1981

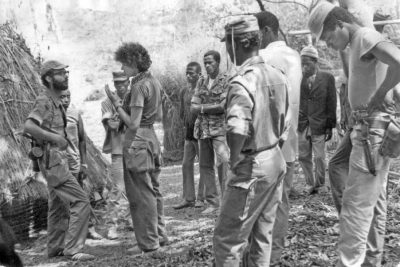

On January 30, 1981, just days after my return to the United States, South Africa launched its first major raid on Mozambique. Truckloads of South African commandos pushed seventy miles beyond the border, into Matola, a suburb of Maputo. They attacked three African National Congress safe houses, killing thirteen South Africans and a Portuguese national whom they mistook for Joe Slovo.

The attack was part of South Africa’s “total strategy,” aimed at destabilizing the whole southern African region. Botha was convinced, with reason, that the newly elected U.S. president, Ronald Reagan, and Britain’s prime minister, Maggie Thatcher, would provide political cover for South Africa on the global stage. Samora Machel’s response was a show of bravado and a demonstration of solidarity: “Que venham! Let them come!” he declared in a public speech a few days later. “Let all the racists come here, and then the great majority, the twenty-three million South Africans, can take power there! Let them come, and let the end of apartheid draw ever close! Let them come! And we’ll bring war to an end once and for all, for everyone!”

In October 1981, nine months after my precipitous departure, I arrived back to find a more vulnerable Mozambique. My treatment and recovery had overshadowed what was happening there, but I now felt the meaning of the attack with full force. In a strange way, the anger that consumed me made me feel closer to home.

During this visit, Lina Magaia blew into my life like a refreshing wind. Journalist, economist, determined activist, she became a trusted interpreter and informant, a friend who guided me through the changing political and economic climate. Lina was a few years younger than me, about my height at five-foot-eight or -nine inches, and a powerhouse of a woman, with an easy chuckle and a deep voice. Our friendship would continue for decades, both in Maputo and on her occasional visits to the United States. To her, I was African, a comrade from the continent. She provided a lens for viewing Mozambique and the workings of the revolution, and the destruction that South Africa wreaked on her country. My writing began to reflect this angle, focusing less on the role of women and more on the impact on women and children.

Lina was born in Maputo in 1945. Her father was a teacher; her mother was uneducated, from a rural family. Her father was determined that his children would get a good education. When Lina was ten years old, he was deemed sufficiently “civilized” to be granted the status and privileges of an assimilado. Lina transferred from a segregated mission school to one that catered to the children of settlers. As the only African in her class she was exposed to constant discrimination and denigration. In response, she challenged her teachers at every turn. “It was good training,” she said, chortling in a way that lit up her full round face. “It taught me to stand up for injustice, not only for myself. For the rights of my people.”

In 1961, when Lina was sixteen, Eduardo Mondlane visited Maputo. He was working for the United Nations in New York at the time, a post that enabled him to visit Africa. Unbeknown to the Portuguese administration, he was already involved in the formation of Frelimo. She absorbed all he had to say—his analysis of colonial oppression in Mozambique, his reference to the wave of independence sweeping through Africa. She began writing articles for publication, her first foray into journalism and into exposing injustice. It did not take her long to join a clandestine Frelimo cell, and in 1965 she decided to join the armed struggle based in Tanzania. As a precaution, she asked a friend to sew a hidden pocket into her handbag where she could hide the Frelimo documents she needed to enter Tanzania. But the secret police found out, and as she and her friend were saying their emotional good-byes they burst into her house and arrested her. With a nonchalant “Ciao!” her friend swung Lina’s bag over her shoulder and walked out the door. Without proof of her intent to join Frelimo, she got a relatively light three-month prison sentence. She was released with a warning: if she took part in politics, whether inside the country or out, her father would be arrested. She had little choice but to stay put.

