The ongoing war between Ukraine and Russia has been driven by internal and external factors. Those factors constitute two blades of a scissors, and explaining the conflict requires taking account of both blades. The external factors center on post-Cold War U.S. geopolitical strategy and the concomitant U.S.-sponsored eastward expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). That expansion can only be understood by reference to the fractures (internal factors) created by the Soviet Union’s disintegration. The external factors reveal the role of the United States, which is implicated to the point of provoking the conflict and obstructing peace.

The external and internal factors come into play at different moments and take time to work their full effect, which is why history is so important to understanding the conflict. The two sets of factors play out over a timeline involving three key events. The first is Ukraine’s declaration of independence from the Soviet Union in August 1991. The second is the Maidan coup in February 2014 that overthrew democratically elected Ukrainian President Victor Yanukovych, who advocated Ukrainian autonomy and a nonaligned defense policy. The third is Russia’s military intervention in Ukraine, launched on February 24, 2022. This timeline is dramatically revealing. The United States and its NATO allies view the conflict as beginning in February 2022 (though sometimes saying it began when Russia first “invaded” Ukraine with the annexation of Crimea in 2014—an event following the coup), enabling them to ignore history. Russia views the conflict, more straightforwardly, as beginning with the February 2014 coup, which makes history and the onset of Civil War in Ukraine central to its political position. That fundamental difference in understanding hinders the possibility of a negotiated political settlement, and it is very hard to see how the difference can be reconciled, as accounting for history (namely the coup and the subsequent Civil War) yields a completely different narrative.

The U.S./NATO denial of history and penchant for explaining the conflict as simply an outgrowth of the February 2022 Russian “invasion,” confers a significant advantage in the accompanying propaganda war. Having the conflict begin with Russia’s military intervention is a simple, easily understood narrative. The Western public has little knowledge of or interest in history; this is especially true in the United States on the other side of the Atlantic, which is completely isolated from the conflict. Nor is Western media interested in history, which is difficult to explain and a commercial dud given a disinterested public. That configuration helps explain the resilience in the West of the U.S./NATO narrative. However, whereas denial of history works well for propaganda, it does not serve the cause of either truth or peace, as it denies the causes of the conflict which must be addressed if peace is to prevail.

Understanding the Ukraine Conflict: Internal and External Drivers

The Western U.S./NATO account of the conflict is history-light. The little bit of history that has managed to surface acknowledges, and then dismisses, NATO’s post-1990 eastward expansion. A proper historical understanding begins with the breakup of the Soviet Union. That breakup is recounted by Vladislav Zubok in his book Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union. The collapse is critical because it created the terrain for conflict.1

As noted above, the conflict can be understood via the metaphor of a scissors. One blade is the internal, conflict-prone environment created by the Soviet Union’s breakup. The other blade is the continuing intervention by the United States, including the external eastward expansion of NATO. Both blades are necessary for understanding the causes of the conflict, its gradual escalation, and its political intractability.

The Internal Blade: The Breakup of the Soviet Union

The breakup of the Soviet Union had nothing to do with democratic revolution. Instead, according to Zubok, the seeds were already sprouting by the time Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985. The center was weakening and, sensing that lessening, the leaders of the various Soviet Republics began to cultivate a resentful nationalist political discourse that claimed each had been economically exploited by the system and the other republics. That discourse gave the leadership of the Soviet Republics legitimacy and sowed the seeds of secession, which explains the domino-like collapse. Once one republic left, all were quickly willing to leave. The existing leadership of the republics became the political inheritors of power, who were then able to entrench and enrich themselves.

A version of that pattern is visible in all the former republics, but it left behind three critical fractures: nascent nationalist animosities, stranded ethnic Russian populations, and contested territories. All three were especially prominent in Ukraine and key drivers of the Ukraine-Russia conflict. Of the three, the most important is nascent nationalist animosities because they function as the pivot pin of the scissors, joining together the internal and external scissor blades of conflict.

Nationalist animosities have proven particularly acute in Ukraine, having a long historical root. Ukraine and the Don region were major battlegrounds in the Russian Civil War of 1918–1922, as captured in Mikhail Sholokhov’s epic novels And Quiet Flows the Don and The Don Flows Home to the Sea. Ukraine’s nationalist animosity was further fueled by Joseph Stalin’s collectivization of Ukrainian agriculture in the 1930s, which contributed to a famine that killed millions. Ukrainian nationalists have sought to politically exploit that famine to spur anti-Russian sentiments, claiming it was a “Holodomor” genocide targeted against Ukraine. The reality is that there is no evidence the famine was the product of an ethnically targeted campaign against Ukraine. Instead, it was a product of the combination of bad harvests and the Stalin regime’s campaign against the entirety of the Soviet Union’s peasant “kulak” class.2

In the 1930s and during the Second World War, there was a virulent underground Ukrainian fascist nationalist movement led by Stepan Bandera. Those forces fought side-by-side with Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union, and they enthusiastically participated in Ukraine’s Holocaust against its Jewish population.3 After the Second World War and into the early 1950s, they continued a low-level insurgency in Western Ukraine, aided by Britain’s MI6 secret service and, to a lesser degree, by the CIA.4

With the breakup of the Soviet Union, those fascist nationalist forces were revived and encouraged. They deepened significantly after the 2014 Maidan coup, and they have strengthened further since the 2022 Russian military intervention. Within Ukraine, Bandera is now a widely and officially celebrated figure who is especially popular in Western Ukraine. Streets are named after him, there are statues in his honor, his portrait is on a postage stamp, and he was declared a hero of the nation.5 Moreover, Bandera is celebrated by Ukraine’s military and has special standing within the Azov brigade, which is an elite and celebrated part thereof.6 That ugly reality was widely recognized in the United States and the West prior to the 2022 Russian intervention, but it has now been largely suppressed as part of the propaganda effort on behalf of Ukraine and against Russia.7

In that regard, the attitude of Israel toward Ukraine is instructive. During the conflict, Israel has shown little inclination to help Ukraine, despite both being closely allied with and supported by the United States. That restraint reflects the fact that Israel has repeatedly complained about the extensive presence of and official support for neo-Nazi activity in Ukraine. Israel’s stance is damning evidence of the ugly reality of the character of animosities within Ukraine.8

In sum, revived nationalist animosities were especially severe and especially ugly in Ukraine. For purposes of understanding the war, the important point is those animosities created deep fissures that bled both inward and outward.

