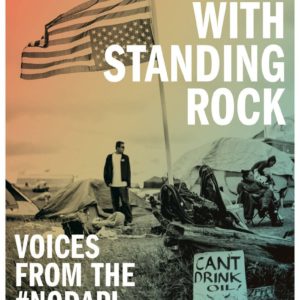

The story of the Indigenous movement to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) in 2016 and 2017 has been the subject of numerous articles and documentaries, many of which depict it mainly as an environmental and climate justice campaign to stop the pipeline from crossing the Mni Sose (Missouri River), just north of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota. Nick Estes and Jaskiran Dhillon’s edited collection Standing with Standing Rock: Voices from the #NoDAPL Movement tells a richer and more complex story of decolonization and indigenization from the frontlines.

The 1,172-mile pipeline cost $3.8 billion to construct, in order to pump 570,000 barrels a day of fracked Bakken shale oil. The Oyate (nation) of the Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires), also known as the Great Sioux Nation of the Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota-speaking peoples, led the opposition to what it called the Zuzeca Sapa (Black Snake), under the banner of Mni Wiconi (Water Is Life). The pipeline’s trespass of their historic territories was a violation of their treaties with the U.S. government, which under Article Six of the U.S. Constitution constitute the “Supreme Law of the Land.”

North Dakota agencies deployed many hundreds of police officers and National Guard units, brought in TigerSwan private security contractors from Iraq and Afghanistan, spent $38 million on security, and made eight hundred arrests. As a recent meme about Donald Trump’s deployment of federal agents in Oregon stated, “If you’re shocked by Portland, it’s because you weren’t paying attention to North Dakota.” Legal scholar Felix Cohen’s 1951 admonition has never been truer: assaults on Native American rights serve as a “miner’s canary” for the erosion of U.S. civil liberties.

The editors of the collection highlight that there was

nothing inevitable about DAPL. The most powerful state in the history of the world, with its military and police hand-in-hand with private security forces, waged a heavily armed, one-sided battle against some of the poorest people in North America to guarantee a pipeline’s trespass. That Water Protectors held out against the ritualistic brutality of tear gas, pepper spray, dog attacks, water cannons, disinformation campaigns, and twenty-four-hour surveillance is a pure miracle and testament to the powerful resolve of the Oceti Sakowin, Indigenous peoples, and their allies. Yet the wounds inflicted are long-lasting and descend from a longer history of colonial violence. (5)

The Water Protectors noticed, for example, that the DAPL guards’ infamous dog attack took place on the anniversary of a nearby 1863 massacre.

Nick Estes is Kul Wicasa (Lower Brule Sioux) from South Dakota, assistant professor of American Studies at the University of New Mexico, and cofounder of The Red Nation. He is author of Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock versus the Dakota Access Pipeline and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance, which can be read as a companion to this anthology. Jaskiran Dhillon is a first-generation anticolonial scholar and organizer who grew up on Treaty Six Cree Territory in Saskatchewan. She is a founding member of the New York City Stands with Standing Rock Collective, associate professor of global studies and anthropology at the New School, and author of Prairie Rising: Indigenous Youth, Decolonization, and the Politics of Intervention.

Their anthology’s “dispatches of radical political engagement” assembled a “multitude of voices of writers, thinkers, artists, and activists.… Through poetry and prose, essays, photography, interviews, and polemical interventions, the contributors, including leaders of the Standing Rock movement, reflect on Indigenous history and politics and on the movement’s significance.” As Tribal Historic Preservation Officer Ladonna Brave Bull Allard commented, “erasing our footprint from the world erases us as a people.… If we allow an oil company to dig through and destroy our histories, our ancestors, erasing our hearts and soul as a people, is that not genocide?” (17).

