Also in this issue

Books by Andy Merrifield

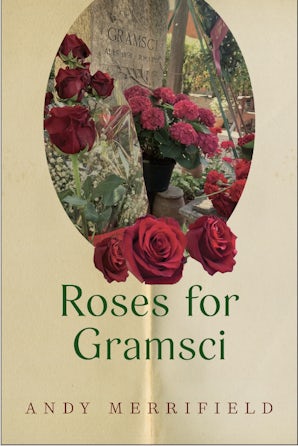

Roses for Gramsci

by Andy Merrifield

Beyond Plague Urbanism

by Andy Merrifield

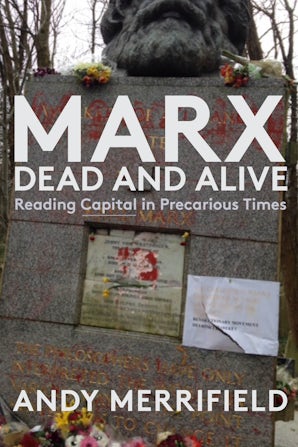

Marx, Dead and Alive

by Andy Merrifield

Dialectical Urbanism

by Andy Merrifield