“A horse, a horse!!! My kingdom for a horse!”

William Shakespeare’s play Richard III has been celebrated as one of the greatest ever written in the English language. Although it was completed by Shakespeare in 1597 during the reign of Elizabeth I, it was not performed on stage until 1633, during the reign of Charles I.1 For many years the play was regarded as mostly historically accurate, although doubts begin to form in the twentieth and, especially, in the twenty-first centuries, as two moot court, or mock trials, of King Richard III failed to convict him of killing his two nephews in his effort to take the English crown.2 Some historians began to doubt the reliance of Shakespeare and previous historians on Sir Thomas More’s book, The History of King Richard III, which portrayed Richard as a hunchback and a tyrant.3 More’s book also premiered long after his death, during a year in which one of England’s greatest influenza pandemics occurred, later causing the death of Queen Mary I.4 As I will demonstrate, the year 1557 also corresponds to one of the worst years of economic performance for England during the sixteenth century.5

Over the last ten years or so, there has been a resurgence of interest in the English king Richard III, especially after his remains were found in 2012 after being lost or missing for centuries. Prior to this, there were many publications, reports, and documentaries alluding to a “smear” campaign being conducted against the king by either the Tudor monarchs who succeeded him and/or by their confederates and surrogates. It is alleged that this was done in order to promote and make the Tudor dynasty of the sixteenth century (comprising the reigns of Henry VII, Henry VIII, Mary I, and Elizabeth I) appear to be much better leaders by comparison, and make the social and economic times of Tudor England look better than the bloody and bad times of the fifteenth century. The latter is characterized by the continuation and final ending of the Hundred Years’ War and the War of the Roses, as well as by Richard’s alleged usurpation of the crown and tyranny during his brief reign (1483–1485). Shakespeare has even been accused of being complicit in promoting the Tudor myth, though perhaps unwittingly, due to his reliance on the history being disseminated in the playwright’s time, long after the demise of Richard III.

Since fairly advanced and well-reasoned conjectures of economic activity now exist for the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, I examine the economic times of Richard III and his predecessors of the fifteenth century and compare these to those of his Tudor successors. The conjectures suggest poorer economic performance and higher taxation during the Tudor reign compared to the previous century, making one wonder if another reason for the creation of the Tudor myth is to downplay bad economic performance during their reign. It also raises the question as to whether the vilification of Richard III helped obscure the bad economy of sixteenth-century England. When examined from a long-run perspective, this poor economic performance also can be considered part of the economic discussion of the transition from feudalism to capitalism. Richard III’s demise and vilification possibly and partially can be understood in the context of this transition.

At the same time as the vilification of Richard III, there began the rise of the Tudor myth. The Tudor myth—or Tudor propaganda—that views the reign of the Tudors as one of the greatest periods of English economic performance up to that time period can, however, be seen as a great deal of hype and a history written by the “winners.”6 That is, the Tudors are elevated to heights of achievement, whereas their predecessors, especially Richard II and Richard III, are dragged through the mud. The century prior is cast as one plagued by wars, bad royal leadership of the nation, and fights over rulership. According to some, Shakespeare was a biased and partisan playwright who played fast and loose with history in order to please the elites of his time, including Elizabeth I.7

The English Economy in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries and New Estimates

From an economic point of view, the Marxian economist Maurice Dobb points out that despite increases in overall commerce, especially in agriculture and trade, the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries saw the decline of the medieval demesne system, and, as more peasants were forced into wage labor or pauperism, those who could not make the transition were thrown into often cruel and brutal workhouses started by the Tudor Poor Laws.8 Henry VIII’s confiscation of Catholic Church property and wealth was also a break with feudal times. These successes contrast with attempts by Henry VIII’s predecessors in the previous century, especially Richard III, to reform and improve government tax collection as a means of creating a stronger central government.9

