journalists nicknamed it “the instant university.” And it was not just new, with sparkling buildings rising in ambitious isolation on Burnaby Mountain east of Vancouver, British Columbia, but it was also intended to be innovative. Reflecting a growing interest in interdisciplinary studies, the university started out with a set of departments that sometimes combined traditional subjects. Especially consequential for its future development was the merging of three disciplines into the Politics, Sociology, and Anthropology Department (PSA), to be headed by T. B. Bottomore, a Marxist British sociologist. The Simon Fraser faculty was mostly young, untenured, and had little teaching experience; many came from outside Canada, including some from the United States fleeing the draft. As elsewhere in the 1960s, much about the workings of the university began to be questioned. In the PSA Department, hiring, tenure, academic discipline lines, hierarchical governance, curriculum, teaching methods, grading practices, the role of teaching assistants and students, and the confidentiality of departmental records all came up for grabs. This was the setting into which Benston entered when she joined the Chemistry Department in 1966 as a member of the university’s first cohort of faculty members.

By 1968, Simon Fraser University was in turmoil as were universities throughout North America and indeed the world. The crises peaked at Simon Fraser when the PSA Department went on strike, supported by colleagues and students across the campus. Eventually, eight faculty members were let go, the department was broken up, many students lost their scholarships or left in dissatisfaction, and Simon Fraser’s administration regained control. In an article published in Monthly Review in 1970, fired PSA faculty member Kathleen Gough, a senior British anthropologist and longtime Marxist, concluded that the experience “suggests that radical, or even (truly) ‘concerned liberal’ faculty can carry on intellectual and political struggle only for brief periods. Most must probably capitulate, become teaching nomads, or seek a berth elsewhere.”19

Benston supported the faculty and students caught up in the PSA affair, but she was no doubt sheltered from its worst consequences by being in the Chemistry Department. She was also involved in the Vancouver Women’s Caucus, an independent and explicitly socialist as well as feminist organization founded in 1968 to bring together faculty, students, and community members. As she recalled in a later interview: “We viewed ourselves as connected with the left clearly, but as a separate women’s group. And the use of the word ‘caucus’…implied politics, it implied activism…even if we weren’t a caucus of anything except the human race.”20 In the 1970s, Benston was key to the formation of Simon Fraser’s Women’s Studies Program, the first to be established in Canada.

I assume Benston participated in Marxist study circles as well as socialist-feminist organizations, as we did on the East Coast. Perhaps she was also a member of a women’s study group? What texts did the members of these groups read? Who else was there? Surely, given the Canadian context, there were some who came out of the traditions of the so-called Old Left, such as Gough. Could one of them have mentioned Mary Inman’s work on the Woman Question?

I first became aware of Inman in the 1980s and always wondered if she could have inspired Benston in some way. Born in 1894, Inman was an energetic and brilliant member of the U.S. Communist Party who in the late 1930s started writing about women’s liberation. Her work, which aimed to analyze the situation of women using an exacting Marxist framework, was at first welcomed by the Party but then became the object of a fierce internal controversy. Inman soon left (or was expelled from) the Party and devoted the rest of her life to advancing her side of the argument. In 1964, just as the North American women’s liberation movement was emerging, she self-published an accessible forty-four-page booklet on the topic, The Two Forms of Production Under Capitalism. I can just see her leaving her Long Beach, California, home to travel up and down the West Coast—lecturing, meeting with small groups, and selling the booklet. Could she have gone as far as Vancouver?21

Without further research, it is impossible to determine whether Inman’s writings were known in the socialist-feminist Vancouver community. Nonetheless, rereading her main publications against Benston’s Monthly Review article, I have the impression that Benston’s thinking was on a somewhat different wavelength, although comparable in its goals. What is clear is that Inman and Benston both believed that “the Woman Question…has an economic basis in the material conditions of social production” and sought a methodologically rigorous solution along Marxist lines.22 No wonder I was attracted to their work.