Followers of non-Native movements generally saw what they wanted at Standing Rock. Most environmentalists saw people of the land standing up to the fossil fuel industry to mitigate the climate crisis. Most liberals saw a racial “minority” standing for its right to clean water and religious freedom within the United States. Most socialists saw an oppressed community standing up to globalized corporate power. Most anarchists saw direct action activists standing up to a repressive state apparatus.

Standing Rock was indeed many of these things. But what these perspectives often overlook is the political struggle of Indigenous nations standing up to settler colonialism, a centuries-old, grounded struggle that does not fit as easily into an ideological box. Diné (Navajo) scholar Andrew Curley asserted that “to understand what happened at Standing Rock we need to amplify the critique that is muted in popular media and mainstream considerations, the critique of DAPL as a continuation of colonialism through its dispossession of Indigenous lands” (160).

Urban liberals and leftists alike have long marginalized Indigenous Americans as demographically small and geographically remote “asterisk peoples” within a “nation of immigrants” (320). They have often assumed that Native movements are fighting for racial “minority rights” or gaming profits, sidelining the core dimensions of political and territorial sovereignty, minimizing Indigenous cultural revitalization as mere “identity politics” or dismissing elders’ references to Mother Earth as simple “romanticism” of the past.

Standing Rock was for many the first meaningful exposure to a contemporary Indigenous struggle, which began to correct these failings. The collection offers a clear entry point for delving deeper into the political, legal, economic, cultural, and spiritual aspects of the movement. It highlights Standing Rock not simply as a mass protest, but as an expression of a longstanding national liberation movement against what historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz described as the “logical progression of modern colonialism” (93).

As the editors recall,

no one could have predicted the movement would spread like wildfire.… That’s how revolutionary moments, and movements within those moments, come about. Freedom and victory are never preordained. A new world at first inhabits the shell of the old. In a colonial context, it’s the old world that came before, an Indigenous world that never went away, that inhabits the imprisoning shell of the new world, waiting to break free. The dream that became one of the largest Indigenous uprisings in recent history had been nurtured and carefully brought into existence to save the water. (1)

#NoDAPL “was not a departure from so much as a continuation—a moment within a larger movement, but also a movement within a moment—of long traditions of Indigenous resistance deeply grounded in place and history” (2).

Dhillon asserts that “a fight for environmental justice must be framed, first and foremost, as a struggle for Indigenous sovereignty.… An accurate examination of the social and political causes of climate change requires a close look at the history of genocide, land dispossession, and concerted destruction of Indigenous societies and cultural practices that accompanies the irreversible damage wrought by environmental destruction” (235–36). The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe clearly condemned the racism of rerouting DAPL from the white-majority capital of Bismarck to the reservation’s northern border. But the #DAPL struggle went beyond the limits of the “environmental justice” framework into the deeper demand for #LandBack.

Curley notes that, despite the “ecological Indian trope,” Indigenous struggles are “not limited to environmental threats” (160). Sicangu Lakota educator Edward Valandra defines the Standing Rock movement as a “paradigm war” and a “watershed moment in human consciousness” that prioritized human relationships with the natural world (72). The editors maintain that “Water Protectors became criminal precisely because they were generating and upholding” natural laws, while also “reminding the United States of its own obligations to uphold its own treaties,” and point to “the practice of Wotakuye (kinship), a recognition of the place-based, decolonial practice of being in relation to the land and water” (2, 3).

A recurring theme in the anthology is that Standing Rock cannot be easily bounded in time. Diné human rights lawyer Michelle Cook notes that “occurrences like DAPL are part of a larger structure, not an event” (111). Coverage of the Standing Rock movement usually constricted its time span between the founding of the first Water Protector camp by Brave Bull Allard on April 1, 2016, and the military-style takeover of the camps by police and National Guard on February 23, 2017. According to mainstream media, the ultimate flow of oil through the pipeline marked the defeat of the movement.