Richard III was unable to accomplish “lay taxation,” or direct taxes levied on the general public to raise needed funds, as land and excise tax revenues fell and his government faced deficits.10 Richard Goddard writes that credit and finance expanded during this period in England, despite the early fifteenth century being marred by a long period of economic depression.11 Dobb, among other economists, sees this time period as a transition from a feudalistic economic system to a capitalistic one, although there is disagreement among scholars over the major cause or causes of the transition.12 These debates concern whether the “prime mover” of the transition was class struggle, expanding trade, imperialism, the growth of urban centers, or some combination of these factors. Finally, J. H. Hexter disputes claims that the Tudor period was one that benefited most royal subjects, contrary to Tudor mythology.13

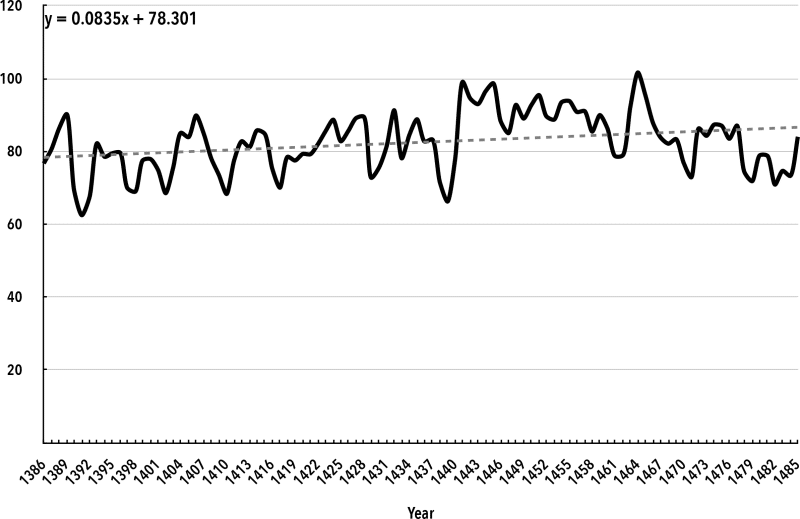

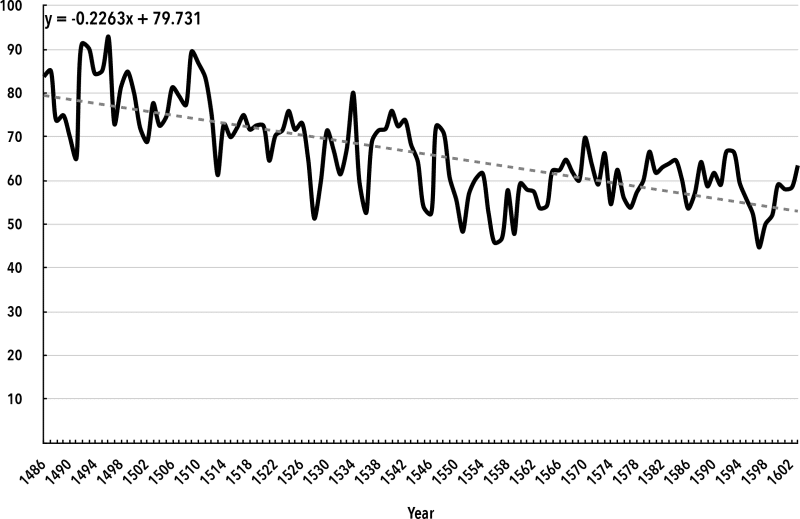

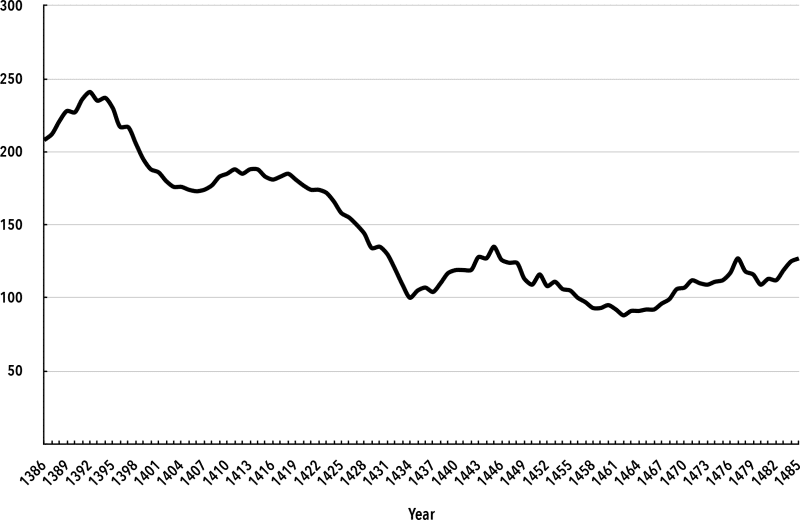

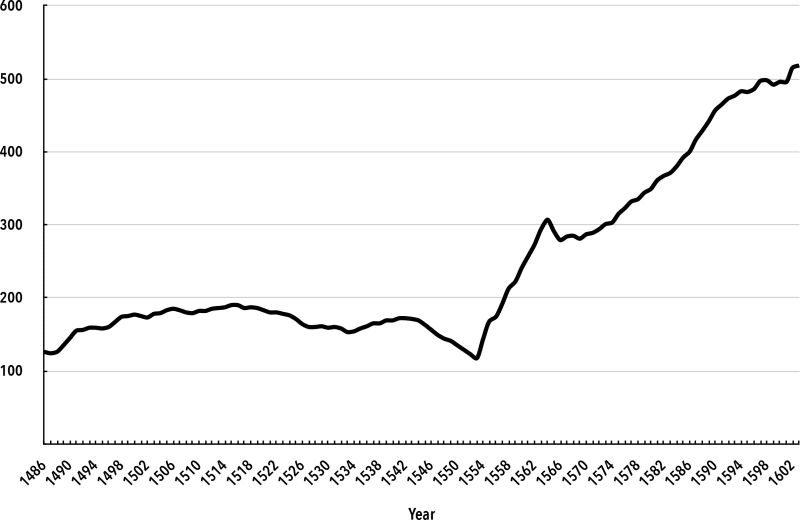

Conjectures developed shortly before or during this century by economic historians, such as Patrick K. O’Brien, Phillip A. Hunt, Gregory Clark, Stephen Broadberry, and others, may shed light on how good or bad the economy under the Tudors was when compared to Richard III and his predecessors of the late fourteenth century and most of the fifteenth century.14 Using Clark’s estimates for real (inflation adjusted) net national income (NNI) per capita for England, Chart 