A Better World

The 1960s and ’70s were a time of high hopes for the left. Constantly active with innovative plans and wise strategies, Benston seems to have been full of that optimism. As a friend remembered, up to her death Maggie “maintained her hope in the reforming possibilities of Women’s Studies.… Above all, she remained committed to the vision of a better world for women and men.”23

And always, “Maggie was adamant that we were linked to [the] community and had a responsibility to it. She rejected the opposition between political commitment and intellectual pursuits.”24 This, of course, is an eternal dilemma for intellectuals on the left, tied to the maintenance of hope. After losing her job at Simon Fraser University, for example, Gough envisioned a local Community Center for Research and Education that would be “open to the public and financed from contributions…[holding] workshops and classes which seek to explain day-to-day problems of working men and women in the context of Canada’s place in imperialist society.” This would be “a continuing effort by working intellectuals to share knowledge for collective political struggle. With the students and the secretaries, we will bring PSA off the mountain, and in our end find our beginning.”25

My own investment in hope for a better world has fluctuated. At the time I was writing Marxism and the Oppression of Women, that hope took the most abstract of forms. Using the theoretical framework I had developed, and speaking as precisely as I could, I ended the book on what was, in its own way, a hopeful note.

“Historical materialism,” I wrote, “poses the difficult question of simultaneously reducing and redistributing domestic labor in the course of transforming it into an integral component of social production in communist society.… The proper management of domestic labor and women’s work during the transition to communism is therefore a critical problem for socialist society, for only on this basis can the economic, political, and ideological conditions for women’s true liberation be established and maintained.” Which means, logically, that as a society undertakes the transition, “the [working-class] family in its particular historical form as a kin-based social unit for the reproduction of exploitable labor-power in class society will also wither away—and with it both patriarchal family-relations and the oppression of women.”26

I also pointed to the few comments that Marx and Engels made about women, men, and family in that future communist society. As sparse as their remarks were, they thrilled me fifty years ago. In the chapter of Capital on “Machinery and Modern Industry,” Marx noted that “however terrible and disgusting the dissolution, under the capitalist system, of the old family ties may appear, nevertheless, modern industry…creates a new economic foundation for a higher form of the family and of relations between the sexes.”27 But he refrained from speculating just what these future “higher forms” would look like. Socialists believed that the communist future could not be specified in advance. Even so, Engels managed to offer some inspiring hints:

What we can now conjecture about the way in which sexual relations will be ordered after the impending overthrow of capitalist production is mainly of a negative character, limited for the most part to what will disappear. But what will there be new? That will be answered when a new generation has grown up: a generation of men who never in their lives have known what it is to buy a woman’s surrender with money or any other social instrument of power; a generation of women who have never known what it is to give themselves to a man from any other considerations than real love or to refuse to give themselves to their lover from fear of the economic consequences. When these people are in the world, they will care precious little what anybody today thinks they ought to do; they will make their own practice and their corresponding public opinion about the practice of each individual—and that will be the end of it.28

Today I am still thrilled by these glimpses of a better world. Nonetheless, and sad to say, it seems to me further away than ever.

Footnotes

- * A number of friends and colleagues read drafts and made clarifying comments and suggestions for which I am deeply grateful: Beverly Willett, Barbara Ellen Smith, Leon Shiman, Susan Reverby, Martha Gimenez, Hester Eisenstein, and Sheila Delany. I dedicate this essay to Robert Weil (1940–2014)—dear friend, inspiring mentor, fighter for social justice, and all-round good person.

Notes

- ↩Karl Marx, Theses on Feuerbach, in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Selected Works in One Volume (New York: International, 1968), 29.

- ↩Mary Inman, Woman-Power (Los Angeles: Committee to Organize the Advancement of Women, 1942), 14.

- ↩Lillian Robinson, “The Question,” in Robinson on the Woman Question (Buffalo: Earth’s Daughters, 1975).

- ↩Margaret Benston, “The Political Economy of Women’s Liberation,” Monthly Review 21, no. 4 (September 1969): 13–27.

- ↩For example, Edith Hoshino Altbach, ed., From Feminism to Liberation (Cambridge, MA: Schenkman, 1971), 199–210.

- ↩Angela Miles, “Margaret Benston’s ‘Political Economy of Women’s Liberation’: International Impact,” Canadian Women’s Studies/Les Cahiers de la Femme 13, no. 2 (1993): 31–35.

- ↩Peggy Morton, “A Woman’s Work is Never Done,” Leviathan 2, no. 1 (1970): 32–37; reprinted in Altbach, From Feminism to Liberation, 211–27.

- ↩See also, Lise Vogel, Woman Questions: Essays for a Materialist Feminism (New York: Routledge, 1995/London: Pluto, 1995).

