Also in this issue

Books by Torkil Lauesen

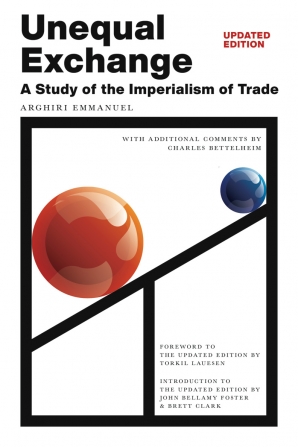

Unequal Exchange

by Arghiri Emmanuel

Notes by Charles Bettelheim

Foreword by Torkil Lauesen

Introduction by John Bellamy Foster and Brett Clark