1 indicates that the late fourteenth century and entire fifteenth century showed little growth, averaging a rate of only £0.0835 per year. In fact, NNI per capita hovered around £80 per year during this period and was below this before and during Richard III’s brief reign, but then reached £84.04 in 1485, his final year as king. Chart 2, in contrast, shows declines in real NNI per capita under the Tudors (1485–1603), averaging –£0.2263 per year. By the end of Elizabeth I’s reign, real NNI per capita was only £63.484. This was probably due to the inflation and shortages of the Tudor period. Note that the year 1557, when More’s book was published, appears as one of the lowest points on the graph, at around £45 per capita. Data by Broadberry and colleagues for real GDP per capita show roughly similar trends, with slightly more favorable results for the Tudors. Unfortunately, these data neither estimate depreciation separately as a component of GDP (thus raising GDP estimates versus NNI, which does not contain depreciation estimates) nor give any data that could be used to estimate profits, rents, or taxes.

Chart 1. Real NNI per capita, Reigns of Edward IV, Edward V, Richard III, and Predecessors (pounds sterling)

Notes: From Gregory Clark, “The Macroeconomic Aggregates for England, 1209–2008,” Economics Working Paper 09-19, University of California, Davis, October 2009.

Chart 2. Real NNI per capita, Reign of the Tudors (pounds sterling)

Notes: Data from Clark, “The Macroeconomic Aggregates for England, 1209–2008.”