- ↩Lise Vogel, “Telling Tales: Historians of Our Own Lives,” Journal of Women’s History 2 (1991): 89–101.

- ↩For example, see Carol Giardina, “MOW to NOW: Black Feminism Resets the Chronology of the Founding of Modern Feminism,” Feminist Studies 44, no. 3 (2018): 736–65, or Premilla Nadasen, “Expanding the Boundaries of the Women’s Movement: Black Feminism and the Struggle for Welfare Rights,” Feminist Studies 28, no. 2 (2002): 271–301.

- ↩Lillian S. Robinson and Lise Vogel, “Modernism and History,” New Literary History 3, no. 1 (1971): 177–99; Lise Vogel, “Questions on the Woman Question,” Monthly Review 31, no. 2 (June 1979): 39–59; Vogel, “Telling Tales”; Lise Vogel, “Beyond Intersectionality,” Science & Society 82, no. 2 (2018): 276–87. See also Martha E. Gimenez, “Marxism and Class, Gender and Race: Rethinking the Trilogy,” Race, Gender & Class 8, no. 2 (2001): 23–33, and Martha E. Gimenez, Marx, Women, and Capitalist Social Reproduction: Marxist-Feminist Essays (Leiden: Brill, 2018).

- ↩Heidi Hartmann and Amy Bridges used the “unhappy marriage” metaphor in a mid–1970s paper circulated under the title “The Unhappy Marriage of Marxism and Feminism.” The paper was later published with Hartmann as sole author in Capital & Class 3, no. 2 (1979): 1–33, and widely reprinted.

- ↩Lise Vogel, Marxism and the Oppression of Women: Toward a Unitary Theory (Leiden: Brill, 2013/Chicago: Haymarket, 2014). Susan Ferguson and David McNally, “Capital, Labour-Power, and Gender-Relations,” introduction to Marxism and the Oppression of Women, xvii–xl, at xvii.

- ↩Marian Lowe, “To Understand the World in Order to Change It,” Canadian Women’s Studies/Les Cahiers de la Femme 13, no. 2 (1993): 6–11, at 6–7.

- ↩Andrea Lebowitz, “1975 and All That,” Canadian Women’s Studies/Les Cahiers de la Femme 13, no. 2 (1993): 29–30, at 29.

- ↩Heather Menzies, “Science Through Her Looking Glass,” Canadian Women’s Studies/Les Cahiers de la Femme 13, no. 2 (1993): 54–58, at 58.

- ↩Lowe, “To Understand the World,” 7.

- ↩My information about Simon Fraser University is drawn from the following sources: Hugh Johnston, Radical Campus: Making Simon Fraser University (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2005); Bryan D. Palmer, Canada’s 1960s: The Ironies of Identity in a Rebellious Era (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009); Kathleen Gough, “The Struggle at Simon Fraser University,” Monthly Review 22, no. 1 (May 1970): 31–45; David H. Price, Threatening Anthropology: McCarthyism and the FBI’s Surveillance of Activist Anthropologists (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004); Frances J. Wasserlein, “‘An Arrow Aimed at the Heart’: The Vancouver Women’s Caucus and the Abortion Campaign, 1969–1971” (master’s thesis, History, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada, 1990).

- ↩Gough, “The Struggle at Simon Fraser University,” 44.

- ↩Wasserlein, “‘An Arrow Aimed at the Heart,'” 56.

- ↩For Mary Inman (1894–1985), see above all Kate Weigand, Red Feminism: American Communism and the Making of Women’s Liberation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001). Inman’s main publications were: In Woman’s Defense (Los Angeles: Committee to Organize the Advancement of Women, 1940); Woman-Power; and The Two Forms of Production Under Capitalism (Long Beach: Mary Inman, 1965). Her papers are at Schlesinger Library.

- ↩Inman, The Two Forms of Production, 5.

- ↩Lebowitz, “1975 and All That,” 30.

- ↩Lebowitz, “1975 and All That,” 30.

- ↩Gough, “The Struggle at Simon Fraser University,” 45.

- ↩Vogel, Marxism and the Oppression of Women, 180–82.

- ↩Karl Marx, Capital, vol.1 (1867; repr., Moscow: Progress, 1971), 460.

- ↩Frederick Engels, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884; repr., New York: International, 1972), 145.

Comments are closed.