A few years later, Lina was granted a scholarship to study economics in Portugal. In Lisbon, she was exposed to new ways of thinking about revolution and politics and was soon throwing herself into the underground anticolonial activism. Her studies suffered and she came close to losing her scholarship. Admonished by her father, she settled back into her studies, only to face a new challenge: she was pregnant. Abandoned by her Mozambican boyfriend, she dropped out of university to support her baby boy while continuing to direct her energies into the struggle.

Then came the coup in Portugal.

In April 1974, while I was listening to the newscasts in Guinea-Bissau, Lina was witnessing the events as they unfolded around her. After right-wing Portuguese fired into the house she shared with other Mozambicans, the movement sent her and her two-year-old son to Tanzania. There she enlisted in the Frelimo army and placed her son in the party’s child-care center several hours away from where she was based. But the toddler missed his mother, refused to eat, and was weakened by dysentery. He died in her arms.

“It was the Portuguese who killed my little boy,” she told me, still aching for her lost child six years later. “If it had not been for colonialism, for the need for the war, he would have survived.” She made a promise that she would never stop fighting for the children of Mozambique so they could have the life she could not give to her son.

“I will give my own life if necessary,” she said.

Meanwhile, negotiations between the new Portuguese government produced a ceasefire and handed over complete power to Frelimo in September 1974, and on June 25, 1975, the day Samora Machel was inaugurated as president of Mozambique, Lina marched into Maputo with the triumphant Frelimo army. She was home. There she met Carlos Laisse, her future husband and father of their four children. Lina was invaluable to me. She provided economic, political, and social context. Lina did not simply translate language; she translated culture. Soon after we started working together, we visited a small women’s agricultural cooperative, one of many that had been established in the zonas verdes, the green zones on the outskirts of Maputo, to encourage urban agriculture and generate a cash income. We were shown around by the co-op president. We saw poorly cultivated fields dependent on rains that had not come. We saw cages of undernourished rabbits, some showing signs of mange; a few perky ducklings wagging their tails as they waddled about; some skinny chickens scratching in the stony ground. After the tour, the twenty coop members gathered around us in a clearing. They sat in a semicircle on the ground, straight-legged and straight-backed, while Lina and I sat on squat wooden stools brought out for us. Some held babies on their laps, while a few young children played on the outskirts of our gathering.

At the edge of the group sat two local officials, also on stools, a man from the district Frelimo office and a woman from the local Organization of Mozambican Women (OMM) chapter. The man held a notebook and a pen on his lap. The women were quick to respond to Lina’s jokey manner with their own banter, providing an energy that was absent from the co-op itself. Needing no urging, they took turns to tell us about their lives under colonialism and how much better they fared after independence.

As they talked they expressed pride in their co-op, just two years old, where they each put in three days a week of work and then cultivated their own machambas on the remaining four days. They seemed undaunted by the poor harvests, which provided very little for them to divide up among them, let alone to sell. As I listened, one question kept coming into my head: What motivated these women to work with such commitment without tangible benefit? Lina turned to me, ready to translate my questions. I explained that I was stumped by this particular one, finding it hard to phrase in a way that would elicit more than pat answers. She grasped my problem instantly. “Tell me,” she said, looking around the circle and taking in each woman in turn, “if a man comes here tomorrow and says to you: ‘I will buy your cooperative and pay you a regular salary each week to continue working here,’ will you sell?”

There was a murmur of “no’s” and “nevers,” accompanied by vigorous shaking of heads. This is our cooperative, they responded. “Every day we see progress even if it is slow. You have just seen our new little ducklings. They will grow and bring us an income.” The united front was broken by one young co-op member. “I would definitely sell,” she said. “Why?” Lina asked. The woman stood up and looked directly at Lina, speaking in a strong voice.

“You’re pregnant,” she said. Lina’s newest pregnancy was just beginning to show. “You believe that the baby inside you will grow up healthy and look after you in your old age just as we hope our ducklings will. You don’t know, though, do you? As for me, I must feed my children. I must feed them now.”