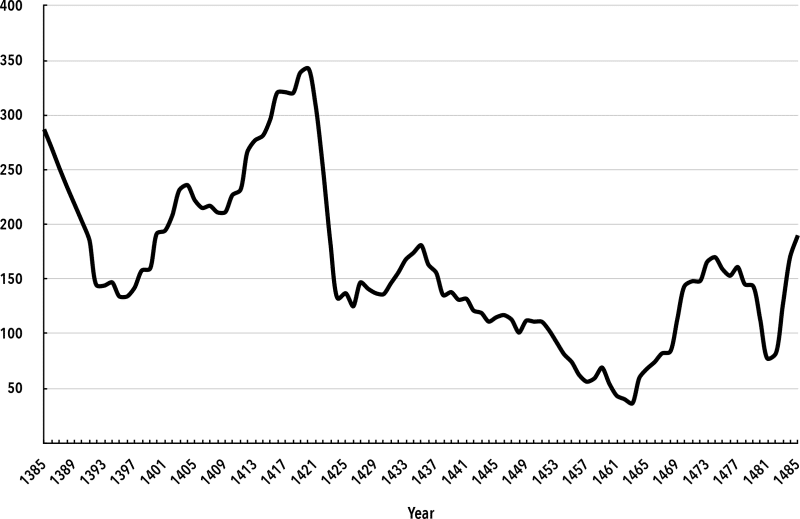

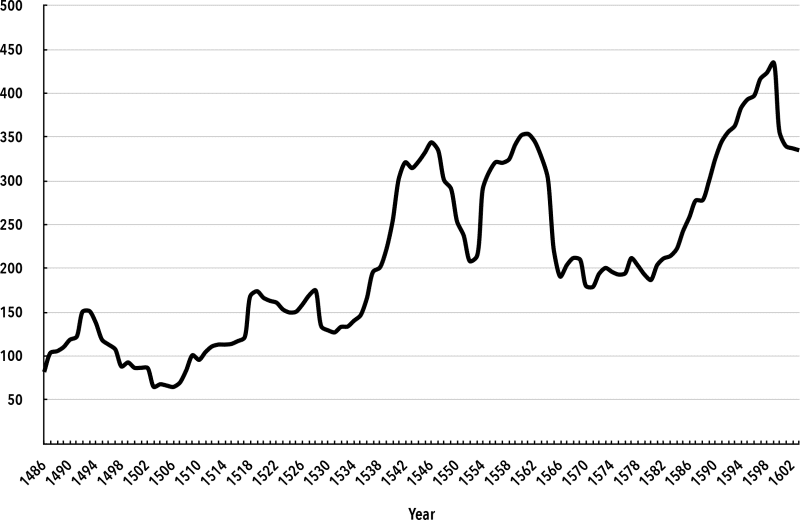

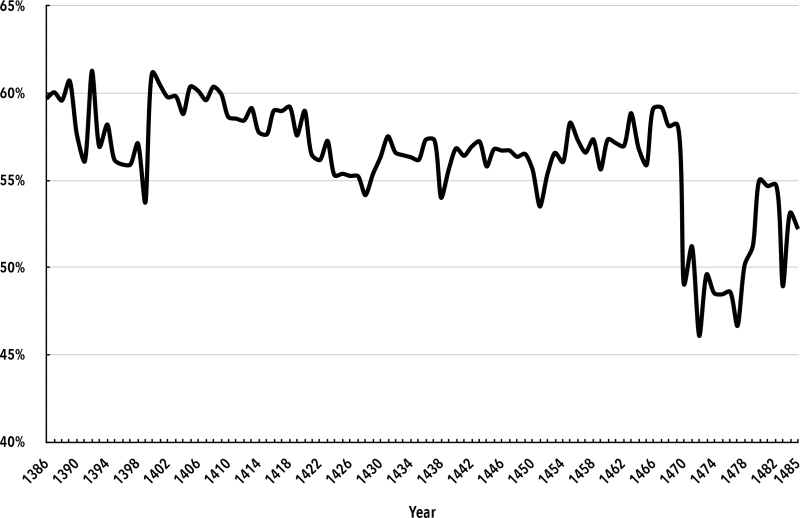

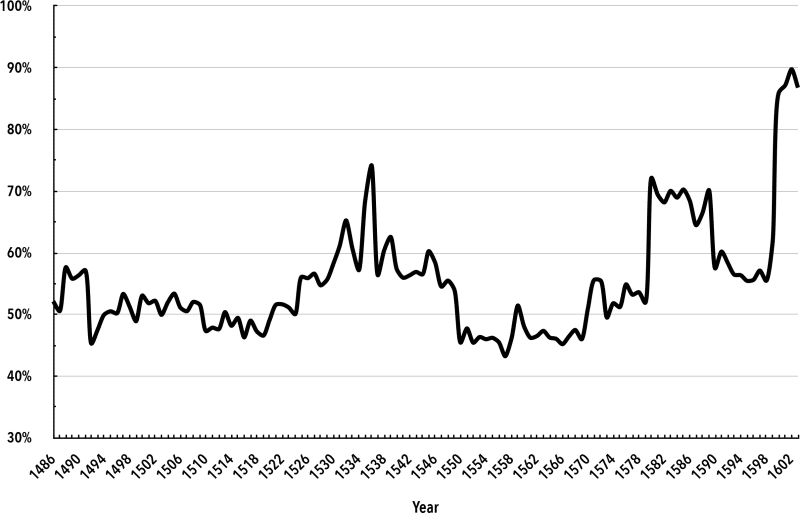

O’Brien and Hunt create an index for real direct taxes (usually taxes on income and property owners) and real indirect taxes (usually sales, excise, and renter taxes) received for England over several centuries, composed of eleven-year moving averages.15 Using their data for the two periods (the Tudor period and the pre-Tudor period, each lasting about a century), Chart 3 demonstrates the struggles faced by Richard III and his predecessors in raising revenues for the government. Tax collections rose during his term as king, but these levels are still well below the peaks reached in the early 1400s, during the Hundred Years’ War.16 However, the Tudors were more successful in extracting more taxes from the populace, as shown in Chart 4. In fact, real taxes rose dramatically during the Tudor reign, even as real NNI per capita declined. Such circumstances would not be tolerated for very long in present-day democracies, as the public would begin to feel more and more impoverished and abused by government policies. It appears that of the two centuries, the sixteenth century, economically, would be a “winter of discontent.”