The 328 days of Standing Rock straddled the Barack Obama administration, which would not rescue the Water Protectors, and the Trump administration, which could not fully defeat them. As the editors observe, “if there is a lesson to be learned from the historic movement…it is that great men don’t make history. Presidents at the helm of a white supremacist empire will not save us or the planet.… Nor do they, as individual men, doom our collective fate. The good people of the earth have always been the vanguards of history and radical social change” (4).

But the movement extended far beyond those 328 days, back to the Oceti Sakowin resistance against the Bozeman Trail and the Black Hills Gold Rush, and to the 1851 and 1868 Fort Laramie Treaties, the 1876 victory over George Armstrong Custer’s forces at Greasy Grass (Little Big Horn), and the 1890 massacre at Wounded Knee. Resistance continued into the twentieth century through tribal opposition to the 1950s megadam projects that flooded Missouri River reservations, and to the 1973 siege of Wounded Knee by federal agents deployed by Richard Nixon for seventy-one days (another precedent for Portland).

From the 1970s to the 2010s, a series of alliances among Lakota tribal members and white ranchers and farmers opposed coal and uranium mine projects, bombing and shooting ranges, coal trains, and the Keystone XL pipeline from the Alberta Tar Sands. I participated in the Black Hills Alliance and documented the series of Cowboy Indian Alliances in my book Unlikely Alliances: Native Nations and White Communities Join to Defend Rural Lands. Many of the Standing Rock organizers were veterans of these alliances and others grew up in them, bringing their vast experience to the struggle through lines of intergenerational continuity.

The Standing Rock movement also projected forward into 2020, as a federal judge finally upheld the Tribe’s case that the environmental review process had been inadequate, and even ordered DAPL’s flow of oil be halted (until the Trump administration’s appeal reversed the halt). DAPL had spilled about 277,000 gallons of oil by November 2017. Standing Rock has also resonated during the pandemic and Black Lives Matter movement as the Cheyenne River and Pine Ridge Tribes have used their sovereignty to set up protective COVID-19 checkpoints, tribal activists blockaded Trump’s ultranationalist speech at Mount Rushmore, and the statues of Christopher Columbus and other vicious colonizers have been toppled around the country.

Just as the Standing Rock movement cannot be bound in time, it cannot be bound in space. Dhillon notes how the events “defy purely localized analysis” and similarly challenge a purely globalized analysis that omits the richness of local struggles and actors. Political geographers study how movements can successfully “jump scales” between local, regional, national, and global realms, especially as they “think globally and act locally.”

The interconnectivity of the fossil fuel industry itself linked together activists in different parts of the continent, as they exposed the industry’s Achilles’ heel: shipping. The industry needed to ship fossil fuels from interior basins to coastal terminals, creating a “broader scramble to get North American oil to refineries, ports, and markets, and to build the transportation infrastructure that would make this possible” (224). Several of the book’s contributors map out this “many-headed hydra…of extraction and resistance” (354).

DAPL has shipped oil from one of these interior sources, the Bakken Oil Shale Basin, centered in western North Dakota, surrounding the Fort Berthold Reservation of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara tribes. Tribal youth organizer Zaysha Grinnell remembers:

As a young person I noticed the differences all around me due to this extraction process—in the environment, the lands, the people. I saw the lands that I had grown up on getting destroyed.… The people I grew up to love and care for were being sexually abused and sexually harassed on a daily basis. When these oil companies come in they bring in…the man camps and with that comes violence and sex trafficking. Indigenous women and girls near the camps are really affected by this, and we are not going to put up with it. (21)

The emergence of the militarized police state at Standing Rock and elsewhere in North America is being justified by the need to guard “critical infrastructure” from civilian dissidents redefined as “terrorists.” Trump has used an identical legal rationale to force meatpacking plants to reopen during the pandemic, inflicting the virus on their immigrant workers. Just as the state seeks to frame “critical infrastructure” as invincible, the corporations’ eel-like reach actually reveals Big Oil as vulnerable to coordinated opposition along its most important supply lines. Anti-pipeline movements have won court and regulatory decisions in 2020, not only against the DAPL, but also against the Atlantic Coast, Bayou Bridge, and Keystone XL pipelines.