The reaction from the two officials was immediate. The OMM cadre looked sternly at her. The Frelimo cadre, pencil poised, asked officiously, “What is your name?” The woman’s confidence crumpled. There was silence. All the women stared down into their laps, visibly perturbed. Lina was up in a flash. Clapping her hands and swinging her large, supple body she began to dance as she stretched out her hands and pulled one woman after another to her feet and led them in a rousing Frelimo dance and song. When the song ended, the women were laughing. The tension was released and the official had put his notebook away.

Toward the end of our visit, I randomly asked some of the women to tell me their names and offer details about their backgrounds. I avoided the “dissenter,” not wanting to embarrass her. Lina nudged me. “Ask her,” she said. “It is important that she and others understand that she can give her name without repercussions.” I did. This time no notebook was whipped out, I suspect because of Lina’s seniority, and when the women danced and smiled their good-byes as we started to leave, they were joined by the two officials, broadly smiling. Quintessential Lina.

1983

On this third visit, I already know the ropes. I walk briskly toward the airport building to be near the head of the inevitably slow line to change my dollars into meticais. Once again, I feel revitalized just being back. But I am immediately aware that something is missing. I look around, puzzled. Then I get it: the banner that greeted me on my last visit—the one reading bemvindo a uma zona libertada da humanidade—is gone. I am no longer being welcomed to the zone of liberated humanity.

Was the absence of the banner a signal that Mozambique, under growing pressure, wanted to be more accommodating, both to South Africa and to donors who might be scared off by the government’s socialist ideology? Was it aimed at the hope that the United States and Britain would rein in apartheid’s onslaught? Were they moving away from their socialist ideals? Probably a bit of each.

Not long after I deposit my bags at Judith’s apartment, I take a walk down the long, sloping hill to the baixa, the area near the docks, to make my habitual visit to the main Maputo market. I had discovered the energy of African marketplaces during my trip through Egypt and East Africa, and I have been drawn to them ever since. South Africa had no equivalent; segregation and control of movement of the African population had assured that. I like to breathe in the earthy smells of fruits and vegetables sold by women and look at the household goods and electronics sold by the men nearby. I stroll among the bustle of people as they fill their baskets and chat, catching up on local news and gossip, to the background noise of chickens and the general clattering sounds of a marketplace. I am not prepared for what I see. There is nothing there. Women sitting behind a cement platform that serves as their “store,” with nothing more than two bunches of parsley or a bunch of mint on display in front of them. Not even the greens that are a staple here. There is an inevitable bicha—a line—and I join it for eggplant, which costs about the same as it would in New York. The next day a friend happens on carrots, which run out quickly. There are rumors of lettuce and cabbage later this week but the bichas will be long.

What I see in the market is the ripple effect of the war. There is a severe shortage of fuel throughout the country. At the same time, drought has laid waste to much of the land. The South African onslaught makes it more difficult to ride out the disaster. The textile factories are producing 10 percent less than usual due to both the failure of the cotton harvest and the lack of transport. Cashew production, a critical export, has taken a beating, affecting foreign exchange. Stores are empty. Markets are bare. Peasant farmers who are able to cultivate are producing just enough to feed their own families: there’s no fuel to transport surplus crops to the cities. Villagers affected by drought and conflict desperately flee to the cities in the hope of finding food and shelter. They arrive at the doorsteps of relatives, who are expected, by custom stretching back through time, to provide for family in need.

Emma worked as an empregada (domestic worker) for my British friend, Teresa Smart. Emma’s ration card was hardly enough for three people, but now she had to stretch it to feed eight. “What can I do?” she asked Teresa, desperation in her voice. “There is a war going on. We can’t send them away!”

The answer for Emma was Operação Produção—Operation Production—launched in February 1983, a few months before my third visit to the country. The intent of the program was to relocate unemployed, nonproductive Maputo residents to the fertile north in order to alleviate the pressure on the city while at the same time helping to solve the farm labor shortage in Niassa, Tete, and Cabo Delgado. House-to-house checks began. Men and women who could not show that they were employed or failed to produce a Maputo resident’s card were deemed “nonproductive” and taken to processing centers. Women, many working at home in the informal sector, were particularly vulnerable to the often arbitrary decisions of officials. Within days they were flown north. At first the overburdened Maputo residents were relieved. Then doubt set in. An appeal process was instituted, but too late for those already relocated.