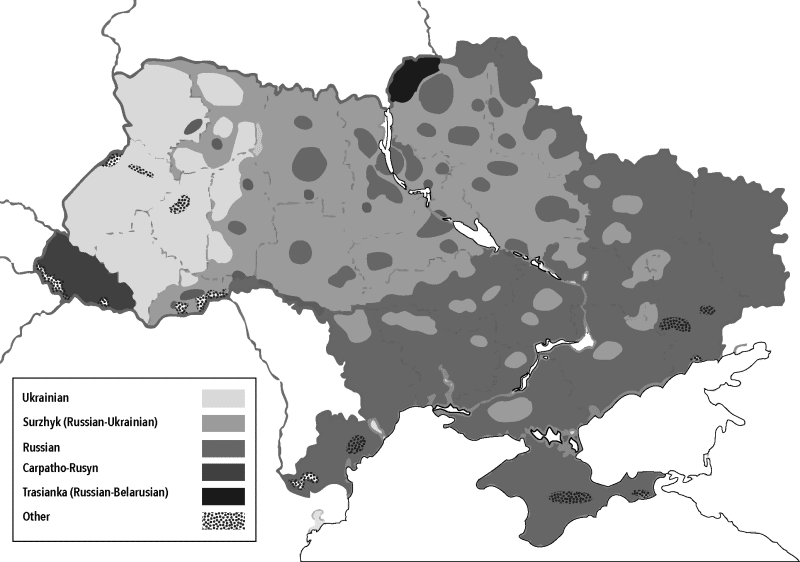

A second fracture concerned stranded ethnic Russian populations living in the former Soviet Republics. Once again, the problem was particularly acute in Ukraine, where the borders had been drawn under the Soviet Union to include large chunks of land that were linguistically and culturally Russian.9 The population problem was also significant in the former Baltic republics, especially Latvia and Estonia, and in Georgia.

In 1989, ethnic Russians were 22.1 percent of Ukraine’s population of 51.5 million.10 As shown in Map 1, Russian-language speakers have been heavily concentrated in the east and south of the country, in lands that had historically been part of Russia. That pattern of concentrated numbers of Russian-language speakers meant that Ukraine was politically divided and, in a worst-case scenario, primed for civil war and secession.

Map 1. The Languages of Ukraine

Source: “Languages of Ukraine,” Reconsidering Russia and the Former Soviet Union blog, updated May 15, 2014, reconsideringrussia.org.

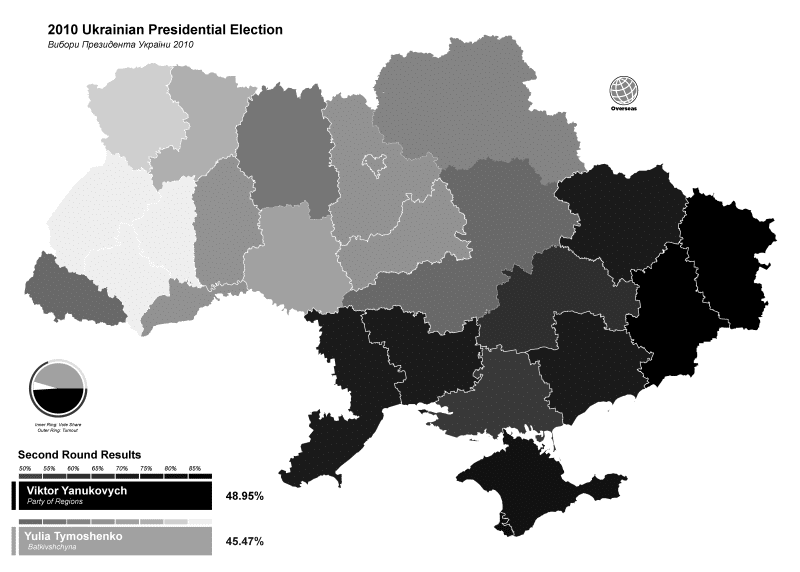

The stark political division is illustrated in Map 2, which shows the winning vote share by oblast (province) in the second round of the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election. The eastern half of the country voted solidly for Yanukovych; the western half solidly for nationalist Yulia Tymoshenko.

Map 2. Second-Round Results of the 2010 Presidential Election

Source: Central Election Commission of Ukraine, “Voting Results: Support for Leaders by Region,” updated January 17, 2010, cvk.gov.ua.

The stranded ethnic Russian population problem then intersected with the problem of national animosities as the newly independent republics pursued nationalist cultural cleansing policies that sought to erase the history and presence of Russian culture and language. Such cultural cleansing constitutes a form of political intimidation and discrimination. Once again, Ukraine was the worst on those counts, followed by the Baltic republics. Ukraine’s cultural cleansing is evident in a series of progressively more intolerant laws making Ukrainian the only official language and banning Russian. It is also evident in the outlawing and tearing down of monuments honoring Russian historical cultural and political figures, which has accelerated in the wake of Russia’s intervention.11

Lastly, the fate and treatment of the stranded populations was also of political concern to Russia for reasons of ethnic identification. These populations had been citizens of the Soviet Union, and they became politically separated from Russia owing to the USSR’s unexpected disintegration. Although they were not Russian citizens under the terms of the breakup, they were historically connected to Russia, by language, culture, and identity, and inclined to think of themselves as Russians. Consequently, the stranded Russian populations provided an opening for Russia to establish a degree of soft power within former republics. Moreover, many Russian-speaking Ukrainians in the East and South had Russian as well as Ukrainian citizenship.12

The third fracture concerned contested territories. That fracture was initially the least important, but it has gradually risen to become a defining issue. Russia has always felt territorially shortchanged by the breakup of the Soviet Union. Additions in the eastern and southern parts of Ukraine in 1922 and 1954, respectively, were made when Ukraine and Russia were joined at the hip via the Soviet Union and breakup was deemed unimaginable. Despite that, Russia initially accepted the new borders via the 1994 Bucharest Memorandum agreement with Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine. In return for border recognition, the three former republics returned all nuclear weapons and signed the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.13 Additionally, the problem of Russia’s Black Sea naval base in Sevastopol was solved by a long-term lease arrangement signed in 1997 and extended in 2010 by the Kharkiv Pact.14

That fragile territorial equilibrium was shattered by the U.S.-supported 2014 Maidan coup, which overthrew the elected president and installed an anti-Russian nationalist. The Russian response was to annex Crimea with strong Crimean support from its largely Russian-speaking population following a plebiscite. Civil war also erupted within Ukraine, with parts of the four eastern Donbass oblasts refusing to accept the legitimacy of the coup. That fused the territorial fracture with the issue of the stranded ethnic Russian population.

There then followed a second fragile equilibrium, in which Russia sought to work with NATO to resolve the Civil War via the Minsk peace process that was initiated in 2014. The process aimed to end conflict in the Donbass and find a political solution that granted the region a mutually acceptable degree of autonomy.15 That second equilibrium became increasingly frayed and finally collapsed with Russia’s 2022 military intervention and annexation of the Donbass oblasts. That annexation has elevated the contested territories fracture into a codefining issue, along with Ukraine’s relationship to NATO.

The External Blade: The Geopolitical Drivers of Conflict

The other blade of the conflict scissors is the external drivers of conflict, of which there are four. They consist of the U.S.-led eastward expansion of NATO, U.S. internal intervention in Ukraine, U.S. neoconservative geopolitical strategy (reinforced by the U.S. military-industrial complex), and so-called democracy promotion. The United States is the force behind all four external drivers, which is why it can be legitimately said that Washington has provoked and sustains the conflict.

