Also in this issue

Article by Gabriel Matthew Schivone

- Tributes to Robert W. McChesney

- Genocide Denial with a Vengeance: Old and New Imperial Norms

- Humanitarian Imperialism: The New Doctrine of Imperial Right

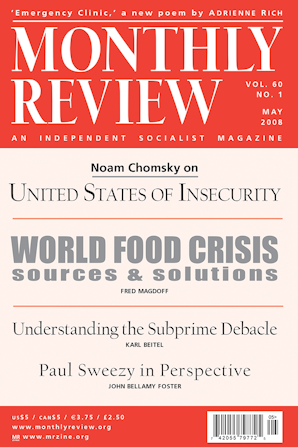

- Imminent Crises: Threats and Opportunities

- Imperial Ambition: An Interview with Noam Chomsky

- The United States is a Leading Terrorist State: An Interview with Noam Chomsky: An Interview with Noam Chomsky by David Barsamian