The stories of women scooped up in these raids were particularly poignant: women who worked in the home were being forcibly removed from their families; young women were accused of being prostitutes. Sometimes neighbors or family reported them just to settle a personal score. The parallels with the South African expulsions to the Bantustans were not lost on me.

I wanted to see for myself. Within a week of arriving in Maputo, I boarded a plane for Niassa with Teresa. The centers set up for the so-called inproductivos were out of bounds for us, but we were allowed to visit women who, we were told, were playing an active part in agricultural production on state farms and in communal villages. Teresa argued that we would be gathering such mundane, boring information that there was no need for anyone to accompany us. And so, with only a driver and a car we were sent tetherless to visit three sites, all within an hour’s drive of Lichinga, the capital of Niassa. Lussanhanda communal village was home to 276 families with well-tended vegetable gardens, a new school building, a health post and health worker, and a viable 250-member agricultural coop. Unango, a larger village the size of a small town, was a former Frelimo reeducation camp for people who had collaborated with the Portuguese. Matama was a state farm whose 2,000-strong workforce now included 600 inproductivos. The women we met told similar stories about being rounded up and arrested, taken to a detention center, and flown north within three or four days.

At Unango we interviewed four young women who were accused of being prostitutes. Two, Maria and Presilhina, aged twenty-two and nineteen, told us, their tone breezy, their smiles bright, that they did not want to return to Maputo. They had recently married local men. Ana, wiping away tears from time to time, told us how much she missed her companeiro, her common-law husband, who was in the army. We never learned the name of the fourth young woman who sat staring down at her lap, looking traumatized and never saying a word.

At Lussanhanda, we met a forty-four-year-old widow, Gloria, whose story echoed what I had been told in Maputo about personal vendettas. She lived with her son, a policeman, and her habitually unemployed nephew, whom she had raised from infancy. When the brigade came to get him, he was not home, so they took his wife. When Gloria took food to the young woman, she too was detained. “Until we find your nephew,” she was told. They found him. She was not released. Gloria shifted uncomfortably as she told her story. Then she looked down and finally said, in a soft voice, that the problem was the chief of her neighborhood block. He made it clear that he wanted to sleep with her. She refused. He became a predator. She continued to deny his advances. Now that he had some power, he had happily abused it. It was he who sent her away.

Our final visit was to Matama. We interviewed eight of the thirty women settled there. They had arrived with nothing more than the clothes on their backs, they told us, and no money. When they washed their clothes—without soap because they had none—they hid while they dried or pulled on their wet clothes. They slept in a shed with a leaking roof, covering themselves with discarded wheat sacks. But far worse, said their spokeswoman, Regina, was the authorities’ insistence that they marry male workers, who pestered them mercilessly and sometimes tried to use force. Some women had given in, but not this group of eight. Regina’s cheeks flushed as she sat in her faded, threadbare clothes, looking at us with pleading eyes, an expression mirrored in the eyes of the other women who sat with her.

“I keep the letters from my husband as proof that I am already married,” Regina told us. “It’s a long, long way back home. This is not a life.”

Back in Maputo we asked for a meeting with one of the government leaders who was in charge of Operação Produção. He was delighted with the program. “Already in this short space of time,” he said in fluent English, “culture and customs are being exchanged between the north and the south. Everyone is benefiting.” Perhaps noting the look of skepticism on my face, he continued: “With such a big relocation, of course, comes friction. Nonetheless, its negative impact is very small. It’s of little consequence.” Any mistakes, any missteps, had been corrected, he told us, estimating that maybe 2 percent of the inproductivos should not have been there. “We returned those,” he assured us. I glanced at Teresa. She was as flushed as I was.

“I wonder whether we shouldn’t regard women’s work as productive even if it is unpaid,” I suggested. He responded in a voice that brooked no patience with my naïveté. “I say to you, and I insist on this point, that it is more important to earn the meat to put in the pot than to just stand waiting for the meat to come to the pot. You take from the pot what you put into the pot.”