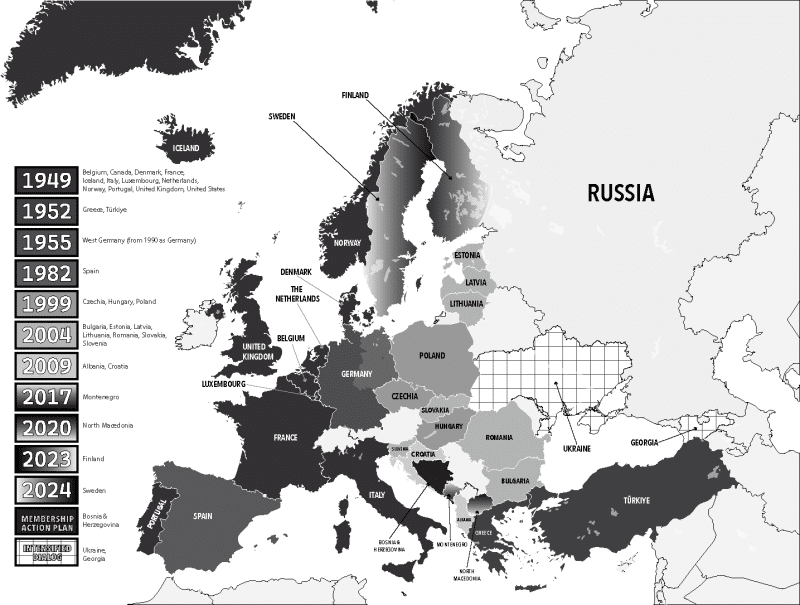

The first and most important external driver is the U.S.-led eastward expansion of NATO. That expansion is detailed in Map 3, which shows NATO accession dates by country.16 The expansion agenda emerged out of Washington and was officially greenlit by the Bill Clinton administration in 1994.17

Map 3. NATO Enlargement since 1949

An undisputed fact is that, except for East German membership, Russia has persistently objected to this expansion. Its argument has consistently been that eastward NATO expansion poses a threat to Russian national security. Russia also claims that it violates the agreement with and assurances given to Gorbachev as part of ending the Cold War and dissolving the Warsaw Pact.18 In 1994, President Boris Yeltsin furiously and openly objected to NATO expansion in his summit with Clinton.19 That episode long precedes the rise of Vladimir Putin, who has been tarred by Western media as a bogeyman, and shows that the consequences of NATO expansion cannot be laid at Putin’s doorstep. Yeltsin was the partner for peace, yet already the United States and Europe had reneged on the understanding struck with Gorbachev that ended the Cold War.20

From a strategic perspective, Map 3 reveals a three-stage process. Stage 1 was the 1999 incorporation of major Central European former Warsaw Pact countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland). Stage 2 was the 2004 incorporation of the former Baltic republics (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania), which marked a ratcheting up of the process by including elements of the former Soviet Union that bordered Russia. It also created a NATO “iron curtain” running from the Baltic to the Black Sea. Stage 3, which remains unfinished, concerns the intensified dialogues with Ukraine and Georgia, which aimed to incorporate those former Soviet Republics into NATO. This would massively expand NATO’s penetration of the former Soviet Union and widen its encirclement of Russia. (A Stage 4, subsequent to the onset of the Ukrainian-Russian War, was the incorporation of Finland and Sweden into NATO in 2023 and 2024, respectively).

Furthermore, Ukraine juts like a spear into the heart of Russia. At its closest point, its border is just three hundred miles from Moscow. Consequently, incorporation of Ukraine into NATO would strip Russia of its historically critical land buffer, and NATO short- and medium-range missiles could threaten the Russian heartland. All those fears have been proven true by the current conflict.

For those reasons, the threat posed by Stage 3 has proven the straw that broke the camel’s back. Thus, Russia responded with military force to prevent further expansion. In 2008, Russia intervened with force to stop a U.S.-encouraged attempt by Georgia to reoccupy South Ossetia and, in 2014, it intervened in Ukraine. The Georgia conflict has gone silent, but in Ukraine it has tragically deepened because of far worse internal fractures and U.S. internal interventions.21

The expansion of NATO raises several questions, the first of which is: Did expansion breach the agreement made with Gorbachev? No formal treaty detailing a promise not to expand NATO beyond East Germany was ever signed. That said, there is evidence that promises were made to Gorbachev that there would be no further expansion. The most compelling evidence is that of U.S. Ambassador Jack Matlock Jr., who was the last U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union. He reports that at the 1989 Malta Summit—which ended the Cold War—George H. W. Bush gave unambiguous promises that there would be no NATO expansion.22 Swiss journalist Guy Mettan also documents how non-expansion security guarantees were given by U.S. Secretary of State James Baker, German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, and French President François Mitterrand.23

Even counterfactually, assuming there was no promise of non-expansion, there remains the fundamental question of why NATO was expanded. NATO was founded as a “defensive” alliance, which is its charter mission. It is easy to understand why Poland, Romania, and the former Baltic republics would want to join NATO to secure defensive protection. However, the proper question, which is never asked, is: Why did the United States or the United Kingdom want them to join? The new member countries brought modest military capabilities and bucketloads of conflict risk. In other words, they were a net negative security addition to existing NATO members, measured in terms of NATO’s original stated purpose as a defensive alliance.

In a similar vein, there was no “balance of power” rationale for expanding NATO, as the Warsaw Pact was formally dissolved on February 25, 1991. Balance of power considerations have historically motivated the structure of continental European alliances, and the balance had indisputably and comprehensively shifted in favor of NATO. According to that criterion, expanding NATO was unambiguously aggressive.24

Finally, there is the simple question of: how is U.S. national security enhanced by having its military on Russia’s border, six thousand miles away from the eastern United States, on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean? The answer is it is not. That shows the motive for NATO expansion was never about U.S. national security, but rather U.S. global hegemony. Asking the right question makes crystal clear NATO expansion was an aggressive move against Russia.

A third question is: Was NATO expansion a kind of bumbling error with unanticipated consequences? The answer is that it was not, and that answer is also crystal clear. Russia openly expressed its hostility to NATO expansion, as evident in the 1994 blow-up between Clinton and Yeltsin in Budapest, when Yeltsin furiously objected to plans to expand NATO.25 Likewise, in 2007, Putin openly and vehemently objected to NATO expansion at the Munich security conference.26

The issue of NATO expansion was also debated in the United States, and critics openly stated that a major consequence would be conflict with Russia. The most famous of these critics was George Kennan, founder of the “Containment Doctrine” that guided U.S. Cold War strategy. In a 1997 New York Times op-ed titled “A Fateful Error,” Kennan wrote that NATO expansion was a mistake that would lead to conflict.27 Awareness of these consequences is evident from the scale and standing of the opposition to NATO expansion. This is visible in a 1997 letter to Clinton that was signed by fifty leading U.S. senior politicians, national security and foreign policy experts, and former high-ranking military and intelligence officers. Signatories included Senator Bill Bradley, former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, defense expert and former State Department official Paul Nitze, Senator Sam Nunn, and former CIA director Stansfield Turner.28 The letter described NATO expansion as “a policy error of historic proportions” that would lead Russia “to question the entire post-Cold War settlement.” Yet expansion proceeded, with the first batch of new members being admitted in 1999.