Notes: Data from Patrick K. O’Brien and Philip A. Hunt, “Data Prepared on English Revenues, 1485–1815: English State Taxes and Other Revenues, 1604–48,” European State Finance Database, esfdb.org.

Notes: Data from O’Brien and Hunt, “Data Prepared on English Revenues, 1485–1815.”

Charts 5 and 6 show similar patterns for real indirect taxation levels. There was a decline in these levels from 1386 to 1485 under the monarchs who preceded the Tudors. The highest levels were mostly during the Hundred Years’ War. They did experience a slight rebound before and under Richard’s short time as king, however, beginning around 1470. For the Tudors, these taxes began to climb dramatically during the reigns of Mary I and Elizabeth I. Since real NNI per capita was declining during this time, the rise in these taxes could not have been due to economic growth, except for the dramatic increases in English exports and trade.17 Instead, this is probably a reflection of the Tudor efforts to establish a stronger and more powerful monarchy by expanding and boosting lay or direct taxation. These efforts came about as a way to limit peasant power, even if it meant diminishing the power of their lords by also taxing in-kind work done on demesnes.18

Notes: Data from O’Brien and Hunt, “Data Prepared on English Revenues, 1485–1815.”

Notes: Data from O’Brien and Hunt, “Data Prepared on English Revenues, 1485–1815.”

