Also in this issue

Books by Tim Beal

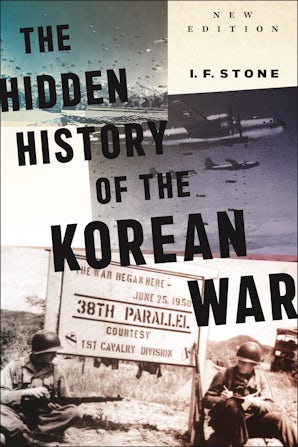

Hidden History of the Korean War

by I.F. Stone and I.F. Stone

Foreword by Gregory Elich, Tim Beal, Gregory Elich and Tim Beal