The proposed expansion of NATO to include Ukraine was also discussed, and its consequences were also foreseeable and foreseen. The clearest statement of those consequences is in a confidential February 2008 letter (made available via Wikileaks) in which U.S. Ambassador to Russia William Burns (later to become CIA chief) warned that it would unambiguously cross Russia’s national security red lines.29

The second external driver of conflict is U.S. internal intervention in Ukraine. Much of the evidence for that intervention concerns Victoria Nuland, who in 2014 was U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs and is deeply embedded in the U.S. neoconservative movement. Moreover, she has continuously held important positions in the George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Joe Biden administrations, revealing the bipartisan character of U.S. policy on Ukraine. In the second Bush administration, she was U.S. ambassador to NATO from 2005 to 2008. In December 2013, Nuland revealed that the United States had spent $5 billion on aid to Ukraine, classified as “democracy building.” During the 2014 Maidan coup, she made several public appearances in Kiev supporting the coup activists, and a telephone call between her and U.S. ambassador to Ukraine Geoffrey Pyatt was recorded. The call suggested the United States was actively intervening in Ukrainian political developments, including actively seeking to obstruct European Union peace efforts, with Nuland declaring “F––k the EU.”30

Five billion dollars was (and is) an extraordinarily large amount of money in a poor country like Ukraine that was also short of foreign currency.31 U.S. “democracy-building” money is funneled through government agencies such as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the National Endowment for Democracy, both of which have been widely accused of meddling and political interference abroad.32 USAID has a legal mandate to ensure its economic support is consistent with U.S. geopolitical interests. It has a long history of cooperation with the CIA and works closely with the U.S. State Department with an obligation to promote U.S. foreign policy interests. Consequently, such money tends to be channeled to actors aligned with U.S. geopolitical interests—which, in the case of Ukraine, meant weakening sympathies and links with Russia.

After the Maidan coup, the United States stepped up its weapons deliveries to Ukraine. The Washington-based Stimson Center reported that Ukraine received over $2.7 billion in military assistance between 2014 and 2021. Between 2016 and 2020, Ukraine was the seventh-largest recipient of U.S. military assistance, and the largest European recipient. That assistance had the United States stepping directly into Ukraine’s civil war on behalf of the nationalist government that resulted from the Maidan coup. This assistance was also instrumental in prompting Russia to intervene in Ukraine in February 2022.33

Eastward expansion of NATO and internal intervention in former Soviet Republics (especially Ukraine) are the “means” whereby the United States has exploited fractures in the post-Soviet order and provoked conflict. The next piece of the puzzle is “why” the United States chose to go in that direction. The answer lies in U.S. politics, the triumph of the neocon movement, and the power of the military-industrial complex.

The third external driver of U.S. intervention in Ukraine is neoconservatism, a U.S. political doctrine that rose to ascendancy in the 1990s. It holds that never again shall there be a foreign power, such as the former Soviet Union, that can challenge U.S. global hegemony. The doctrine gives the United States the right to impose its will anywhere in the world, with the result that the United States has over 750 bases in more than eighty countries, ringing both Russia and China.34

The neocon objective is U.S. global hegemony. That objective has driven both eastward expansion of NATO and interference in former Soviet Republics aimed at fostering anti-Russian sentiment and provoking conflict with Russia. The neocon doctrine initially seeded itself among hardliner Republicans like Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld, and was then adopted in the 1990s by Democrats under the leadership of Clinton. Consequently, it became a bipartisan U.S. consensus. Moreover, the Democrats added insidious cover by claiming the U.S. motivation is promotion of democracy and human rights, which provides a fig-leaf cover for the goal of U.S. global hegemony.35

Regarding Russia, the neocon playbook was explicitly laid out by former U.S. National Security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski in 1997 in a Foreign Affairs article and a book titled The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives.36 Brzezinski was a key figure in the formation of both Cold War and post-Cold War U.S. policy. His views reflect his belief in U.S. neoconservative doctrine and his deep animus toward Russia.37 The goal was ensuring U.S. global supremacy. The recommended strategy was incrementally surrounding and isolating Russia via NATO expansion, combined with intentional detachment of Ukraine from Russia. Brzezinski viewed Ukraine as essential to Russian power, writing: “Ukraine, a new and important space on the Eurasian chessboard, is a geopolitical pivot because its very existence as an independent country helps transform Russia. Without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be a Eurasian empire.”38

Furthermore, Brzezinski casually floated the idea of dismembering Russia, speciously proposing it to be in Russia’s interests: “A loosely confederated Russia—composed of a European Russia, a Siberian Republic, and a Far Eastern Republic—would also find it easier to cultivate closer economic relations with Europe, with the new states of Central Asia, and with the Orient, which would thereby accelerate Russia’s own development.”39

Brzezinski’s writing spoke to the level of U.S. aggression against Russia and foreshadowed what has followed with extraordinary detail, to the extent of almost constituting a self-incriminating neoconservative master plan. The short-term plan was NATO expansion; the medium-term plan was turning Ukraine against Russia and detaching it from Russia; and the long-term plan was dismembering Russia. Viewed in that light, U.S. intervention in Ukraine was a stepping-stone to further attacks on Russia.40

Neoconservative doctrine guides U.S. geopolitical thinking and strategy, and it is supported by the military-industrial complex. That complex binds the U.S. military, the Defense Department and associated bureaucracies, and the massive defense industry, which supplies the military. This creates a hugely powerful political-economic interest that significantly determines foreign and national security policy. Moreover, the influence of the military-industrial complex ripples deep into U.S. society. It influences Congress via political campaign contributions and promises of jobs and consultancies to politicians. It also exerts a massive influence on public opinion and public understanding of national security via a network of financial sponsorship that includes the mass media, think tanks, universities, and the film and video game industries.41

The critical point is that the end of the Cold War promised a major reduction in military spending, which posed a huge economic threat to the military-industrial complex. The neocon project defused that threat. It provided a justification for continued Cold War-level military spending and more. Additionally, that spending can continue forever, because maintaining hegemony is a project without end.

An additional piece of the puzzle is European complicity with the U.S. neoconservative project, exemplified by Europe’s willing support of eastward NATO expansion and Europe’s sabotage of the 2014 Minsk peace process. Prima facie, Europe’s support is a puzzle because Europe has lost out economically from the rupture of relations with Russia and has borne the socioeconomic blowback (for example, the flow of refugees) from the conflict.

Further reflection reveals multiple explanations. The most compelling is that Europe’s military and foreign policy apparatus has been hacked by the United States, and it now serves U.S. rather than European interests.42 The hacking process has the U.S. government and its corporate partners placing a heavy thumb on the political scales of European countries. They do so by assisting amicable politicians, promoting supportive journalists and academics, and providing friendly political interests with financial and media support. Talking-class professionals (journalists and academics) are helped with career advancement.

