Andre Vltcheck has described Indonesia as an “archipelago of fear.”1 Much of that fear comes from one event: the mass killings of 1965–66. At least half a million people were killed—more than the U.S. losses in all wars up to that point. Most were beaten to death with logs and bricks, women had their breasts sliced off, and men were castrated. Bodies were piled up on rafts and sent down the river with the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) banner waving overhead.

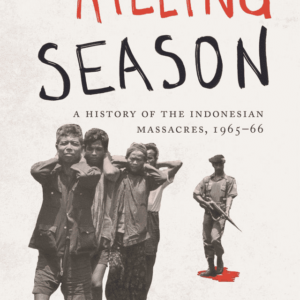

We learn of these grisly details in Geoffrey B. Robinson’s new book, The Killing Season: A History of the Indonesian Massacres, 1965–66. Robinson offers the most comprehensive history of the mass killings to date; one that provides a surprisingly revolutionary insight into what is to be done. “The most important insight from Indonesia,” Robinson writes, “is simply that power matters. As long as those responsible for the violence remain in power, the processes of truth seeking, justice, reconciliation, compensation, and memorialization are not likely to happen.”2 In other words, we must take power.

Robinson begins the book by contextualizing the events of 1965–66. In chapter 2, he situates the mass killings in the historical context of the Indonesian National Revolution. The need to fight a liberation war, he points out, militarized Indonesia’s state apparatus, creating a powerful, conservative military with a strong stake in the status quo. However, the need to galvanize the popular classes made emancipatory political doctrines the language of the day, portending the rise of the PKI and other left-wing forces. The army and the PKI were thus set on their collision course.

The clash of these two forces—the army and the PKI—took the form of the Gestapu (the Thirtieth of September Movement) and is the focus of chapter 3. Despite claims of being an officers’ movement, the Gestapu assassinated six right-wing generals, for which the army blamed the PKI and unleashed the mass killings. While much of the scholarship on the Gestapu focuses on the question of the Communists’ culpability, Robinson concludes that it is almost impossible—given the paucity of primary-source evidence—to discern who was really behind the movement. We should instead, he contends, focus on the real issue: the mass killings themselves.

Before moving on, however, Robinson documents how foreign powers meddled in Indonesia’s internal affairs, helping spark the Gestapu. The United States supported regionalist anti-Communist rebellions in Indonesia and actively sought to “accentuate political divisions and conflict inside the country, with a view to provoking a conflict from which the army could be almost certain to emerge victorious.”3 China, for its part, unsuccessfully attempted to arm the PKI before it was too late.

Robinson’s next three chapters (5, 6, and 7) focus particularly on the mass killings and the crucial question of responsibility. Chapter 5 examines the who, where, when, and how of the massacres and aims to dispel apologetic culturalist theories that try to pin the killings on communal and religious tensions. Robinson notes that the common denominator among those killed was not their religion or ethnicity, but their political affiliation. Moreover, the broad geographic scope of the killings suggests that they cannot be explained by local tensions. Robinson goes further, rebutting the narrative that the staggered timing of the killings indicates their spontaneity. Rather, it suggests that officers in different regions had different capacities to carry out a centrally issued order. In fact, the killings began later in the regions where the left was strongest. The similarities in the style of executions suggest that they were done in accordance with a plan and were not simply the result of organic tensions.

Robinson places the responsibility of the mass killings squarely on the army. Without the army’s logistic and leadership resources, the scale of the systematic mass violence witnessed would have been impossible. While the resources provided by the army were often used by civilian militias, these militias rarely killed unless provoked by the military. Moreover, the army learned how to mobilize civilian militias from the Japanese in the Second World War and then employed this “repertoire of violence” during the mass killings.

In chapter 7, Robinson also holds Western foreign powers—the United States and United Kingdom in particular—responsible for the killings. He provides rich documentary evidence pointing to the provision of cash, covert aid, equipment, intelligence, psywar (psychological warfare), and informal guarantees of amnesty, emboldening the army to move forcefully against the PKI.

In the following chapter, Robinson examines the program of mass incarceration that followed the mass killings. If there was any doubt as to the systematic nature of the mass killings, the mass incarceration puts them to rest. Imprisoning up to three million people for over a decade cannot be done any way but systematically. Robinson also documents the “stubborn resolve” and “pride and dignity” of many prisoners despite their horrendous conditions and routine torture, pointing to one of history’s greatest lessons: hope.

In chapters 9 and 10, Robinson documents contemporary efforts for justice. The international movement for human rights in Indonesia grew out of a small nucleus of Dutch socialist women and became a major force capable of compelling Suharto to release all of Indonesia’s tapol (political prisoners) by 1979.4 However, a program of mass surveillance, discrimination, and harassment was quickly instituted to replace the mass incarcerations.

While the fall of Suharto—who took power after the Gestapu and remained in power for more than three decades—in 1998 opened the way for significant advances, the movement has since suffered a split between proponents of reconciliation and those who consider truth and justice paramount. Moreover, Robinson notes a worrying level of grassroots resistance to rectification, stressing the importance of cultural initiatives like Joshua Oppenheimer’s documentary film The Act of Killing and the artwork of Komunitas Taman 65 in weakening that resistance.

Robinson concludes the book by way of synthesis and prescription, calling for immediate action on three main fronts: (1) breaking the silence on the 1965–66 mass killings and incarcerations in any way possible, (2) pressuring governments to open the archives on what happened during that period, and (3) pressuring them to prosecute those responsible.

While compelling and excellently researched, The Killing Season ignores the role of monopoly capital in the mass killings. While Robinson rightly holds the army and foreign powers responsible for the massacres, he glosses over the economic interests they protect. Hilmar Farid, Malcolm Caldwell, and Ernst Utrecht have noted that the main reason the United States and its allies supported Suharto in 1965 was to defend the profits of their multinationals.5 Moreover, as Intan Suwandi has shown, contemporary multinationals are as invested—if not more so—in the superexploitation of countries in the Global South such as Indonesia.6 Ultimately, bringing the army to account is not enough. We have not seen a decline in the influence of the army’s 1965 narrative concomitant to the decline in the army’s power in the post-Suharto period. The army, foreign governments, and monopoly capital must all be jettisoned from Indonesia’s ruling coalition for meaningful justice to be achieved.

Notes

- ↩ Andre Vltchek, Indonesia: Archipelago of Fear (London: Pluto, 2012).

- ↩ Geoffrey B. Robinson, The Killing Season: A History of the Indonesian Massacres, 1965–66 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018), 311.

- ↩ Robinson, The Killing Season, 96.

- ↩ Robinson, The Killing Season, 188. When the Gestapu happened, Suharto was the commander of the army’s strategic reserve, KOSTRAD. He took control of the army on the morning of October 1, 1965, and the army crushed the movement under his command. This whole event marked Suharto’s rise to power and the start of his New Order dictatorship.

- ↩ Hilmar Farid, “Indonesia’s Original Sin, 1965–66,” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 6, no. 1 (2005): 3–16; Malcolm Caldwell and Ernst Utrecht, Indonesia: An Alternative History (Sydney: Alternative Publishing Co-operative, 1979).

- ↩ Intan Suwandi, Value Chains: The New Economic Imperialism (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2019).

Comments are closed.