Also in this issue

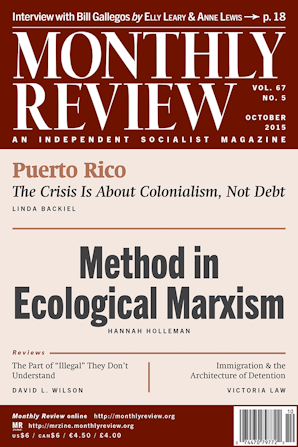

- Method in Ecological Marxism: Science and the Struggle for Change

- Puerto Rico: The Crisis Is About Colonialism, Not Debt

- Interview with Bill Gallegos

- Sic Vos Non Vobis (For You, But Not Yours): The Struggle for Public Water in Italy

- Stripping Away Invisibility: Exploring the Architecture of Detention