Europe also has its own military-industrial complex, which is tied at the hip to the United States via NATO. Additionally, Europe’s defense industry wants to supply the U.S. military, the world’s biggest purchaser of equipment, and that requires supporting U.S. policy. Finally, history should not be neglected. Europe’s elites have their own long-standing animus toward Russia, which is especially acute in the United Kingdom, and, to a lesser degree, in Germany.43

The fourth external driver of conflict has been the myth of democracy promotion, whereby a benevolent United States is dedicated to globally promoting and protecting democracy. As mentioned, that story has been especially embraced by liberal Democrat neocons. The democracy promotion myth traces back to the nineteenth-century notion of American exceptionalism, which promoted the idea that the United States was an exceptional nation measured in terms of its ethical character and having a special mission. That idea is now bipartisan. For Republicans, the special mission is framed in terms of protecting and expanding freedom. For Democrats, it is framed in terms of a duty to safeguard and expand democracy.44

The democracy promotion narrative is a myth, and debunking it involves a long history of international relations that is far beyond the scope of this article. For current purposes, what matters is to recognize how the narrative has helped drive conflict in Ukraine. Here, it is important for three reasons. First, it has provided Western public opinion with justification for both eastward expansion of NATO and intervention in Ukraine and former Soviet Republics. Second, it has mobilized U.S. and Western public opinion against Russia, and it keeps public opinion supportive of the war. Third, it has masked the reality of the motives behind the eastward expansion of NATO and internal intervention in Ukraine. Metaphorically speaking, the eastward expansion of NATO and U.S. intervention in Ukraine have both surfed on the back of the democracy promotion narrative.

In effect, the democracy promotion myth has been critical for mobilizing Western public opinion on behalf of the neoconservative project, and here it does double duty. First, it enlists public support for the U.S. project of global hegemony by tricking the public into seeing aggressive U.S. interventionism and militarism through the benevolent lens of democracy promotion.

Second, it suppresses U.S. domestic opposition to such policies, with the myth creating a form of intellectual tunnel vision. The public is inhibited from seeing the reality of pursuit of selfish national interest, despite a long history of such action—some of which violates international law and includes the overthrow of democratic governments. Furthermore, those who challenge the narrative risk being tarred as unpatriotic and undemocratic.

Since the myth facilitates the neoconservative project, the democracy promotion narrative is embraced by the military-industrial complex, which profits from that project. In effect, the narrative greenlights military spending and foreign interventions in the name of protecting and promoting democracy.

Over the last decade, the democracy promotion myth has been joined by a new myth of “Autocracy Inc.,” according to which the United States confronts an existential threat from foreign autocrats who seek to topple Western democracies and establish their own domination thereover. The Autocracy Inc. myth ramps up the case for U.S. interventionism, militarism, and military spending. Now, not only is the United States protecting and promoting democracy (the old “American exceptionalism” trope), but it also faces an existential threat from foreign autocrats. That new narrative creates a scenario of perma-conflict, justifying further increased military spending without a time limit. In the view of the military-industrial complex, this is even better than the Cold War, an end to which could be negotiated. According to the Autocracy Inc. narrative, no such negotiation is possible.45

The democracy promotion narrative and its newer Autocracy Inc. sibling are extremely dangerous. The former encourages self-righteous interventionism, while the latter promotes paranoia. Each alone would be dangerous; together they risk being catastrophic. They both encourage foreign policy aggression and military interventionism while cloaking such behaviors as “benevolent selflessness” and “self-defense.” Both are now being employed to drum up public support for sustaining the Ukraine conflict.

The toxic effect of the myths works via their capture of Western public opinion. Shifting public opinion away from support for war is essential to ending the Ukraine conflict and preventing future conflicts. Changing public opinion is also needed as a check on the military-industrial complex and neoconservative dominance of the U.S. political establishment. Unfortunately, public opinion has been captured by the self-righteous crusading narrative of democracy promotion and the paranoid Manichaean “good versus evil” narrative of Autocracy Inc., which pushes policy in the opposite direction. Those twin narratives render compromise almost impossible, encourage conflict intensification, and strengthen the political grip of the neocons and military-industrial complex.

No algebra can discredit such thinking. All that is possible is appeal to logical argument, evidence, and history. Here, disdain for history kicks in again. The lack of interest in history means there is little likelihood of changing public understanding. Furthermore, the U.S. establishment has no interest in doing so. Instead, the opposite is true. The establishment wants to sustain and nurture existing misunderstandings.

Worse yet, the more the United States (with NATO help) seeks to impose global hegemony, the more it prompts other countries to respond and build up their armed forces. Additionally, economic sanctions by the West compel countries to find other economic partners. Consequently, the United States creates a self-fulfilling prophecy as countries under threat from the United States will tend to cluster economically, diplomatically, and militarily. However, that clustering is defensive and not offensive, as claimed by the Autocracy Inc. myth.

The Outbreak of War: Russia’s Military Intervention Explained

I have used the metaphor of a scissors to explain the conflict. The internal fractures in the post-Soviet order constitute one blade. The external factors associated with U.S. intervention constitute the other blade. Nationalist animosities are the pivot point joining the blades together. Those animosities created internal divisions within former republics. They also provided the entry point for the United States to insert NATO into the Baltic republics, as well as for internal interventions in other former Soviet Republics. Thus, these animosities served both blades.

Russia’s 2022 intervention should be understood as an escalation of a conflict that had already been triggered by the 2014 Maidan coup. Pre-2014, Russia persistently opposed the expansion of NATO but reluctantly accepted it. The 2014 coup was the straw that broke the camel’s back, prompting secession in the Donbass oblasts and Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

Thereafter, the Minsk peace process (2014–2021) created a period of “phony war” that delayed full-blown hostilities. Russia appears to have engaged in the process in good faith, though its critics claim its demands were unacceptable. However, France and Germany (the Normandy Group) who represented the U.S./NATO bloc appear to have acted in bad faith. In a December 7, 2022, interview with Die Zeit, former German Chancellor Angela Merkel admitted that the Minsk Accord was “an attempt to give Ukraine time” in which to strengthen itself while the United States provided massive military assistance.46

Russia’s military intervention in Ukraine seems to have been prompted by a double trigger of diplomatic and military developments. On the diplomatic side, there was Clause 69 in NATO’s Brussels Summit declaration of June 14, 2021, which enshrined the hardline U.S. position that Ukraine had a pathway to NATO membership, regardless of Russian objections.47 That position was reaffirmed with even stronger language in the November 2021 bilateral strategic partnership signed by the United States and Ukraine.48

On the military side, in February 2022, there was evidence of an imminent Ukrainian military offensive against the Donbass secessionists, with Ukrainian forces now equipped with a decade of U.S. military support. Such an offensive might have defeated the secessionists, putting Russia’s hold on the Crimea at risk. Russia’s military intervention preempted that outcome.49

A balance sheet accounting of the war has Ukraine and Europe being clear losers. Russia’s situation is complicated but net positive. The United States is a clear winner, at least in the short term. Ukraine is the biggest loser. Its economy and infrastructure have been decimated, large swathes of land have been mined or captured by Russia, millions have fled the country as refugees, tens of thousands have been killed or wounded, democracy is suspended, the proto-fascist extremists are politically in charge, and the country has many of the characteristics of a failed state.