When it comes to the distributional shares of income during pre-Tudor and Tudor periods, Charts 7 and 8 illustrate how much the upper class of England earned in rents and profits and collected in taxes for the monarchy/government as a portion of wage income.19 The total of rents, profits, and tax revenues can be thought of as the “economic surplus” garnered by a ruling class at the expense of a working class.20 For Richard III and his predecessors, this started at around 60 percent toward the end of the fourteenth century and gradually declined throughout most of the fifteenth century. This indicates that workers had a greater share of income over time during the 1400s. Their fortunes, however, were reversed under the Tudors. In 1602, the second-to-last year of Elizabeth I’s reign, the economic surplus to wages ratio was roughly 90 percent. It was, apparently, an excellent time to own land or capital, or be part of the monarchy. This was also the time in which the enclosure movement was greatly accelerated, with peasants being removed from the land, and the imposition of Poor Laws.21

Chart 7. Economic Surplus/Wage Income under Richard III and Predecessors

Notes: Data from Clark, “The Macroeconomic Aggregates for England, 1209–2008.”

Chart 8. Economic Surplus/Wage Income under the Tudors

Notes: Data from Clark, “The Macroeconomic Aggregates for England, 1209–2008.”

The Vilification of Richard III in the Context of the Transition from Feudalism and Capitalism

As the preceding discussion demonstrates, conjectures by economic historians somewhat support the existence of a Tudor myth. In modern U.S. politics, incoming presidents have often blamed their predecessors for any and all economic misfortunes being suffered by the nation. Much of the blame for bad economic times in the 1930s and ’70s in the United States was placed on presidents Herbert Hoover and Jimmy Carter by their respective successors, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan. None of the history writings examined for this article have shown any evidence that the Tudors, their followers, or their confederates directly or indirectly encouraged attacks on their predecessors, including Richard III, based on economic reasons. In fact, if some of the historians cited in this article are correct, there really is no record of any of the Tudors explicitly mentioning or promoting the allegation of Richard III’s responsibility for the murder of the two princes, except for his successor Henry VII perhaps coaxing a false confession from someone claiming that the murders of the princes were ordered by Richard III. Others cite instances of Tudor allies explicitly stirring up negative accounts of Richard III in order to gain favor with the monarchy.22

Yet, during one of the worst years of the sixteenth century, More’s book was published, and, later, Shakespeare’s play was penned. More was an ally of Henry VIII until the author refused to support the king’s desire for a divorce. Therefore, it is possible—even plausible—that allies and supporters of the Tudors decided to create the Tudor myth to make up for the economic shortcomings of the sixteenth century, even if it meant some implicit and indirect maneuvering to ruin the reputation of their predecessors, and especially the most immediate, Richard III. More’s book and Shakespeare’s play would have helped to accomplish this. In fact, looking at a list of Shakespeare’s plays, he only wrote about English kings who preceded the Tudors. He chose not to write about any sixteenth-century monarch. This makes one wonder about possible bias on the part of the playwright. Natalie Suzelis argues that Shakespeare’s plays can be used to see the emergence of a market economy in the transition from feudalism to capitalism, and Paul Mason credits Shakespeare with seeing the downfall of feudalism and the rise of capitalism before most, since his plays mostly reflect the changes occurring in class relations and the emergence of a bourgeoisie.23

As most of the literature on the transition from feudalism to capitalism debate notes, the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries would have been major periods of change in Britain. The continued demise of the demesne/manorial system; the enclosure movement that forced peasants off land on which they had lived for generations; the English Agricultural Revolution, which lowered the number of famines and helped population levels rebound after the Black Death of the fourteenth century; and the monarchy’s desire to have more revenues (and hence more power over their subjects) all corresponded and contributed to a growing landowner and capitalist class, who saw their share of national income distribution rise during the sixteenth century. After the Black Death, most peasants and laborers saw their share of national income increase for several generations due to labor shortages. This is despite upper-class resistance to rising labor costs through restrictive labor laws, limits on wages, and increasing taxation, all of which were met with resistance and revolts by the working classes.24 However, by the time of the sixteenth century, the English population had rebounded sufficiently, and the consolidation of farms into large land holdings enabled the upper class to accelerate the enclosure movement and increase rents.