The Standing Rock resistance birthed and rebirthed connections among peoples in concentric rings of solidarity. First, it enhanced solidarity among the diverse bands and tribes within the Oceti Sakowin nation, among its traditional leadership, tribal governments, and activist communities. As Kul Wicasa leader Lewis Grassrope notes in a fascinating interview with Estes, traditional leadership are heirs of the original treaty councils, women’s societies, and warrior societies that continue into the present. At Standing Rock, traditional hereditary leadership coordinated the cultural and spiritual direction, including daily ceremonies and prayer walks. The elected leaders of tribal governments (established by the United States in the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act) provided the political and legal strategies in the context of their sovereign nations’ relations with the federal government. Activist groups and camps provided direct action, media exposure, and corporate divestment campaigns that drew global attention. While these strategies were sometimes in tension, they operated on parallel tracks, especially as some who had grown up in traditional families had themselves become activists and elected officials, blurring the distinctions between what outsiders often view as separate “factions.”

The second ring of solidarity circled up other Indigenous nations, including at least 360 nations whose representatives visited Standing Rock camps, bringing their flags, songs, and dances. They had noticed the original run of Oceti Sakowin youth to Washington DC that set the movement into motion. They also brought their stories of struggle, from opposing oil and coal port terminals in the Pacific Northwest to opposing the Thirty Meter Telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawai’i and participating in the Idle No More movement that emerged in 2012 from First Nations in Canada.

The third ring of solidarity, what Peoria historian Elizabeth Ellis defines as “intersectional support,” was from non-Native justice movements, including Black movements against police violence in Ferguson and lead poisoning in Flint, Latinx and Indigenous movements against border walls being erected across occupied nations, and white and Asian allies and accomplices. As Grassrope recalls, “after a while, it didn’t matter what race or color you were. You were there to protect each other. That scared the shit out of the people on the other side! Because even they questioned their faith.… And some of them quit” (35). Indeed, some sheriff’s departments from around the United States, facing protests back home, actually pulled their deputies out of North Dakota.

The fourth ring of solidarity was international, as Standing Rock reverberated around the world, particularly among Indigenous nations such as Maori in Aotearoa New Zealand and Sámi in Scandinavia, but also among a range of communities fighting dams in Honduras and the Philippines, opposing oil wars against Iraq and Iran, and fighting settler colonialism in Palestine and Ireland. Standing Rock was one of the world’s first Facebook Live rebellions, streamed around the globe in real time and binding together many decolonial strands.

These concentric rings of solidarity all converged at Standing Rock, with the Water Protectors celebrating as cars, buses, and canoes arrived to join what became the state’s fourth-largest city. Lakota/Dakota “warrior woman” Marcella Gilbert described how “many tasks were shared between women and men, and camp needs were met on all levels.… Everyone became useful in ways that served the wellness of the camp community” (287). Shoshone-Paiute independent journalist Sarah Sunshine Manning observed that “for so many youth and adults alike, virtually every one of their basic needs was being met and, consequently, individuals were motivated, prompting them to offer up their best skills and talents for the good of the community. This was a community that each individual relied on, for food, shelter, safety, love, and belonging, and, conversely, the community relied on them too” (296).

While visiting Standing Rock in September 2016, I was struck most by how the camps felt like a liberated zone. The collaboration and resilience of the Water Protectors was obvious as they joined together to cook meals, cooperatively build temporary structures, and teach the kids in the camp school. In a microcosm, they prefigured a liberated Indigenous society, rooted in historic traditions of resistance and consensual self-governance. As Estes and Dhillon observe: “the movement reignited the fire of Indigenous liberation and reminded us that it is a fire that cannot be quelled. It provided, for a brief moment in time, a collective vision of what the future could be” (5).

Comments are closed.