Europe is also a major loser. It is suffering large Ukrainian refugee inflows and the socioeconomic costs and adverse political backlash that they generate. The economic costs have been especially large. European energy prices stand to be permanently higher due to the loss of cheap Russian energy supplies. The jump in energy prices caused temporary inflation and will result in permanently lowered real incomes and loss of international industrial competitiveness, adversely impacting its manufacturing sector. Europe has also forfeited the economic opportunity of capital goods exports to Russia owing to sanctions. Its beneficial trade and investment relationship with China is also being undermined, as the United States is insisting NATO allies move to a war footing vis-à-vis China, which is supportive of Russia and rejects U.S. global hegemony.50

Russia’s position is mixed but is net positive. On the one hand, it has suffered tens of thousands of casualties and the destruction of much military hardware. It has also suffered loss of economic opportunity owing to sanctions and severing of trade opportunities with Europe, and there is the unresolved issue of the West’s impounding of its foreign exchange reserves. On the other hand, it has achieved its goal of checking the U.S. project of incremental strategic threat escalation that slowly erodes Russia’s security, and it has also substantially achieved its goal regarding neutralizing the security threat posed by Ukraine joining NATO. The war has also provided a reality check for the Russian military that promises to deliver future military improvements.

Additionally, Russia may reap important economic benefits, as the war has given Putin political power to crack down on corruption and diminish the power of oligarchs.51 It is also benefiting from an economic pivot to military Keynesianism and social democratic Keynesianism. As argued by James K. Galbraith, the sanctions regime has been a form of policy gift, enabling and prompting Russia to implement a pro-development policy that it might have been politically unable to undertake otherwise.52 An open issue is whether China and other countries can step in and supply the advanced technology products that the U.S./NATO bloc refuses to supply.

In the short term, the United States is the chief winner from the conflict, which helps explain the Biden administration’s determination to prolong and escalate the conflict. It has suffered no direct battlefield damage from the conflict, whereas Russia is suffering ongoing military losses. Economic damage to the United States has been limited to some temporary commodity inflation in 2022, and it has been offset by the benefits of military Keynesian stimulus that goes with providing weapons to Ukraine. Most importantly, the United States has stepped into Russia’s shoes as an energy supplier to Europe. That has increased U.S. energy exports and benefited the economies of its Gulf Coast states. Geopolitically, it has also rendered Europe dependent on U.S. energy while separating Europe from Russia, which fits with the U.S. project of global hegemony. Similarly, the accompanying ratcheting up of economic tensions between Europe and China also serves that project, with Europe again bearing large costs from trade and investment losses.

In the long term, the balance sheet looks worse for the United States for geostrategic reasons. First, except for NATO and the Pacific countries allied with the United States, most of the world appears to see some merit in Russia’s security claims. Second, and most importantly, the United States has succeeded in consolidating a comprehensive strategic Sino-Russian alliance that stands to permanently diminish its power and undercut the project of U.S. global hegemony. Unfortunately, those long-term adverse effects have little bearing on the conflict as they are largely irreversible, whereas the short-term benefits continue to flow. That configuration gives the U.S. establishment an incentive to continue the war.

In Ukraine, democracy is suspended and internal opposition to the war is suppressed. The nationalist extremists control the military and are the dominant political force, with President Volodymyr Zelensky as figurehead. That means Ukraine is also locked into conflict, as the nationalists are unwilling to compromise.

Russia is slowly grinding toward a victory of arms, with the risk of a nuclear event ever-present. It deems Ukrainian NATO membership an existential security threat, and its fears have been substantially validated by the war. It has also spent much blood and treasure for its war gains, which it will not surrender.

The above assessment suggests the outlook and prognosis for peace are grim, and the conflict is likely to continue until either the battlefield outcome is decisively settled or Western public opinion changes. The war should never have happened. The United States green-flagged Ukraine’s adoption of positions that would lead to conflict, and it then blocked all attempts to prevent the emerging conflict. The United States at present continues to enable Ukraine to keep fighting by resupplying destroyed weaponry and by providing additional advanced weaponry, technical assistance, and military intelligence.

The fateful 2014 Maidan coup set the ball rolling. The Minsk peace process offered an off-ramp, but it has now been revealed that the United States and NATO were not interested in such a de-escalation. Instead, France and Germany stalled the process, buying time for the United States to arm Ukraine, with the goal being defeat of the Donbass secessionists. Russia’s proposal for a Ukraine treaty settlement in November 2021 offered the last opportunity for peaceful resolution centered on a demilitarized, NATO-free Ukraine, but that proposal was dismissively rejected by the Biden administration. Peace negotiations between Russia and Ukraine in Istanbul in March 2022 offered an opportunity for a quick end to the war, but that was again blocked by NATO, with British Prime Minister Boris Johnson as the U.S. proxy.

The war has not changed attitudes, but negotiation possibilities have narrowed and worsened. Prior to the 2014 Maidan coup d’état, a modus vivendi was possible, with Ukraine retaining its 1922-based borders and Russia holding a lease on the Sevastopol naval base, as per the 2010 Kharkiv Treaty. The 2014 coup took that off the table permanently, with Russia reclaiming Crimea, which Khrushchev had gifted to Ukraine in 1954. The 2022 war has further changed the situation, with Russia annexing the Donbass oblasts that were incorporated in Ukraine in 1922.

Before 2014, Ukraine could have readily negotiated an accord with Russia. Now, that possibility is substantially blocked for both internal and external reasons. Internally, Ukraine’s extremist nationalists have acquired absolute political and military control so that domestic political opposition to the war is impossible. Those extremists are willing to fight to the last Ukrainian. Externally, Ukraine’s nationalists are beholden to the United States, as their military and political position would collapse absent continued U.S. support. That dependence gives the United States huge sway, and the United States has wanted the war to continue, since it bears little cost and sees benefits in the damage being inflicted on Russia.

In effect, Ukraine’s nationalists made Ukraine a “sacrificial pawn” in the project of U.S. global hegemony. That role now consigns ordinary Ukrainians to fight a war of attrition against Russia over which they have no say. The war will only end when either Russia prevails on the battlefield, the war goes nuclear, or U.S. policymakers rethink the merits of the war.53 Unfortunately, neocons have ideologically based difficulties compromising or retreating, as that constitutes a tacit surrender of U.S. hegemony. Consequently, if the neoconservative position prevails, that will lock the United States into keeping the conflict going. That means shifting Western public opinion to compel the United States to accept a compromise with Russia, critical for ending the war.

Conclusion

In this article, I have explored the deep causes of the Ukraine war and argued that the war has both internal and external causes. The internal causes are rooted in the way the Soviet Union disintegrated. The external causes relate to how the United States exploited the fractures in the post-Soviet order to advance its neoconservative agenda aimed at establishing U.S. global hegemony.

The war has devastated Ukraine. It has destroyed Ukraine’s economic foundation, triggered mass population flight, caused tens of thousands of deaths, and solidified the fascist nationalist grip on political and military power. Assisted by the United States, Ukrainian nationalists captured Ukrainian politics and refused to compromise with the complicated political and demographic reality of post-Soviet Ukraine. In doing so, they made Ukraine a sacrificial pawn in the U.S. project seeking global hegemony, with fateful consequences that may yet worsen further. Europe has also supported this folly at great cost to itself.

Notes

- ↩ Vladislav Zubok, Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2021). Branko Milanovic provides a concise review drawing parallels with Yugoslavia’s disintegration. See Branko Milanović, “Collapse—The Fall of the Soviet Union by Vladislav M. Zubok,” Brave New Europe, February 16, 2024.