Meat? The average Maputo family seldom had the means to buy meat. Women worked hard, performing all manner of domestic labor to put food of any kind “into the pot.” I took a breath to calm my agitation. “It doesn’t take much to appreciate,” I ventured, “what can happen when thirty new women arrive among nineteen hundred men.” He agreed that this was indeed a serious problem. “It is easy for a group of these kinds of women to slip into prostitution under such circumstances,” he said. Teresa and I stared at each other aghast, for a moment completely speechless. One of us blurted out that some of the women we spoke to had common-law and even legal husbands. “Ah, they didn’t leave one husband,” he was quick to respond with a sneer in his voice. “They didn’t leave one boyfriend. They left several husbands and several boyfriends.” He drew out “several” for emphasis. “They are prostitutes.”

A week after our visit to Lichinga, Teresa and I drove to Gaza Province in the south to attend some of the several thousand meetings being convened throughout the country in preparation for the OMM Extraordinary Conference, to be held at the end of 1984. This proposed event had spawned something of a people’s social movement in the spirit of Frelimo’s mobilization in the liberated zones. People gathered in towns, villages, and bairros, in cooperatives, state farms, and factories; they held spontaneous discussions at bus stops, in shops, in marketplaces to debate the agenda, which included polygamy, lobolo, early marriage, adultery, initiation rites, divorce, prostitution, relations within the family, women in production, single motherhood. OMM wanted to know how both women and men regarded these practices, how they could be reformed. Reports from these meetings were analyzed and compiled into a document to be presented at the conference.

Teresa and I sat for hours listening to heated discussions. This was Mozambique and OMM at their best. Polygamy and lobolo aroused so much interest that additional meetings had to be convened for the other issues. Although women led the meetings, women in the audience had to be urged to contribute when the men monopolized the meetings. They expressed their feelings in other ways. At one village, an angry muttering buzzed whenever the men defended polygamy. “It is better to have more than one wife,” said one man. “When one of my wives goes to visit her family, then I can stay with the other wife. When one is ill, the other can cook for me. Without a second wife, I would suffer too much.” When the women’s murmurs crescendoed into jeering, local male leaders rushed around, gesticulating, shouting at the women to behave themselves. The protestations only quieted down when an older woman stood up. “I am the only wife of my husband. If I am sick, he cooks.” Loud prolonged applause. Occasionally a man denounced polygamy. “We no longer want more than one wife,” said a monogamous villager. “We must end this or a woman is nothing more than a capulana. You buy one today, another tomorrow. It cannot be like this any longer.”

We left Gaza, inspired by what we had heard, and by the process itself, once again feeling the promise of a new Mozambique. The conference held in November 1984 was something else. I would hear from cooperant friends that along with the positive energy it generated came disdain for women like those we had encountered on our visit to Lichinga. President Machel attended the full proceedings, constantly interjecting and dominating the discussions. Signe Arnfred, who worked with the OMM during this period and has written about gender in Mozambique, was appalled when Samora Machel jumped to his feet, cutting through the OMM general secretary’s report and pronouncing: “To be an unmarried mother is a disgrace! The concept, the very phenomenon, must be abolished.” This was too much for OMM, which normally followed the party line. The final conference document emphasized that unmarried mothers should be supported, not castigated.

What about the liberation of women as a “fundamental necessity for the revolution and a precondition for its victory”? Machel seems to have come a long way from that proclamation.

Having heard so many disturbing stories, particularly the ones connected to Operação Produção, I needed to work out what to do with them. I had first arrived in Mozambique to write about its progress through human-interest stories, through the stories of women. But now cracks had begun to appear in the beautiful façade that independence had constructed, and disappointment was seeping through them. A question insinuated itself: Was it worth it? For this?

One thing was clear: in Mozambique, where I watched the beginning of the country’s unraveling, it was South Africa that was pulling at the threads.

Comments are closed.