With the fortunes of the majority of people becoming worse in the sixteenth century, it is plausible that in order to help deflect criticism, some type of movement to discredit a Tudor predecessor such as Richard III commenced. The logic of such a movement would perhaps be similar to current political propaganda in modern times, along the lines of: “If you think we are bad, look at the previous bunch who were in charge!” Such political rhetoric clearly has been advanced historically. With more and more light being shed on a probable smear campaign against Richard III, any economic reasons for such an effort need to be pondered—especially due to his reign’s positioning as a pivotal point in the transition from feudalism to capitalism.

Notes

- ↩ William Shakespeare, The Tragedy of King Richard III (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001); “Dates and Sources: When Shakespeare Wrote Richard III and Where the Story Came From,” Royal Shakespeare Theatre Company, rsc.org; “Stage History: The Stage History of Richard III from the Time Shakespeare Wrote it to the Present Day,” Royal Shakespeare Theatre Company.

- ↩ “The Trial of Richard III,” documentary, ITV (Channel 3), 3:45:00, November 4, 1984, bufvc.ac.uk; “Trial of Richard III,” video archive series no. 102, 2:02:14, Media Collections Online, Indiana University, 1996, media.dlib.indiana.edu.

- ↩ Annette Carson, Richard III: The Maligned King (Charleston: History Press, 2009); Annette Carson, John Ashdown-Hill, Philippa Langley, David R. Johnson, and Wendy Johnson, Finding Richard III: The Official Account of Research by the Retrieval and Reburial Project (Havergate-Norwich: Imprimis Imprimatur, 2014); Philippa Langley and Michel Jones, The King’s Grave: The Discovery of Richard III’s Lost Burial Place and the Clues It Holds (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2014); John Ashdown-Hill, The Last Days of Richard III (London: History Press, 2010); Tim Thornton, “More on a Murder: The Deaths of the ‘Princes in the Tower,’ and Historiographical Implications for the Regimes of Henry VII and Henry VIII,” History 106, no. 369 (2021): 4–25; Phillipa Langley, The Princes in the Tower: Solving History’s Greatest Cold Case (New York: Pegasus, 2023); Thomas More and J. Rawson Lumby, More’s History of King Richard III (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1883).

- ↩ Linda Porter, The First Queen of England: The Myth of “Bloody Mary” (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2008).

- ↩ For ease of exposition, this paper uses “England” to connote England and Wales, which were joined during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

- ↩ Charles T. Wood, “Richard III and The Beginnings of Historical Fiction,” The Historian 54, no. 2 (December 1992): 305–14; Rebecca Starr Brown, “The Tudor Myth,” Rebecca Starr Brown (blog), July 4, 2017.

- ↩ Robert Brustein, The Tainted Muse: Prejudice and Presumption in Shakespeare and His Time (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009).

- ↩ In the early medieval period, the manorial demesne system was one in which unpaid serfs provided their manorial lords and barons payments for land usage and protection in the form of in-kind labor and crops grown on the manor, delivered to the lord or baron. This changed as time went on, as more serfs began to pay rent and then began to keep some of their own farm production for personal gain. Maurice Dobb, Studies in the Development of Capitalism (New York: International Publishers, 1947); R. H. Tawney, The Agrarian Problem in the Sixteenth Century (New York: Longman, Green and Co., 1912).