- ↩ The famine was the product of the bad harvests of 1931 and 1932, combined with the Stalin regime’s policy of collectivization of agriculture. The regime believed collectivization was the way to secure increased food supplies to support industrialization and increased defense production. The greatest number of deaths in Ukraine was owing to the centrality of agriculture therein, but contemporary Ukrainian claims of seven to ten million Ukrainian deaths are overstated by a factor of between two and three. See R. W. Davies and Stephen G. Wheatcroft, The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931–1933 (Industrialisation of Soviet Russia) (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004 [2009]).

- ↩ See “Ukraine: Historical Background during the Holocaust,” Yad Vashem, yadvashem.org; G. Rossoliński-Liebe, “Holocaust Amnesia: The Ukrainian Diaspora and the Genocide of the Jews,” German Yearbook of Contemporary History, vol. 1 (Lincoln, Nebraska: Nebraska University Press, 2016), 107–43; and Ivan Katchanovski, “The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, and the Nazi Genocide in Ukraine,” paper presented at the Conference on Collaboration in Eastern Europe during World War II and the Holocaust, December 5–7, 2013, Vienna, Austria. As part of rehabilitating Ukraine in the eyes of Western public opinion, some historians are trying to downplay Ukraine’s responsibility in the Holocaust. A leading figure in this revisionist history is Yale historian Timothy Snyder, who writes “the majority, probably the vast majority of people who collaborated with the German occupation were not politically motivated. They were collaborating with an occupation that was there, and which is a German responsibility” (Timothy Snyder, “Germans Must Remember the Truth about Ukraine—For Their Own Sake,” Eurozine, July 7, 2017). Balanced against that, the Simon Wiesenthal Center reports Ukraine has never investigated a local Nazi war criminal or prosecuted a Holocaust perpetrator (see “Nazi Hunters Give Low Grades to 13 Countries, Including Ukraine,” Associated Press, January 12, 2011).

- ↩ Casey Michel, “The Covert Operation to Back Ukrainian Independence that Haunts the CIA,” Politico, November 11, 2022; Phil Miller, “When MI6 Betrayed Ukraine’s Resistance to Russia,” Declassified UK, March 16, 2023.

- ↩ Daniel Lazare, “Who Was Stepan Bandera?” Jacobin, September 24, 2015; Ido Vock, “Ukraine’s Problematic Nationalist Heroes,” New Statesman, January 5, 2023.

- ↩ “Who Are Ukraine’s Far-Right Azov Regiment?” Al Jazeera, March 1, 2022, updated June 12, 2024.

- ↩ Josh Cohen, “Dear Ukraine: Please Don’t Shoot Yourself in the Foot,” Foreign Affairs, April 27, 2015; Keith Darden and Lucan Way, “Who Are the Protesters in Ukraine?,” Washington Post, February 12, 2014; Anthony Faiola, “A Ghost of World War II History Haunts Ukraine’s Stand-off with Russia,” Washington Post, March 25, 2014.

- ↩ “Israel’s Ambassador Shocked by Lviv Region’s Decision to Declare Year of Bandera,” Kyiv Post, December 13, 2018; Jeremy Sharon, “Nazi Collaborators Included in Ukrainian Memorial Project,” Jerusalem Post, January 21, 2021.

- ↩ The territorial entity that is Ukraine is a product of the Soviet Union. It was created under the 1922 treaty that established the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Ukraine did not formally exist in Tsarist Russia, which was divided into guberniyas (governates) that had minimal correspondence with what became the republics.

- ↩ State Statistics Committee of Ukraine, “All-Ukrainian Population Census 2001: General Results of Census,” n.d.

- ↩ Regarding language policy, see Roman Huba, “Why Ukraine’s New Language Law Will Have Long-Term Consequences,” Open Democracy, May 28, 2019, opendemocracy.net. See also Agnes Dinyes, “Caught in the Crossfire: Minority Languages in Ukraine,” Minority Rights Group, October 11, 2023, minorityrights.org. On the destruction of monuments, see Helen Parish, “Soviet Monuments Are Being Toppled—This Gives the Spaces They Occupied a New Meaning,” The Conversation, September 5, 2022; and Sophia Kishkovsky, “Huge Soviet-Era Monument in Kyiv Taken Down as Ukraine Continues ‘Derussification,'” Art Newspaper, May 3, 2024.

- ↩ Öncel Sencerman, “Russian Diaspora as a Means of Russian Foreign Policy,” Military Review: The Professional Journal of the U.S. Army (March–April 2018): 41–49.

- ↩ “Ukraine: The Budapest Memorandum of 1994,” Harvard Kennedy School of Government, policymemos.hks.harvard.edu.

- ↩ Luke Harding, “Ukraine Extends Lease for Russia’s Black Sea Fleet,” Guardian, April 21, 2010.

- ↩ “What Are the Minsk Agreements on the Ukraine Conflict?,” Reuters, February 21, 2022.

- ↩ NATO expansion was U.S.-led, as the United States is the overwhelmingly dominant force in NATO and nothing happens without its affirmative consent.

- ↩ The White House, “Strengthening NATO and European Security,” Clinton White House Archives, n.d.

- ↩ There are multiple accounts of the expansion and Russia’s objections. For instance, see Joe Lauria, “Ukraine Timeline Tells the Story,” Consortium News, June 30, 2023; Jeffrey D. Sachs, “The Real History of the War in Ukraine: A Chronology of Events and Case for Diplomacy,” The Kennedy Beacon, July 17, 2023; and Ted Galen Carpenter, “Many Predicted NATO Expansion Would Lead to War. Those Warnings Were Ignored,” Guardian, February 28, 2022.

- ↩ National Security Archive, “NATO Expansion—The Budapest Blow Up 1994,” George Washington University, November 24, 2021, nsarchive.gwu.edu.

- ↩ Gorbachev’s aspirations and understanding of the settlement were laid out in his July 6, 1989, speech to the Council of Europe: Mikhail Gorbachev, “Address Given by Mikhail Gorbachev to the Council of Europe,” Strasbourg, July 6, 1989.

- ↩ It has been widely observed that the United States would never accept Russian missiles on its borders, as shown by the 1961 Cuban missile crisis. That observation speaks to the rationality of Russia’s objection to incorporation of Ukraine in NATO. It also speaks to the hypocrisy of U.S. actions and criticisms of Russia.

- ↩ Jack F. Matlock Jr., “Today’s Crisis over Ukraine,” American Committee for US-Russia Accord, February 14, 2022, usrussiaaccord.org.

- ↩ See Guy Mettan, “Truths and Lies about Pledges Made to Russia,” Swiss Standpoint, February 17, 2022, schweizer-standpunkt.ch.

- ↩ U.S. State Department “Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations: The Warsaw Treaty Organization, 1955,” n.d., history.state.gov/milestones.

- ↩ National Security Archive, “NATO expansion—The Budapest Blow Up 1994.”

- ↩ See Vladimir Putin, “Speech and the Following Discussion at the Munich Conference on Security Policy,” Munich, February 10, 2007, en.kremlin.ru.