- ↩ Geoffrey R. Elton, The Tudor Revolution in Government: Administrative Changes in the Reign of Henry VIII (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1953); Carlo M. Cipolla, Before the Industrial Revolution: European Society and Economy 1000–1700 (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1993); Richard Bonney, “Revenues,” in Economic Systems and State Finance, Richard T. Bonney, ed. (Oxford: Clarendon, 1995); Juan Gelabert, “The Fiscal Burden,” in Economic Systems and State Finance; W. M. Ormrod, “The West European Monarchies in the Later Middle Ages,” in Economic Systems and State Finance; W. M. Ormrod, “England in the Middle Ages,” in The Rise of the Fiscal State in Europe, c. 1200–1815, Richard T. Bonney, ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999); Patrick K. O’Brien and Philip A. Hunt, “England, 1485–1815,” in The Rise of the Fiscal State in Europe, c. 1200–1815; Patrick K. O’Brien and Philip A. Hunt, “Data Prepared on English Revenues, 1485–1815: English State Taxes and Other Revenues, 1604–48,” European State Finance Database, esfdb.org; Alex Brayson, “The Fiscal Policy of Richard III of England,” Quidditas 40 (2019): 139–219.

- ↩ Brayson, “The Fiscal Policy of Richard III of England.”

- ↩ Richard Goddard, Credit and Trade in Later Medieval England, 1353–1532 (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2016).

- ↩ Dobb, Studies in the Development of Capitalism; Thomas E. Lambert, “Game of Thrones, Game of Class Struggle, or Other Games?: Revisiting the Dobb–Sweezy Debate,” World Review of Political Economy 11, no. 4 (2020): 455–75.

- ↩ H. Hexter, The Myth of the Middle Class in Tudor England (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1961).

- ↩ O’Brien and Hunt, “England, 1485–1815”; O’Brien and Hunt, “Data Prepared on English Revenues, 1485–1815”; Gregory Clark, “The Long March of History: Farm Wages, Population, and Economic Growth, England 1209–1869,” Economic History Review 60, no. 1 (2007): 97–135; Gregory Clark, “The Macroeconomic Aggregates for England, 1209–2008,” Economics Working Paper 09-19, University of California, Davis, October 2009; Gregory Clark, “The Macroeconomic Aggregates for England, 1209–2008,” Research in Economic History 27 (2010): 51–140; Stephen Broadberry, Bruce M. S. Campbell, Alexander Klein, Mark Overton, and Bas Van Leeuwen, British Economic Growth, 1270–1870 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

- ↩ O’Brien and Hunt, “England, 1485–1815.”

- ↩ It has been found that some of Richard’s problems in raising revenues were due to some English sheriffs and escheators holding back tax revenues out of their loyalty to Henry Tudor (Henry VII) so as to sabotage Richard’s ability to rule. See Sean Cunningham, “‘Fraudulently Compassed Against All Right and Conscience’: Evidence of the Defection of Richard III’s Government Officials and the Progress of Henry Tudor’s Conspiracy, 1483–1485,” The Ricardian, Journal of the Richard III Society 34, no. 1 (2024): 53–71.

- ↩ Cipolla, Before the Industrial Revolution.

- ↩ Elton, The Tudor Revolution in Government.

- ↩ Clark, “The Macroeconomic Aggregates for England, 1209–2008.”

- ↩ Paul A. Baran, The Political Economy of Growth (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1957); Paul A. Baran and Paul M. Sweezy, Monopoly Capital (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1966).

- ↩ Tawney, The Agrarian Problem in the Sixteenth Century; Ian Blanchard, “Population Change, Enclosure, and the Early Tudor Economy,” Economic History Review 23, no. 3 (1970): 427–45.

- ↩ Vanessa Hatton, “The Vilification of Richard III,” Crescat Scientia Journal of History 10 (2013): 61–83.

- ↩ Natalie Suzelis, “Shakespeare and the Transition from Feudalism to Capitalism: Ecology, Reproduction, and Commodities,” PhD thesis, Carnegie Mellon University, 2021; Paul Mason, “What Shakespeare Taught Me about Marxism,” Guardian, November 2, 2014.

- ↩ Robert Brenner, “Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-Industrial Europe,” in The Brenner Debate: Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-Industrial Europe, T. H. Aston and C. H. E. Philpin, eds. (Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 1985).

Comments are closed.