- ↩ See George Kennan, “A Fateful Error,” New York Times, February 5, 1997.

- ↩ See “Opposition to NATO Expansion,” Arms Control Association, June 26, 1997, armscontrol.org

- ↩ See Wikileaks, “Nyet Means Nyet: Russia’s NATO Enlargement Redlines,” memorandum by William J. Burns, January 30, 2018.

- ↩ See “Ukraine Crisis: Transcript of Leaked Nuland-Pyatt Call (with Analysis by Jonathan Marcus),” BBC, February 7, 2014; and Daniel Larison, “Victoria Nuland Never Shook the Mantle of Ideological Meddler,” Responsible Statecraft, Quincy Institute, March 5, 2024.

- ↩ In 2014, Ukraine’s GDP was approximately $134 billion. Its low point in the modern era was $32 billion in 1999.

- ↩ See “National Endowment for Democracy,” Influence Watch, n.d., influencewatch.org.

- ↩ Elias Yousif, “U.S. Military Assistance to Ukraine,” Stimson Center, January 26, 2022.

- ↩ Mohammed Hussein and Mohammed Haddad, “Infographic: US Military Presence around the World,” Al Jazeera, September 10, 2021.

- ↩ Neoconservatism is formally identified with the Project for the New American Century (PNAC), which was launched in 1997. The cofounders of PNAC were William Kristol and Robert Kagan. The latter is married to Nuland, who played a leading role in pushing NATO’s eastward expansion and in the Ukraine policy of the Obama and Biden administrations. PNAC founding supporters dominated foreign policy during George W. Bush’s presidency (2001–2009). They included Cheney, Rumsfeld, and Paul Wolfowitz, who were instrumental in driving the 2003 invasion of Iraq. See Pierre Bourgois, “The PNAC (1997–2006) and the Post-Cold War ‘Neoconservative Movement,'” E-International Relations, February 1, 2020, e-ir.info. Subsequently, PNAC was replaced by the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) which was founded in 2007. The creation of CNAS was sponsored by Hillary Clinton and was strongly supported by Obama, showing how Democrats have become the most zealous supporters of neoconservatism and the project of U.S. global hegemony (“Center for a New American Security,” Militarist Monitor, October 13, 2014, militarist-monitor.org). Nuland is a former CEO of CNAS, showing her central role in the neoconservative project, working with both Republicans and Democrats.

- ↩ Zbigniew Brzezinski, “A Geostrategy for Eurasia,” Foreign Affairs (September/October 1997); Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives (New York: Basic Books, 1997). Foreign Affairs has a special quasi-official standing, being the premier journal of the elite U.S. foreign policy community.

- ↩ Brzezinski was born in Warsaw, Poland on March 28, 1928.

- ↩ Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard, 46.

- ↩ Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard, 202.

- ↩ The United States has faithfully followed this aspect of Brzezinski’s plan, but it has not followed his advice about not antagonizing China. Brzezinski saw a Russia-China alliance as a grave threat to U.S. hegemony and warned against antagonizing China over Taiwan by discarding the accord established by Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger regarding ultimate Chinese sovereignty. Instead, the 2012 Obama-Hillary Clinton pivot to Asia threatened China. That was ramped up by the 2016 Donald Trump nationalist-racist turn against China, and the entire Nixon-Kissinger settlement has been irreparably smashed by the embrace by Biden and Nancy Pelosi of Taiwan as an independent, sovereign entity.

- ↩ For a comprehensive analysis of the military-industrial complex and its activities, see Thomas Palley “The Military-Industrial Complex as a Variety of Capitalism and Threat to Democracy,” Review of Keynesian Economics 12, no. 3 (August 2024): 308–47.

- ↩ See Thomas Palley, “Europe’s Foreign Policy Has Been Hacked and the Consequences Are Dire,” Brave New Europe, February 15, 2024.

- ↩ In the nineteenth century, British animus toward Russia was rooted in fear that Russian expansion in Central Asia would threaten Britain’s hold on India. It was also driven by fear of increasing Russian influence in the declining Ottoman empire, which motivated the Crimean War. In the twentieth century through today, British animus toward Russia is rooted in the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution and the establishment of a Communist state, the execution of the tsar and his close family, and the Soviet Union’s default on First World War loans from Britain. That animus was drilled into Britain’s political and security apparatus by Winston Churchill, who remains an iconic figure in British politics.

- ↩ Adam Volle, “American Exceptionalism,” Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d.

- ↩ The Autocracy Inc. hypothesis is associated with journalist-historian Anne Applebaum. See Anne Applebaum, “The Bad Guys Are Winning,” Atlantic, November 15, 2021. This narrative is strikingly inconsistent with the facts. Autocrats tend to keep their countries walled off, and none of the countries in the narrative have the wherewithal to take on the United States and NATO. Instead, the evidence is the other way round, with the United States being the one that has covered the globe with bases, garrisons, and multiple massive fleets based in foreign ports. See Hussein and Haddad, “Infographic: US Military Presence around the World.”

- ↩ Kevin Liffey, “Putin Says Loss of Trust Will Make Future Ukraine Talks Harder,” Reuters, December 9, 2022.

- ↩ See NATO, “Brussels Summit Communiqué: Issued by the Heads of State and Government Participating in the Meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Brussels 14 June 2021,” press release, June 14, 2021.

- ↩ U.S. Department of State, “US-Ukraine Charter on Strategic Partnership,” press release, November 10, 2021.

- ↩ Jacques Baud, “The Military Situation in Ukraine,” Postil Magazine, April 1, 2022, thepostil.com.

- ↩ Michael Hudson has written insightfully about the U.S. attempt to detach Europe from Russia and make Europe economically dependent on the United States. Michael Hudson, “America’s Real Adversaries Are Its European and Other Allies,” CounterPunch, February 11, 2022; and Michael Hudson, “Germany as Collateral Damage in America’s New Cold War,” CounterPunch, April 1, 2024.

- ↩ Western media have exploited the issue of Russia’s oligarchs to drum up antipathy against both Russia and Putin. The reality is the oligarch class was the creation of the U.S.-sponsored economic reform program imposed immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union (1991–1994). The IMF’s “shock therapy” program privatized the Russian economy before an effective legal system was in place. The goal was to prevent the Russian state from ever resuscitating socialism. The oligarch class was created because it had access to Western credit and could scoop up assets at fire sale prices, assisted by corrupt party bosses and insider management. The oligarch class became extraordinarily politically powerful, enabling it to twist Russian policy. Ironically, the war and sanctions may have undermined the oligarchs’ power, freeing Russia to adopt more productive policies.

- ↩ James K. Galbraith, “The Gift of Sanctions: An Analysis of Assessments of The Russian Economy, 2022–2023,” Review of Keynesian Economics 12, no. 3 (August 2024): 408–22.

- ↩ In that regard, Germany is important as it is where public opinion is most likely to change, potentially fracturing NATO and causing the United States to rethink its position. Trump’s return to office also suggests a U.S. rethink. Trump is less antagonistic to Russia and more antagonistic to China, and therefore desirous of rupturing the Russia-China entente that the war has fostered.

Comments are closed.